From Guatemala to Costa Rica in Central America, all countries celebrated the bicentennial of the independence. During this time, we see images of yellowed papers with manuscripts that are almost impossible to read, news about dates from a long time ago, phrases, reflections and paintings of people that we often don’t know how to recognize.

To clear up all our doubts, we spoke with philologist and genealogist Mauricio Melendez, and we distanced ourselves a little from what happened in Cartago 200 years ago so that he could explain to us what was happening then in the province that we now know as Guanacaste. But first we have to answer another question.

What was the Party of Nicoya?

It was a political-administrative unit during the Spanish colonial period that existed from 1787 to 1824.

It was separated from the Province of Nicaragua by the La Flor River, which is located about 30 kilometers (about 19 miles) north of La Cruz, and separated from the Province of Costa Rica by the Tempisque River.

It arose from what was previously called the Alcaldía Mayor de Nicoya (Greater Mayor’s Office of Nicoya). The Party of Nicoya was a smaller government that depended financially but not politically on the Intendance of Leon, in Nicaragua. It had a lot of independence, even to make political decisions about the region.

The Provincial Council of Guatemala declared independence from Spain on September 15, 1821 and sent this notice to Leon.

There, the Provincial Council of Nicaragua and Costa Rica made the decision to also declare independence from the Spanish government.

This council— which included Nicoya— had seven representatives: four from Nicaragua, two from Costa Rica and one from Nicoya: Colonel Joaquin de Arechabal.

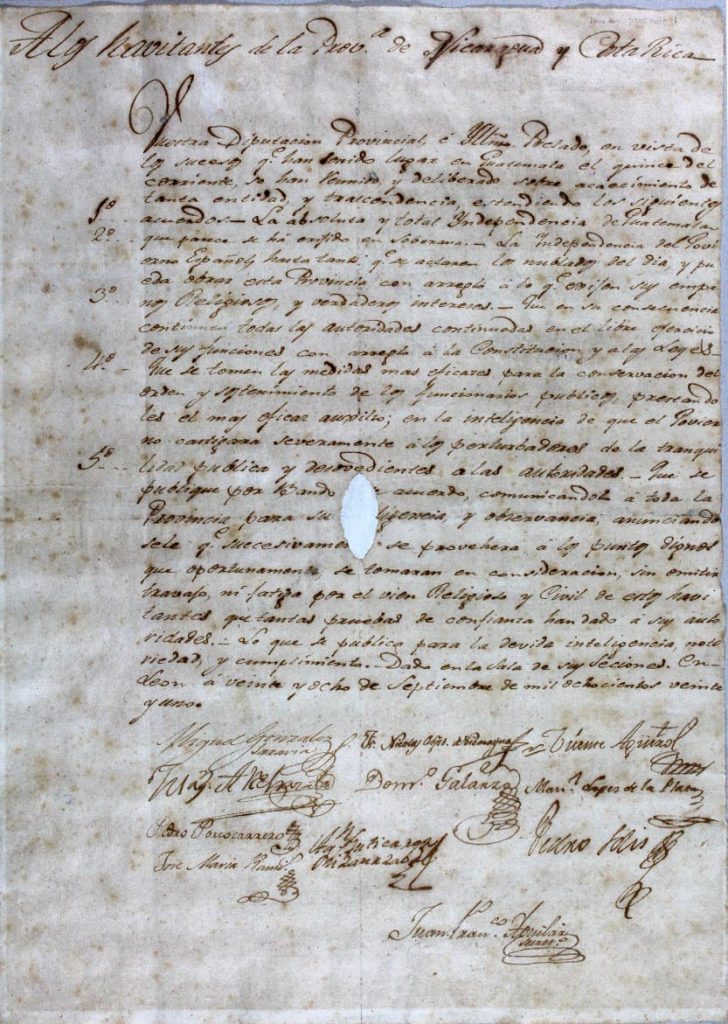

The independence of the Party of Nicoya happened at the same time as that of Costa Rica and the rest of the Central American countries: on September 28, 1821, when the Acta de los Nublados (Cloudy Act) was signed.

Acta de los Nublados.

Who inhabited the area in 1821?

Melendez is also the president of the Costa Rican Academy of Genealogical Sciences and he worked on the academy’s publication of a journal called “The Origin of the Guanacastecans: the Viales Family and the Signers of the Annexation Act,” which explains who our ancestors were.

