Between the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, the Tempisque River remained the main artery connecting the Central Valley with Guanacaste. Vessels navigated its waters, transporting goods and people in a constant back-and-forth between Guanacaste and Puntarenas.

At that time, the only land route between the province and the Central Region was the “Camino del Arreo,” a trail that started in Esparza and extended to Nicaragua, but which became impassable due to the heavy rains during the rainy season. Thus, the imposing Tempisque River was the most viable and safest option for transportation.

And for this back-and-forth travel, the communities of Bebedero and Porozal in Cañas enjoyed the unique advantages of their privileged location: they had two important ports to reach the Guanacaste heights.

Porozal, with its Níspero port adjacent to the Tempisque River, and Bebedero with the Bebedero port, located on the tributary of the river with the same name and that flows into the Tempisque. The communities are located next to each other but differ greatly in how they connect to the center of Cañas. Bebedero is only 15 kilometers from the central district of the canton. To reach Porozal, however, one must travel 47 kilometers in the direction of the La Amistad bridge.

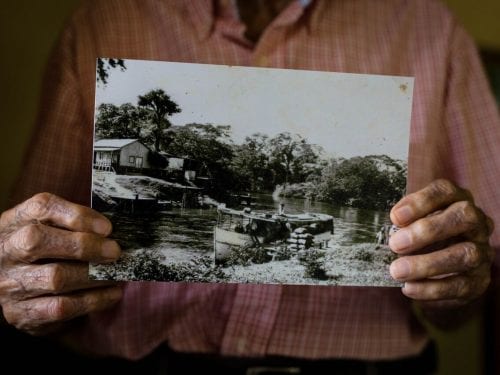

Traveling agents, livestock, all the trade and merchandise arrived there. The inhabitants of Cañas, Tilarán, Bagaces, and even Upala traveled via the river,” recalls Walter Porras, a 98-year-old Cañas resident who witnessed those good years in his youth.

But from that opulence in Porozal and Bebedero, nothing remains but memories, and today both are going through a different story, one marked by neglect.

Walter Porras in his house in the center of the canton of Cañas.Photo: Rubén F. Román

Two districts along the banks of the Tempisque River

Walter frequently visited the community of Bebedero in the late 1940s. His brother and father lived there, and his work also took him to the area.

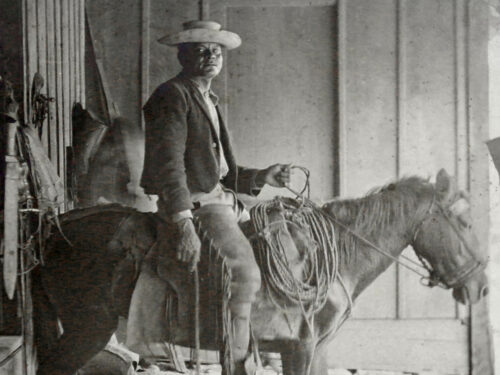

“I started working on the construction of the Inter-American Highway. I had the privilege of going to receive many North Americans who came to clear the path. So, I would ride on horseback with three or four pullen beasts to meet them at Bebedero port,” Walter recounts.

He remembers there were few houses in Bebedero, but a lot of activity. His mother owned the Hotel Cañas in the center of the canton, where they hosted people coming or going from the docks.

And the peak was similar in Porozal, with its Níspero port.

The people from the highlands would come to Porozal to catch the boat and cross the entire Gulf of Nicoya to bring all the goods that weren’t available at that time. It was something very important,” recalls Melvin Carrillo, a Nicoyan who arrived in Porozal over 40 years ago.

In both districts, agriculture, livestock, and fishing also thrived, but no commercial engine compared to their ports.

With progress came abandonment.

Ironically, for the communities, “progress” brought neglect.

The construction of the Inter-American Highway in the 1940s marked the beginning of the end of an era for Níspero port and Bebedero port.

With the new land access, traditional trade routes through the river began to decline, affecting both traders and port workers.

This era came to an end with the construction of the La Amistad Bridge in 2003.

“People have had to migrate because opportunities are very few,” Melvin explains.

Nowadays, the economy of both towns depends on very different activities. In Bebedero, the main source of employment comes from Ingenio Taboga, while in Porozal, its factories like Pinturas Sur.

The decline in the economy is reflected in the state of their ports. Both port infrastructures lie in ruins. The absence of investment and maintenance has led to progressive deterioration.

In both districts, some families depend on fishing for their livelihood.Photo: Rubén F. Román

An idea

In the book “Cañas Cálida Tierra” from 2003, José Fabián Solano describes the journey through Bebedero port as a fascinating experience. During the trip, travelers can observe a wide variety of birds, ducks, crocodiles, and iguanas enjoying the morning sun. Landscapes that still endure despite the passage of time.

“Bebedero has untapped potential,” Walter comments. “The beauty of its mouth at the Gulf of Nicoya is a treasure for tourists.”

Melvin, for his part, sees similarities in Porozal. “We have enormous tourism potential. With our rich fishing and diversity of wildlife in the impressive wetlands,” he is convinced.

Both residents of Cañas agree that roads have contributed to improving connectivity in the country. However, they also recognize the need to leverage the proximity to the Tempisque River to promote tourism development and improve the quality of life for residents.

“Why, if the people and these two districts contributed so much to the development not only of Cañas, but of Guanacaste, why are we going to abandon them in such a criminal way as we are doing?” concludes Carlos Vega, president of the Municipal Council of Cañas, echoing the sentiments of his fellow residents.

According to Vega, tourism that focuses on history and culture is one of the most effective strategies to revitalize areas with a rich historical heritage. He wants to bet on that.

On June 10th, the Municipal Council of the canton approved the draft bill titled “Bill for the Declaration of District of Historical Value and Public Interest for Tourism Development in the Districts of Porozal and Bebedero, Canton of Cañas.”

The text sent to the Guanacaste Commission in the Legislative Assembly aims for the government to undertake public works and development projects in both communities, to preserve historical heritage and promote tourism development.

Níspero port.Photo: Rubén F. Román

“When the roads and La Amistad Bridge arrived, there was no compensation for the communities of Porozal and Bebedero. Simply put, their main development was river transport. Suddenly, we took away their major source of income at that time and abandoned them,” he adds.

Although the current document does not mention specific measures to ensure that these benefits materialize effectively, for Vega, this is just the beginning.

What we aim for is that the legislators do a good job reviewing and including the economic aspect that we didn’t address in the law,” he concludes.

Beyond the ruins of their ports, the memories of Walter, Melvin, and other protagonists of the history of both districts, remain the hope that with proper attention and government commitment, they can write a new chapter in their history—one that honors their past while looking more optimistically towards the future.

Comments