We see his figure painted in oils riding across the murals of our towns or dancing with leg gaiters and a leather cloth or cape in some traditional dance performances. Packages of rice at the grocery store and even the comic book series of a national vigilante are named after him.

The sabanero (the cowboy or plainsman) is a symbol of the province, the protagonist of regional culture. The livestock hacienda (ranch) is where he displays all of his courage and knowledge. But Guanacaste changed its way of producing. The old haciendas gave way to hotels, and where there were once extensive pastures, sugarcane and rice now grow.

Although it’s very difficult to find him in Guanacaste’s plains now, this character is still very much alive within the cultural imagination. How did the sabanero come to have so much prestige, and what were the reasons why his trade has almost become extinct?

The Rise of the Savannah’s Horseman

Before talking about the sabanero, we have to understand the setting in which he emerged: the cattle ranches, called haciendas. Soledad Hernandez, a historian and author of the book Tope de toros de Liberia: Resignificaciones históricas (Liberia’s Bull Parade: Historical Resignifications), explains that the Spanish introduced cattle between the 16th and 17th centuries.

In the first phase, they used these cattle to transport goods during the conquest and later to extract fodder and leather. It wasn’t until a couple of centuries later that haciendas began to be established throughout Guanacaste to market or sell live cattle, either for fattening or to be slaughtered and consumed.

Many of these cattle were wild; in other words, they reproduced and were raised between the vegetation of the hills and the savanna. The worker who had to go out to herd and move the cattle scattered across the enormous Guanacaste savannahs to incorporate them into the hacienda’s herd was precisely the sabanero.