This investigation reviewed 2,792 baptisms in Nicoya from 1783 to 1804 and determined that 73.5% of the people baptized were mulattos (although they are cited that way in the documents, this word was used to refer to the zambos: a person of mixed indigenous and black ancestry), 20% were Amerindian, 1.1% Spanish, 0.3% mestizo and 2.5% had no category, in other words, the priest didn’t indicate a socio-racial categorization for them.

How did our black ancestors arrive and what happened before 1783?

It’s hard to know for sure. In 1767, there was a big fire in Nicoya’s town hall and all the documentation was burned. Only six years later, there was another fire in the old convent, where all of the sacramental documents of Nicoya were: baptismal certificates, marriage certificates, marriage records, trials that had to do with the Church, etc.

If Nicoya was conquered by the Spanish in 1524, those two fires in Nicoya left an information gap of more than 200 years.

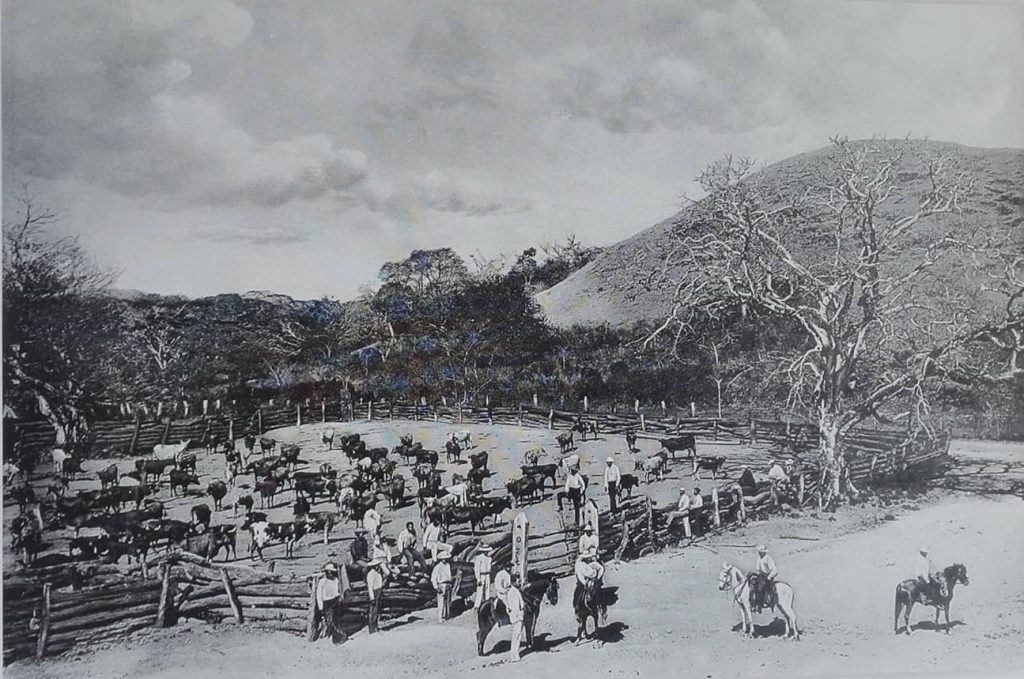

What we do know is that the mulattoes that settled around Nicoya began to establish small cattle ranches, and by the end of 1700, they were already competing with those of Rivas, Nicaragua, in numbers of cattle.

Corral El Viejo, Guanacaste. Cortesy: Mauricio Meléndez

Who were some of the most powerful families?

The oldest record is from the family of Miguel Viales and Victoria Moraga. They were married in 1741, approximately, and are almost always referred to as Afro-mestizos and mulattos.

This family became very powerful in the Nicoya region, as powerful as those of Rivas. There were families from Rivas who had haciendas in Guanacaste but only came during some seasons and left their servants in charge of them.

Since they were in the Nicoyan territory, the Viales began to gain power and make decisions about the region.

