When professor Rodolfo Núñez arrived in the folkloric city of Santa Cruz more than 20 years ago, he noticed that Santa Cruzans often used the phrase: “Next, as Curly would say.”

The expression was used when they called the next in line. Curious, he asked one day where the phrase came from and it was explained to him that that’s how they immortalized one of the old sex workers from Santa Cruz.

They called her Curly (“La Colocha”). And it wasn’t only her sayings that were seared in the memory and language of this Guanacastecan canton, but her physical traits as well.

Some older gentlemen that sit in the Santa Cruz park everyday, in front of the main entrance to the Catholic church, remember very well what this woman who they met in the 1960s and 70s looked like: white skin, brightly-colored eyes, blonde, curly hair and very elegant.

“She was like Marilyn Monroe,” a Santa Cruz resident whose last name is Herrera tells me as she recalls, together with her sister-in-law, the names of sex workers.

Curly used to work in El Chucu Chucu, an old and well known dance club that used to be in downtown Santa Cruz that had rooms where she and other women performed “the world’s oldest profession.”

Why are they remembered? Because Santa Cruzans have immortalized these women in their oral history.

The memory that Santa Cruzans have of Curly and her colleagues made Rodolfo Núñez, professor at the National University (UNA) in Nicoya and coordinator of the Guanacastequidad Program at the Public Education Ministry, and late Costa Rican historian Juan José Marín, interested in studying why the people of Santa Cruz remembered sex workers in such a special way.

“More than remember, people create a historic memory and it would seem that the prostitutes are part of the construction of the Santa Cruz identity,” Núñez explains to me at UNA’s library.

His colleague Marín had already done studies on prostitution in Costa Rica, but they considered there was a lack of information describing this work in rural cities far away from the Costa Rican capital.

Neither the researchers nor local residents neglect the fact that sex work often comes along with social problems, like poverty.

In Costa Rica, this work isn’t recognized with the social guarantees that other jobs have. There is also no census of how many people do this kind of work, but Nubia Ordóñez, president of the sex workers association La Sala located in San Jose, says that there are many more than there were 30 or 40 years ago.

“There is a countless number of us,” the sex work activist adds, and later explains that they continue to be stigmatized which is why many women work anonymously and in clandestine places.

The Study of Memories

According to the findings of the research, in which they interviewed local residents and studied the oral history about them, Santa Cruz has incorporated sex workers into their collective local imagination, which has made them remember the girls with affection.

They remember their nicknames: Juana Pectral, The Milonga, One-armed Chepa, Bald Lilly, Maria the Tuscan, Three Hairs. And they remember the places where they worked: El Chucu-Chucu, Malagueña, Mil Amores and the Calabazo.

They even remember some anecdotes, like the one that Curly only had a bed of boards in her room and when they would ask her, “Why don’t you buy a mattress?” she responded, “why don’t you bring knee pads?”

In some songs such as El Chucu Chucu by Los de la Bajura (a very well known band in Guanacaste), Curly is mentioned.

I asked Curly if She wanted to dance

And she responded with tremendous reality

Come here my dear and I will make you wiggle

To the sound of the music I’ll make you sweat

The same song makes reference to La Toscana, another one of the women that used to work in the dance club.

She’s sliding her way over, she’s sliding her way over

The bandit La Toscana has the urge to dance

Balo Gómez, member of the band Los de la Bajura and a local folklorist, tells me with some suspicion that these songs his group sings don’t refer to prostitution, but they mention them because remembering these women is part of the culture that surrounds any town: an oral tradition.

