Latin American Idol was on the television. Costa Rican participant María José Castillo was singing “Sobreviviré” by Mónica Naranjo. It was the last concert before the big finale and she was the first Costa Rican participant to get that far. The entire country was watching, including the nursing staff that was working that night at La Anexión Hospital in Nicoya.

That’s what Margoth Rojas remembers of that October 8, 2008. That day she gave birth to her first daughter. She remembers being dilated to three centimeters. They tried, but she didn’t feel she was ready to deliver. She wasn’t having contractions. There were still two more days until the date that doctors told her she would give birth.

She says that she was standing and leaning against the wall with her hands, because in that position the pain wasn’t as intense. She asked the nurses who were watching the program to help her walk, sit, anything. But they didn’t help her. They induced the delivery with “saline solution.” They never explained why. For her, it was the start of a very long night.

In that moment, Margoth felt that the way they were treating her wasn’t correct because they made her feel bad. As time passed, she realized that she had suffered obstetric violence, but she couldn’t call it that until years later.

Obstetric violence is a term used to describe the disrespect that pregnant women suffer before, during or after delivery. It consists of, for example, not being able to choose which position to give birth in, or medical staff not informing them about procedures, or even insults and screaming. It’s a dehumanizing, humiliating treatment.

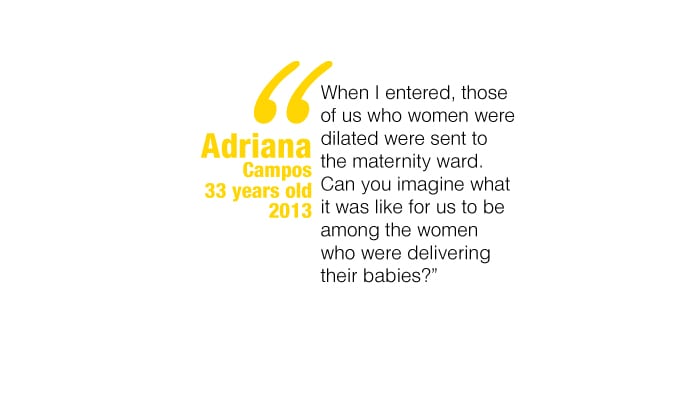

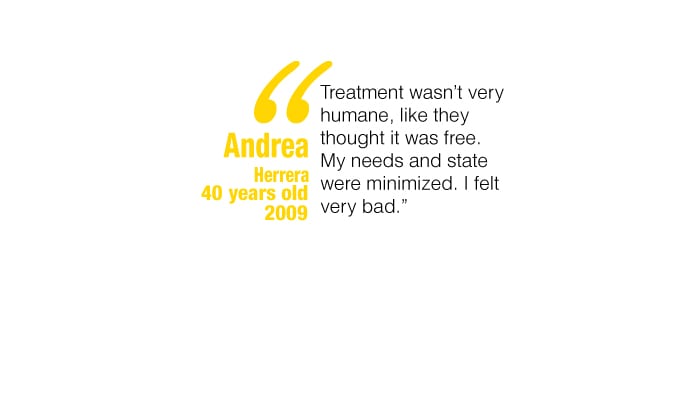

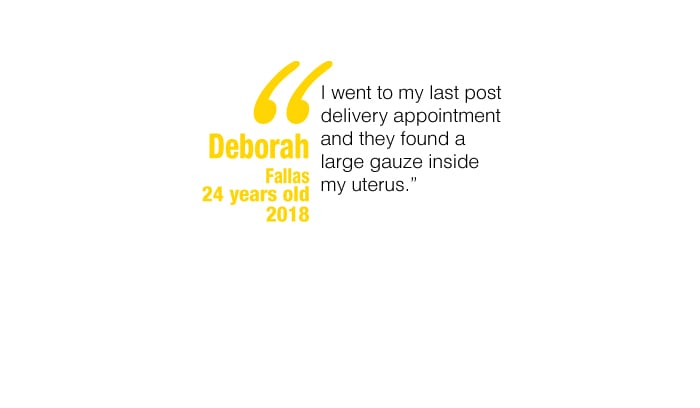

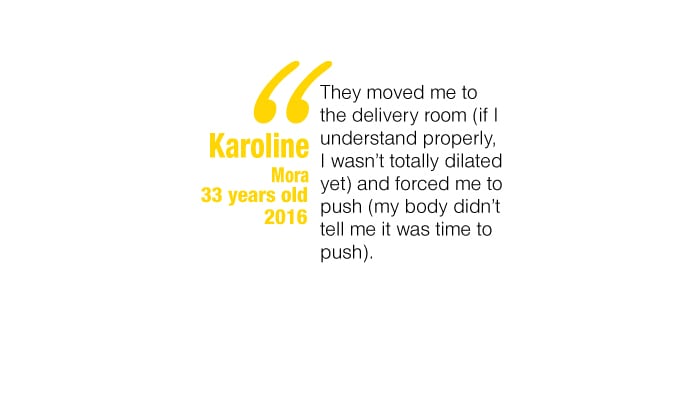

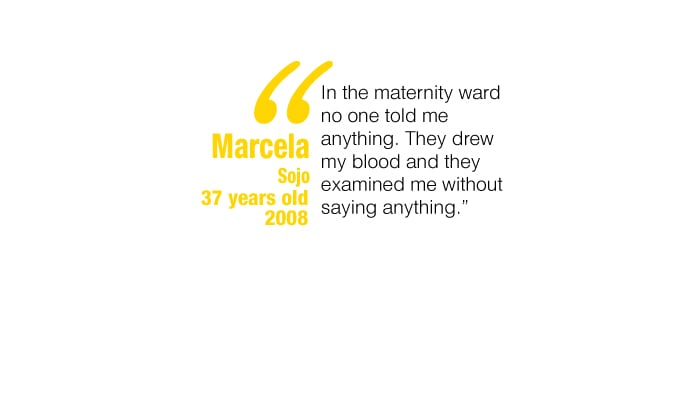

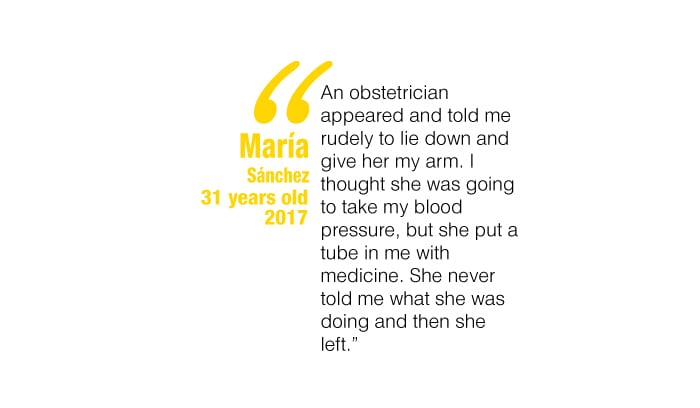

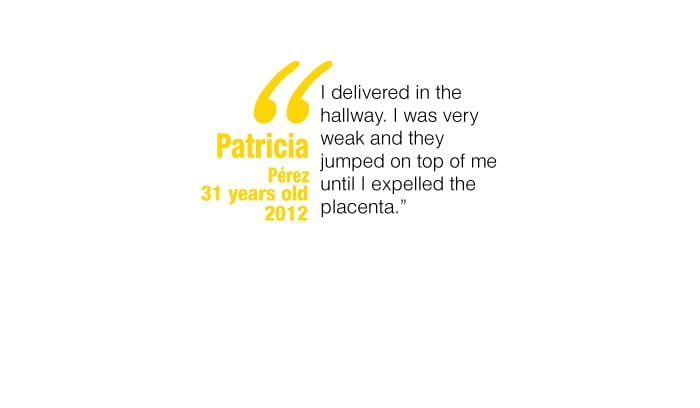

When we asked women on our social media websites to tell us about their delivery experiences, we received 20 testimonies from across the country in just two days. They all said that they felt violated at some point during their pregnancy.