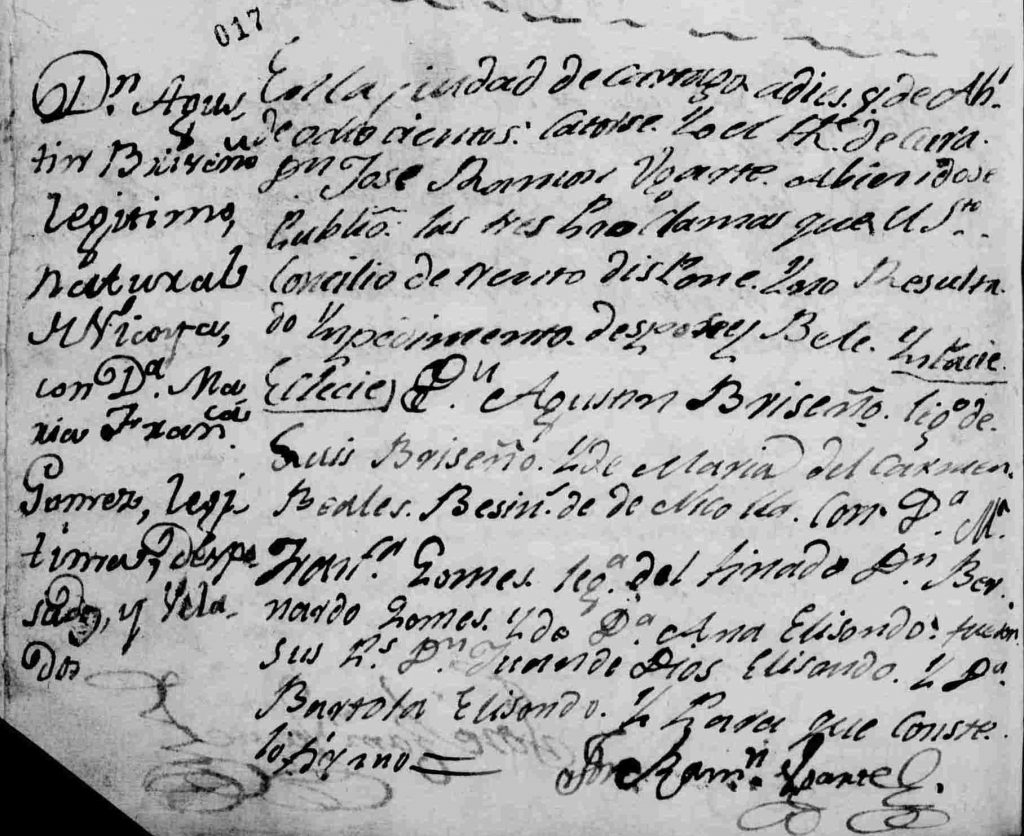

Another important family was the Briceño family. There are records of some Briceño brothers who came from Rivas and married the Viales sisters around 1750.

Agustín Briceño and Francisca Gómez marriage certificate. Cortesy: Mauricio Meléndez

In the time before independence, members of families such as the Viales and the Briceños were already referred to as “don,” which was a category of nobility (the lowest rank of nobility).

They were called that because of the power they had acquired, possibly because of their appearance and because of purchasing clothing that was typical of the Spanish. Thus began the social ascent that later was firmed up with the annexation of Nicoya to Costa Rica, a decision that didn’t make everyone happy.

How was the Party of Nicoya’s relationship with Nicaragua and Costa Rica?

A large portion of Nicaragua always thought that Nicoya was part of their territory due to a genealogical matter. In colonial times, this place was inhabited by families who came from many places, but mainly from Rivas.

Liberia, which was called Guanacaste at that time, was home to a large number of Afro-mestizos from Nicaragua, who worked at the haciendas owned by families from Rivas.

Although there was no “brotherhood” between the population of Nicoya and Costa Rica, the people of Nicoya did consider Costa Rica to be more stable than Nicaragua, which at that time was going through long, violent civil wars.

From Nicoya, they observed that instability with attention. That’s why one of the things that the Party of Nicoya requested from Costa Rica in the annexation act that was signed in 1824 was military support, since they only had “26 useless rifles to defend themselves.”

The Act of Annexation of the Party of Nicoya to Costa Rica is a document signed on July 25, 1824. Archivo Nacional de Costa Rica.

Another point that they took into consideration to join Costa Rica was trade. Puntarenas was much closer than the port of Corinto, in northern Nicaragua.

The Party of Nicoya asked for an “immediate and reciprocal participation in the benefits and advancements that are palpable in Costa Rica,” because Nicoya was a region that was very overlooked since colonial times. This is another reason why they sought to be annexed to Costa Rica: the “state of destitution in which the Party’s towns [found] themselves.”

There are people who say that the annexation of the Party of Nicoya is the product of a family decision. Others, like doctor of history Victor Hugo Acuña, explain it as a process of political forces. This is how he explains it in his review of the book Nicoya: Its colonial past and its annexation or addition to Costa Rica:

“The annexation can’t be understood as a simple matter decided by the inhabitants of the former Party of Nicoya, since it was a process in which the federal authorities and the states that disputed that territory intervened.”

Comments