Ulises Jiménez is wearing a shirt that was once white and denim pants worn down by time. His grey hairs droop over his face while he works on a piece of wood.

He meets us in a house that serves as an improvised workshop, in the district of La Mansion, in Nicoya, where he was born. “Before starting the interview, will you allow me to make coffee?” he asks in front of a kitchen with just one burner and one pot to heat water.

There are no luxuries nearby, except the sculptures and marble and wood molds resting all over the place.

Sitting around an old, wood table in the middle of the room, he tells me that he started to make art when he was a boy when he made his own toys with a machete.

It’s hard for Ulises to talk about his accomplishments and his success. Every time he mentions one, he interrupts himself with a ‘but’ as if not allowing himself to boast. But the truth is that he’s sold more than 600 pieces of art around the world.

He doesn’t make art in a conventional way, like you and I would imagine, like painting pictures or selling sculptors in stores or expositions. He makes pieces more than two meters that are on display in countries like China, Turkey and Argentina.

Maybe his humility now is due to what he learned and he lived through in more than six decades that preceded in our conversation.

***

He always knew that art was his thing, but he didn’t know what to study in order to develop his talents. An orientation adviser in La Mansión high school told him, “Ulises, you could become a great artist. Go to the vocation school in San Jose and study technical drawing.”

Technical drawing sounded nice because I was a farmer that had never heard anyone speak about that,” he says with a smile.

So he went to study in the Monseñor Sanabria high school in Desamparados and when he realized that drawing technique wasn’t artistic drawing, he almost cried. He was drawing blueprints, machines. He wasn’t making art. “It was dumb.”

He took a sip of coffee and said that he couldn’t do anything other than stay in the capital and finish studying. “My dad already paid. I told him that I didn’t want to continue and he got mad at me.”

He tried to study plastic arts in the Bellas Artes school at the at the University of Costa Rica, but it was a full time major and he “was just barely getting by.”

Once he enrolled, Ulises thinks that he could have been mates with Jorge Jiménez Deredia and ended up with him, with a scholarship in Italy. He says this calmly with an accepting tone rather than regret.

The comparison isn’t a small thing. Deredia is well known for, among other things, being the first Latin sculptor to have his work on display at the San Pedro basilica in Rome.

Meanwhile, Ulises combined his drawing classes in Guanacaste with his trips to the Autonomous University of Central America in San Jose where he finally studied plastic arts. A professor allowed him to take classes for free. He learned the basics of water colors and how to make molds for sculptures. He didn’t want to be a professor. He wanted to paint, sculpt and work for himself.

“In Costa Rica, a degree in plastic arts is only good for giving classes in a high school in a room with 40 students, 39 of which are goofing off and only one cares about art,” he says. The more classes he taught, the more frustrated he got.

He always knew that art was his thing, but he didn’t know what to study in order to develop his talents.

***

“So one day I grabbed my roll of pencils, my bag of paintings and a few pieces of fabric and I went to San Jose. I quit teaching and I started painting.” He was 29 at the time.