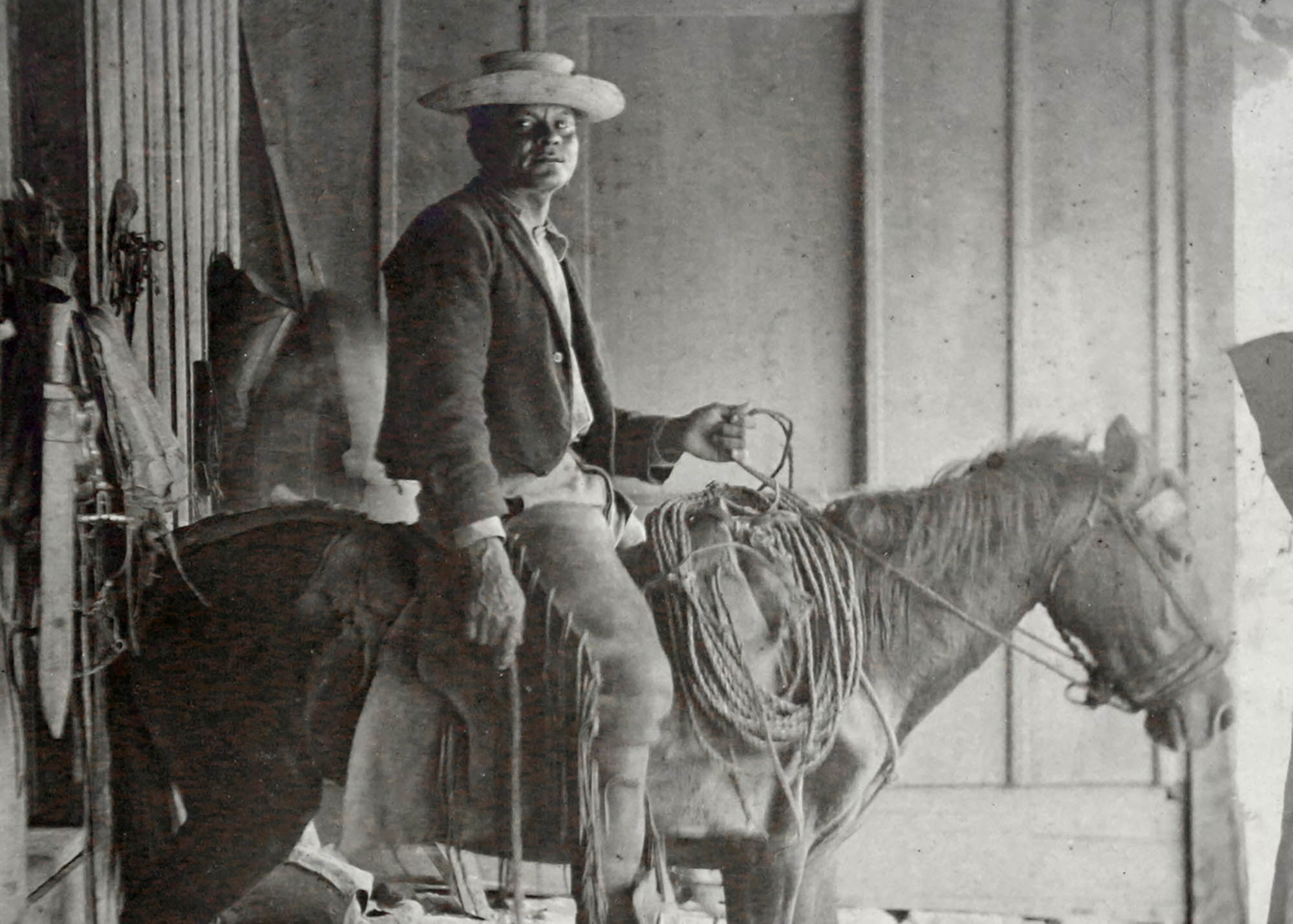

“The man of the savannahs was the one who skillfully moved around the plains and mountains, an expert lassoer, distracting bulls with a leather cape, a distinguished rider, driving cattle along endless and lonely roads,” Hernández describes in her book.

During his long work days, which began very early, he also treated the animals’ wounds, looked after the births of calves, sometimes patrolled the property and worked with horsehair to produce cruppers, girths, bridles and other products.

The sabaneros enjoyed a lot of trust and worked without much supervision from the landowners, who generally lived in Rivas, Nicaragua, or in the Central Valley and visited their haciendas sporadically. Labor was very scarce in the province, which forced the owners to pay good salaries to the sabaneros at the end of the 19th century.

In his book Vida cotidiana, trabajo, juego y fiesta en la hacienda ganadera guanacasteca (Everyday Life, Work, Play and Festivity on the Guanacaste Cattle Ranch), David Díaz explains that during that era, there was a great contrast between the conditions of the coffee growing world of the Central Valley and that of the ranches. The sabanero worked with much more freedom and greater pay. “The salary on the Guanacaste haciendas came to be higher than that of workers on the Central Plateau (between 0.75 and two colones per day in the first case and between 0.50 and 1.28 in the second),” he describes.

Sabanero de Hacienda Catalina photographed in 1904 by José Fidel Tristán.Photo: Archivo Nacional de Costa Rica

All the knowledge of the sabaneros was nourished by the daily activities inside the haciendas, but it was later transferred from that private area to the public.

This happened in religious festivities such as the one for the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, which gave way to what we know today as the Tope de Toros de Liberia (Liberia’s bull parade); or the festivities in honor of the Black Christ of Esquipilas, during which the Typical National Fiestas of Santa Cruz take place.

During these activities, the sabaneros showed off all their knowledge passed on through generations.

The sabanero gradually became an iconic figure in Guanacaste, a figure that gained great regional prestige over time,” explains Hernández. That prestige would turn him into an emblem of the province.

The Symbol of Guanacaste

The sabanero made its way into the social imagination down to this day, not only in Guanacaste, with a museum dedicated to the sabanero in Liberia, but also at the national level. Law 8394 of 2003 assigned the sabanero his own day every November 10th “as a recognition of the character who modeled the Guanacastecan person.”

People who have investigated the root of that “Guanacastecan person” as an icon have found his origin a century earlier, when Guanacaste newspapers and local elites began to feed the idea of a homogeneous regional identity.

In a research paper titled “Guanacaste: el surgimiento de un discurso regionalista” (Guanacaste: The emergence of a regionalist discourse), Soili Buska, professor at the School of History of the University of Costa Rica (UCR), explains how they achieved it.

Those who championed this homogeneity were mainly intellectuals who had the opportunity to go to the Central Valley to study or represent the province on a political level. They perceived Guanacaste as a region that was homogeneous in its cultural, social and economic characteristics, distinct from the rest of national society.

And it was up to the Guanacastecans, as sons and daughters of that region, to defend those ‘regional’ interests before the national State,” explains Buska.

The sabanero was precisely a symbol of that regionalist and homogenizing discourse, according to Esteban Barboza, a researcher at the National University (UNA). “He has always been important as a symbol of local vindication in the face of all the talk that came from the Central Valley,” explains Barboza.

Paradoxically, it is the politicians from the center of the country who, searching for an identity, took all those symbols that existed from the cattle ranch and institutionalized them as national folklore: the sabanero, music, dance, and other cultural manifestations.

By the time Sabanero Day was declared, that character and the haciendas had experienced their glory days many decades before, since they no longer represented the main source of wealth in the province.

From Haciendas to All-Inclusive Resorts

The sabanero began to see how his plains were changing little by little into sugarcane and rice plantations. The construction of roads opened the way for using trucks and they were no longer needed to make those legendary cattle drives from Guanacaste to Puntarenas and Alajuela.

Cattle ranches began to break up or turn into hotels and restaurants in response to the tourism model that was beginning to appear on the horizon. Wages worsened and greater supervision of hacienda administrators ended the freedom with which they previously carried out their tasks.