Academics and international legislation defines obstetric violence as any act or conduct that causes a woman harm or physical or psychological suffering during and after giving birth. It constitutes a violation of human rights at the hands of medical personnel in the country’s public and private health centers.

It also includes prenatal classes at Costa Rica’s public clinic’s called EBAIS (see graph).

Larissa Arroyo, attorney and specialist in human rights, explains that “violence against women has progressively come to be recognized, and now there are a lot of terms and many types of violence that people have recently been made aware of.”

That which is named, exists. When I see people talking about obstetric violence I say, ‘I lived through that and didn’t know it was violence,’” Arroyo said. “It becomes a prevention mechanism so it doesn’t keep happening.

Anner Angulo, Director of La Anexión Hospital in Nicoya, where Margoth finally gave birth, says that things have changed. The obstetrics and gynecology department was moved in 2016 to a new medical wing in a modern building with better infrastructure. According to Angulo, the medical staff is committed to respecting the rights of women carrying children. He says that the hospital hasn’t received a single report for violence during childbirth and that there is no open administrative investigation into the department.

But, 10 years ago, Margoth ended up with muscle tears. She lost consciousness. She opened her eyes and someone’s elbows were on her stomach. She closed them. Then opened them again and heard the words “you have to keep pushing.” She woke up in intensive care.

How Many More?

Margoth’s case isn’t exclusive to the La Anexión Hospital in Guanacaste nor to any specific period of time, but it is a problem that affects women in the province. Sill, the state doesn’t have any specific data on how many women have been affected or how long this has been going on.

Gabriela Arguedas, researcher at the University of Costa Rica’s Center for Women’s Studies and Research (CIEM) who has studied the topic since 2013, was emphatic that in Costa Rica, not even the Social Security Institute (CCSS) nor any other state institution collects data on obstetric violence that would allow the country to determine the scope of the problem in Guanacaste or any other part of the country.

In her opinion, the lack of official data doesn’t mean that the problem doesn’t exist. According to Arguedas, there is sufficient qualitative, anecdotal evidence from women that allows for validating the problem across the country.

The Office of the Ombudsman has denounced the lack of data for at least three years.

“It’s urgent for the state to have updated data on the events of violence and the attention provided (by health centers) to women and for this information to be made public,” said a complaint filed by the Ombudsman in October 2016.

A year before, in 2015, the Office of the Ombudsman confirmed in a report that some hospitals in the country violated the rights of women during and after birth. The report details several reports filed by affected women with the Ombudsman.

A year before, in 2015, the Office of the Ombudsman confirmed in a report that some hospitals in the country violated the rights of women during and after birth. The report details several reports filed by affected women with the Ombudsman.

“I say that I’m feeling very bad, I complain and they say that everyone goes through this, that I shouldn’t be a pansy,” says one testimony in the report. The Office of the Ombudsman requested that the name of the victim remain anonymous.

The document takes into consideration the services provided at the Enrique Baltodano Hospital in LIberia. At the time, the institution reported that women who were being transferred to Liberia to give birth didn’t have guaranteed transportation to return to where they came from.

That same year, the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL) and CIEM presented the topic of obstetric violence before the Inter-American Human Rights Commission in Costa Rica. During the hearing, the state admitted that they received 1,248 complaints from January 2015 to August 2015 related to obstetrics in the nation’s hospitals, but they couldn’t verify how many of those referred specifically to obstetric violence.

In response to the lack of data, Arguedas is working on a research project that aims to create the first Obstetric Violence Observatory in the country, a space that seeks to raise awareness about the problem, orient women and produce information.