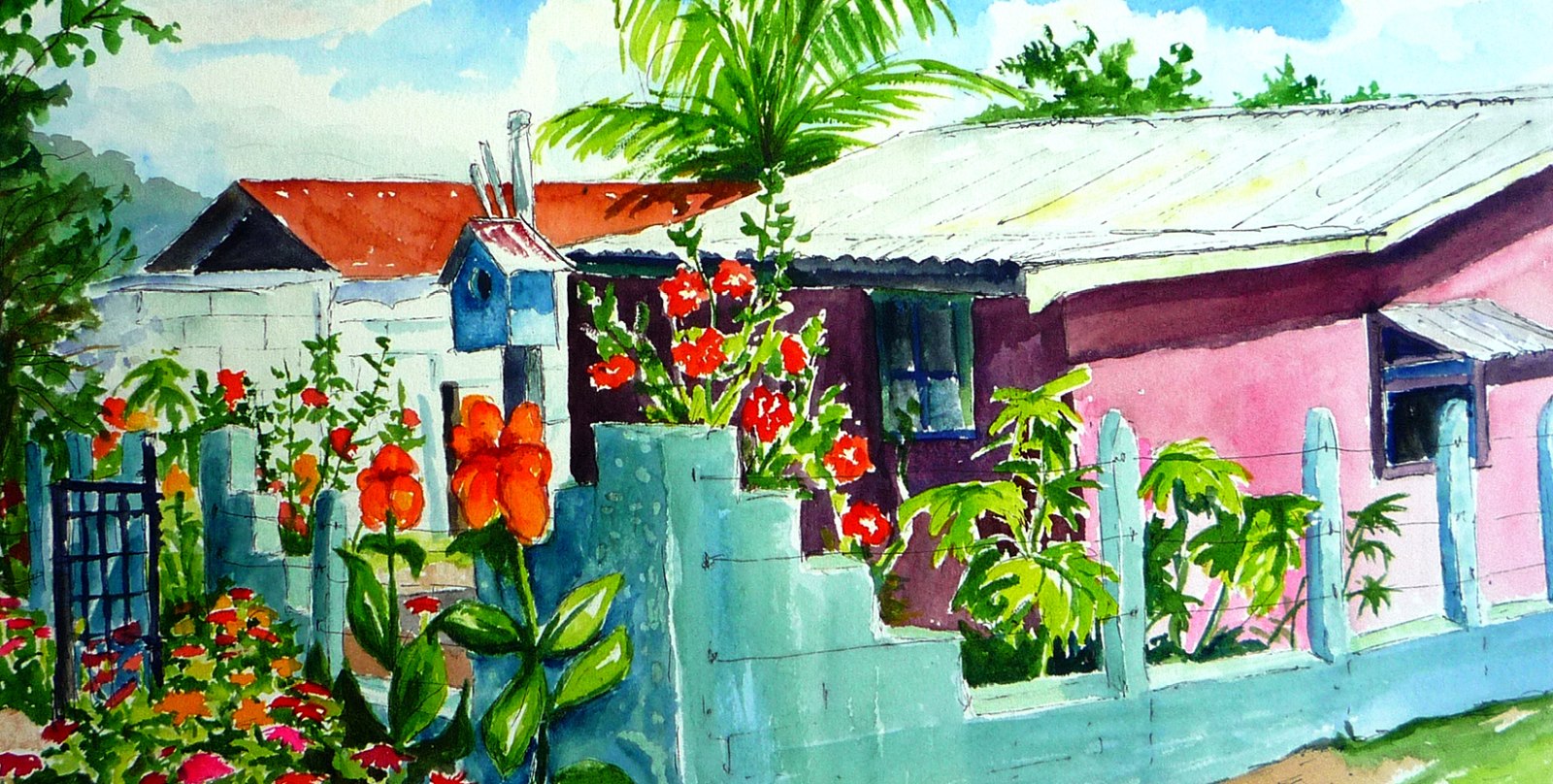

Ulises started with commercial painting. He painted flowers, houses and carts and sold them in the streets of San Jose, Heredia and Cartago.

During the process he discovered that sculpting paid more so wood became his favorite material. He started to perfect his technique and sell his work in hotels in Guanacaste and art fairs.

At age 55 (10 years ago) he got the opportunity that changed the way he made art.

***

Ulises’s wife, Xochitl Sierralta, says he doesn’t make friends, “friends come to him.” That’s how he met Gema Domínguez, a Spanish artist.

Domínguez organized a sculpture symposium in Tejeda in the canary islands. It was the first time that Ulises was invited to a symposium of this kind that required him to get on a plane and leave the country.

That was the beginning of 10 years of uninterrupted friendship between he and the Spaniard. A decade together to attend more than 35 different symposiums. In China, Egypt, Argentina, Tunisia, Russia, Turkey…

Symposiums are events that artists from all over the world apply to in order to go to another country and create art. They work and leave the sculpture to the organizers. Chosen artists have all their expenses paid and receive payment for their art.

In life, it may have occurred to me but there was no way I was going to leave Costa Rica with a work of art, making art, or to make a sculpture,” he says with his eyes full of excitement.

He called the work he did in Tejeda Timplista, a woman made of stone looking off to the horizon and playing guitar. It’s next to the history and traditions museum. It’s Ulises’s favorite work and that has all the characteristics that set his art apart.

“Some people have criticized me for always making the same face, but that face is my signature. My works aren’t geometric. There are straight lines, squares, rectangles and horizontal and vertical lines,” he explained pointing at one of his pieces in his workshop.

Xochitl says that those details make “you see one of his sculptures and say, ‘that’s Ulises.”

Ulises works with woods such as cedar and ash. He says he uses only recycled wood and that he has never cut a tree to make his art.

***

Sculpting took Ulises away from other talents, like writing. “I am convinced that you can’t do everything in this life. I think that if I were born again I would be a writer,” he says with a smile that paints wrinkles on his forehead and cheeks.

He has tried to write in his free time between sculptors. Some 15 years ago, he published a book with 22 stories called “Black Prism” and if he can find the time, he hopes to publish another one in the future with 30 new and corrected stories.

Like his sculptures, the inspiration comes from the land where he was born. They are stories about Guanacaste men and women and the folklore of the province.

“Guanacaste gives artists a lot of material. There is a lot of culture here and it’s authentic. The landscape, the livestock, the idiosyncrasies, It’s happy, festive. That gives you a lot of inspiration.

***

His mom warned him. Art wouldn’t earn him a lot of money, and reminded him when she saw him arrive in a broken down, 1986 pick-up truck. But, according to Ulises, what art gave him was the satisfaction that, sooner or later, he could live the life he wanted.

I believe that you don’t need a lot of money to live, and I get by with very little.”

In the future, he doesn’t see himself doing anything but painting, writing, or sculpting. Putting into practice what he learned in symposiums and, hopefully, organizing one in the province.

His wife Xóchitl sums up Ulises’s future best. “He will never stop making art. It’s like he was born to live and die from it.”

Comments