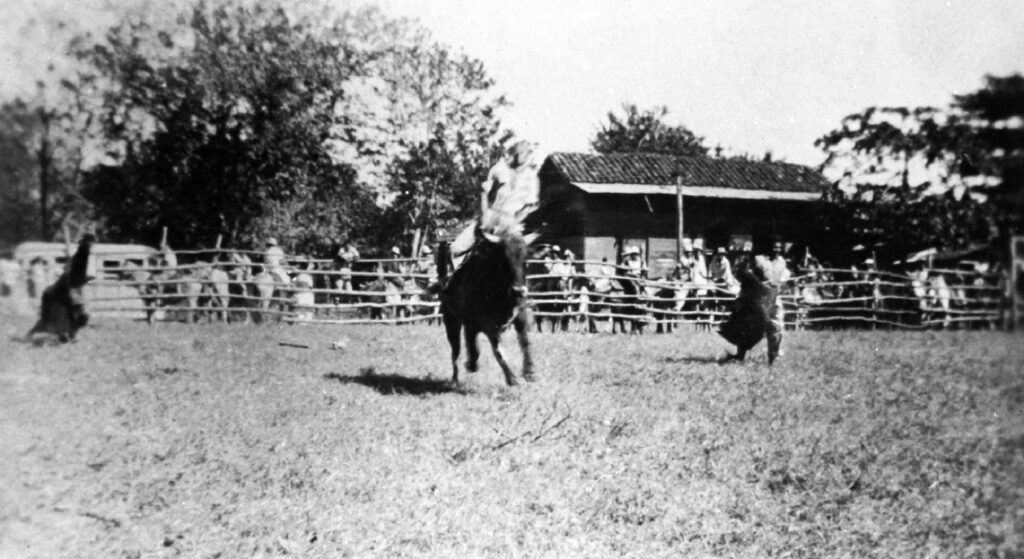

José Cisneros, famous sabanero of Santa Cruz in 1964.Photo: Archivo Nacional de Costa Rica

According to researcher Soledad Hernández, the decline of the haciendas caused very marked unemployment in Guanacaste and especially in the cantons in the north of the province, such as Liberia, where the haciendas had been an essential element in hiring labor.

“It was a very hard time because people didn’t know how to do anything else but that. That had been his job throughout his life, that of his parents, that of his grandparents. Many people were left adrift, not only without work, but also without any social guarantee. Most of the sabaneros of the 70s went home without a pension after having given all their youth to the hacienda,” explains Hernández.

With the fall of the haciendas, no other choice remained but to reinvent themselves. In a research project, the dean of the Chorotega Region National University, Victor Baltodano, classifies the sabaneros into four types:

- Traditional sabanero: those who worked with livestock all their lives on a salaried basis on Guanacaste’s large haciendas.

- Sabaneros in tourism: those who moved towards tourist activity and the younger sabaneros, who combine hacienda work with work in tourism.

- Transformed sabaneros: those who combine the work of sabaneros with that of farm laborer and have changed their work practices.

- Sabaneros by appropriation: those who have never worked as sabaneros or who do so part-time.

Baltodano states that “what the sabanero does is no longer so relevant but rather what he can represent. He becomes part of the tourist package and this changes the way he behaves and interacts.”

Those tourist packages to which he refers are the ones that several hotels in the province offer with “the possibility of being sabaneros for a day.”

According to Esteban Barboza, the possibility of peering into the province’s idealized past hides the exploitation that the sabanero has suffered since colonial times and conceals the gigantic social and territorial inequality that the hacienda created.

We’re not questioning the unjust possession of land, the slavery of laborers, a lot of things that even persist structurally in Guanacaste to this day,” he adds.

On this topic, Soledad Hernández points out that there is sufficient information to confirm that the enslaved population of African descent was fundamental in consolidating the haciendas of the 17th and 18th centuries in Guanacaste.

At El Viejo [Hacienda], slaves were bought and sold during the time of the brotherhood. That means that the haciendas of that time, we’re talking about the 18th century, had black labor,” she specified.

The colonialism of the first centuries of conquest did not end with independence and with the annexation, explains the researcher. The hacienda perpetuated inequality in opportunities and in social advancement.

“You don’t see that there was a socialization of the wealth and opportunities that the hacienda presented. The heirs and owners of haciendas have been the ones who have had the opportunity to go to study abroad and who today have very favorable economic conditions,” she emphasizes.

Although the golden age of the sabanero has passed, his knowledge and culture is alive: the fiesta, the riding, the saddlery. The researcher attributes this to the rebellion of that character who confronts his unequal historical reality and still becomes the protagonist of the fiesta.

Her book, she explains, is a tribute to the people who are still bearers of that tradition.

“To the people who are still resisting modernity and this ideological and manipulative use of the history of Guanacaste. People who are consistent with their ideology, with their life, with what they learned, [and who] are still there, struggling tremendously within the territories so that the culture that they have considered valuable remains alive,” she highlights.

Comments