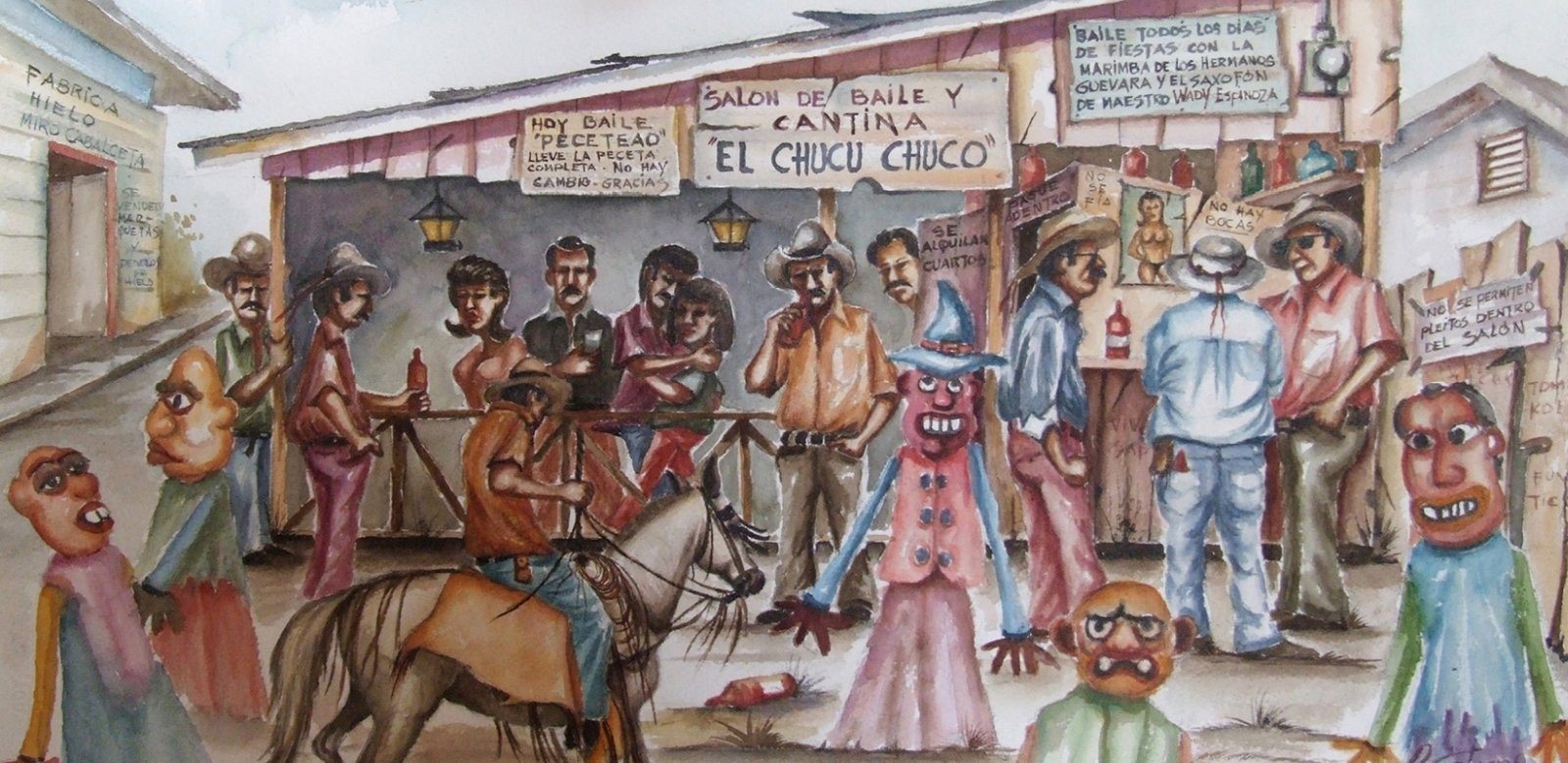

One of the paintings by Santa Cruz artist Freddy Gatgens also depicts El Chucu Chucu. In it, you can see the dynamic under which this iconic place functioned. Besides being the spot where people met to dance, it was also the venue to consummate other types of relations.

A Cultural and Social Phenomenon

In their research Núñez and Hernández explain that, parallel to the January festivities celebrating Saint Christopher of Esquipulas with dancing and typical activities, sexual work also played a major role.

In the Santa Cruz park, Celina Alvarez, another retired teacher, assures me that they remember them and that these women weren’t seen in a contemptuous way, but as part of the town’s celebrities.

“It’s part of our idiosyncrasies as Santa Cruzans, but not with that term (prostitutes),” Alvarez says, as if trying to remove the social weight that the term carries along with it.

Santa Cruz isn’t the only town where there was or is prostitution, nor is it the only town that remembers the girls or the places where they worked, but its memory and oral tradition and history is probably what has made these women immortalized in such a peculiar way in the canton.

“I have read a lot about Santa Cruz and normally it talks a lot about the cultural aspects, the Christ of Esquipulas, the food, the dancing, the music,” the professor says, and adds that other social spaces like the cantinas or brothels, which also speak to a town’s identity, aren’t studied.

The walls of this Guanacastecan canton reflect the traditions that, year after year, Santa Cruzans bring to their cobblestone streets. These walls and streets are witness to other stories that, hidden in the memories of its people, also constitute the Santa Cruz identity.

Comments