A project that aims to update Costa Rica’s old water-related legislation is tangled in a legislative labyrinth and will not pass during this administration, leaving Guanacaste in regulatory limbo regarding areas such as illegal water extraction and pollution.

Authorities agree that there is much work to be done in order to have updated legislation.

“I do not think it will be approved in this administration. We’ll have to see if a future legislature will take it up. I hope so,” said Yamileth Astorga, executive president of the Costa Rican Institute of Aqueducts and Sewers (in Spanish, AyA).

The project began as a popular initiative seventeen years ago as an effort to change the current law, which dates to 1942. Today there is another project in its place as the original initiative overran its statue of limitations.

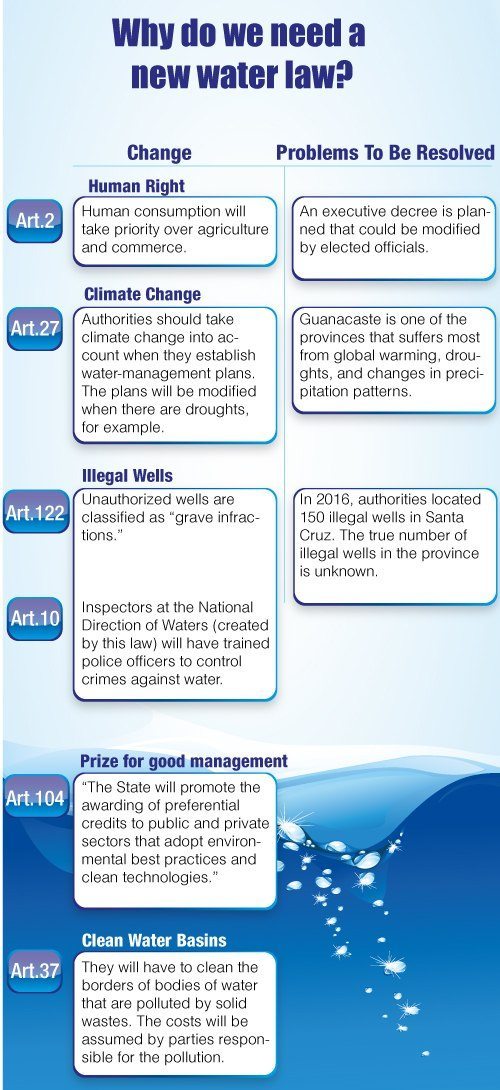

The problem with the current, 1942-era rules is that they do not offer tools to the AyA or the Ministry of Environment and Energy (MINAE) so that they might sanction crimes against water resources. Punishments currently are a “slap on the wrist,” said Fernando Mora, vice minister of Aguas y Mares.

Agricultural Sector Says No

Sources agree that the National Chamber of Agriculture and Agro-industry has been the project’s main detractor. And they accept that: “As the law stands, we’re going to after them hard,” said Juan Rafael Lizano, president of the chamber.

Although Lizano recognizes that the new project is better than the popular initiative, the chamber has already put together sixteen observations against the document for legislators to review.

According to his position, the law affects farmers and calls them “the responsible party for everything wrong with water.”

The AyA’s executive president has said in previous interviews that agricultural irrigation is highly inefficient.

“Seventy-five percent of water consumed in this country, and also in Guanacaste, that is extracted from aquifers is used for irrigation,” said Astorga.

Farmers state that an example of how the law affects them is the punishment for diffused pollution, established in article 122 of the project, which calls for a sanction of up to seven base salaries. However, farmers say that what is considered “diffused” pollution has no clear definition.

The chamber’s executive director, Martín Calderón, explained that contamination could appear near a property without the owner having been responsible. “So why would we sanction that person?” Calderón asked.

Sixteen other questions have the project stuck in the Legislative Assembly’s Environmental Commission, which will likely table the issue, instead leaving it for the next commission.

Comments