“We need to produce data and contribute to the development of theory and public policy,” the researcher said. “We want to make recommendations for state institutions about what actions are needed to confront this problem.”

The Voice of Guanacaste has requested an interview with a spokesperson from the CCSS since September 6 about this issue. This newspaper also requested the data used by the institution to measure this type of violence, whether directly or indirectly. We didn’t receive a response by the time this edition went to print

Real Rights

Margoth always knew that she wasn’t the first woman to go through this. As the years passed, she realized that her experience in 2008 wouldn’t be the last.

In 2016, during her ninth month of pregnancy, her mother took her to the emergency room at the Nicoya Hospital because of bleeding. They admitted her and a doctor told her “in an hour and a half we are going to come and perform a dilation and curettage (a surgical procedure that can provoke an abortion).

Margoth recalls responding “you haven’t told me what I have. No one has come to examine me.”

The doctor replied, “Why the tantrum?”

This time, Margoth was no longer a first-time mother. She wasn’t as afraid. She knew that she at least had the right to hear an explanation as to what was happening with her pregnancy and what the procedure was for.

The Previda Foundation, which gives childbirth preparatory classes across the country, conducted a survey of 1,114 women cared for at 12 hospitals in the country between 2013 and 2014. Only 40 percent of those surveyed said that medical staff requested their consent about procedures they were going to perform.

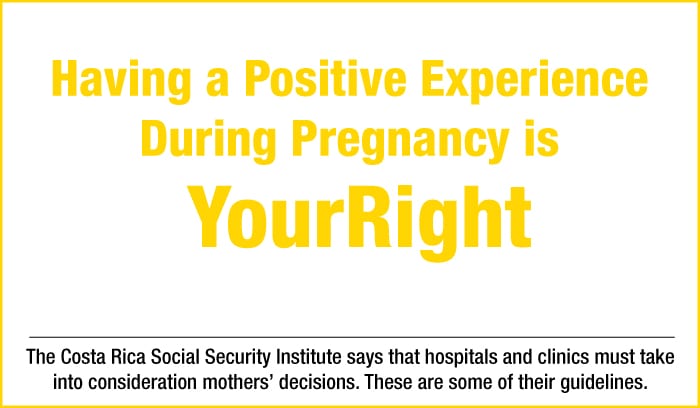

Without knowing, Margoth was demanding a right that all pregnant women have in the country and which are defined in large part by the CCSS. Even if the institution doesn’t explicitly use the concept of obstetric violence, it does define how to provide respectful attention to a mother.

The information in the “Comprehensive Guide to Attention to Women and Children in Prenatal Stage, Delivery and Post-Delivery” published by the CCSS since 2009 is an example of that documentation. (See graph “Have a Positive Experience…”

“The CCSS doesn’t mention obstetric violence, but it does clearly define the rights of the woman during pregnancy,” said Rebeca Turekky from the non-profit association Mamasol, which advocates for more humanized deliveries free of violence across the country. “What needs to be done is demanding that these protocols are complied with.”

“The CCSS doesn’t mention obstetric violence, but it does clearly define the rights of the woman during pregnancy,” said Rebeca Turekky from the non-profit association Mamasol, which advocates for more humanized deliveries free of violence across the country. “What needs to be done is demanding that these protocols are complied with.”

There are other instruments in addition to the guide such as the General Health Law and the Law of Rights and Duties of CCSS Users. There are other guidelines from international organizations that the country considers binding, such as those issued by the Inter-American Human Rights Court.

After hours of insisting on exams and explanations on why they needed to perform the dilation and curettage, Margoth was allowed to leave. A new doctor gave her the option of going home at her own risk. She was told to rest and take some medications. Her son was finally born at Hospital Mexico.

“I almost lost my child, but I put my foot down,” Margoth says clearly. “I just wanted them to explain things to me,” she said as if it happened yesterday.

By Law

In Costa Rica, there is no law that defines or penalizes obstetric violence. For some specialists, the problem needs to be recognized. Arroyo is one of them.

“Because it’s a newly recognized type of violence, we haven’t yet been able to put it in a law,” Arroyo said. “Many times it’s considered malpractice, but that’s not enough because that’s not necessarily going to have a gender element or a human rights element,” the lawyer said.

The Ombudsman’s Office has been emphatic in at least two reports that no instrument contains mechanisms for women to report that they feel violated nor establishes sanctions for medical personnel that doesn’t comply with what the CCSS guide.

For researcher Gabriela Arguedas, a new legal norm won’t necessarily solve the problem.

What’s lacking is real commitment from the authorities to recognize this problem,” she said.

In Latin America, there are specific laws against obstetric violence in Venezuela (2007), Argentina (2009) and Mexico (2014). Venezuela, for example, was the first country in the world to create a law regarding the issue.

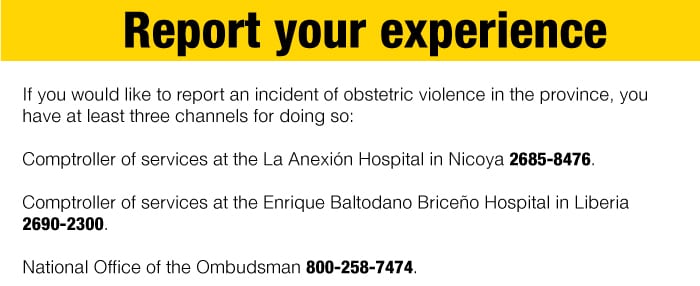

In fact, Margoth says that she wanted to file a complaint for each of her pregnancies, but she didn’t. During her daughter’s birth, for example, the file (of which The Voice of Guanacaste has a copy) wasn’t correctly filled out and omitted the name of the staff member that attended to her. She didn’t know who to file the complaint against.

A Less Bitter Birth

Not all stories are like Margoth’s. There may be fewer and fewer. What is true is that there are signs that indicate that awareness of the problem in the country’s health centers has grown.

In February 2017, the Costa Rica Social Security Institute (CCSS) announced that it was introducing music, fragrances and popsicles to hydrate the mother during birth in the country’s maternity wards. They are also allowing a trusted partner to accompany the mother before, during and after delivery.

According to Rebeca Turekky from Mamasol, the CCSS has taken a step toward talking about a more humanized childbirth or respected childbirth, a concept considered the antithesis of some of the components that feed obstetric violence.

The La Anexión Hospital in Nicoya is one of the centers that adopted some of these measures.

Director Anner Angulo said that moving to a new medical wing in 2016 helped to provide attention with a greater focus on the wellbeing of the pregnant woman since they now have the infrastructure to do so.

Now we have curtains to provide privacy for patients when we are going to examine them,” Angulo said.

According to the Ombudsman, in 2017 the CCSS committed to investing more than ¢972 million ($1.7m) in order to strengthen maternity wards in the country and make some physical upgrades.

Gloria Espinoza, the head nurse for La Anexion’s obstetrics and gynecology department added that another change they made at the medical center was training staff, including doctors and nurses, about better practices in providing care during delivery.

“We went to get to know the experience in Puntarenas [Hospital Monseñor Sanabria], which is one of the pioneering health centers in this process,” Espinoza said. “We went and we saw what they were innovating and we came back and adapted it to our conditions.”

For the head of nursing, the true strengthening of La Anexión has been the mystique with which the staff works.

“Raising awareness around humanized childbirth has motivated the staff,” she said. “Obstetric nurses, by their own initiative, make cards where they put the baby’s footprint and they give it to the mother. We have aromatherapy and that was also donated by the nurses, by the staff.”

Turekky says that, in addition to these improvements, medical staff need to be taught these things in the classroom and the population and women need to be educated about their own bodies so that it is clear to them that they are ones who should make decisions about it.

Comments