One day, Deilyn heard that her father hadn’t sent her to school because she didn’t have “the papers.” She says it was about four years ago, when she and her younger sister moved from Nicaragua to Costa Rica after her mother’s death.

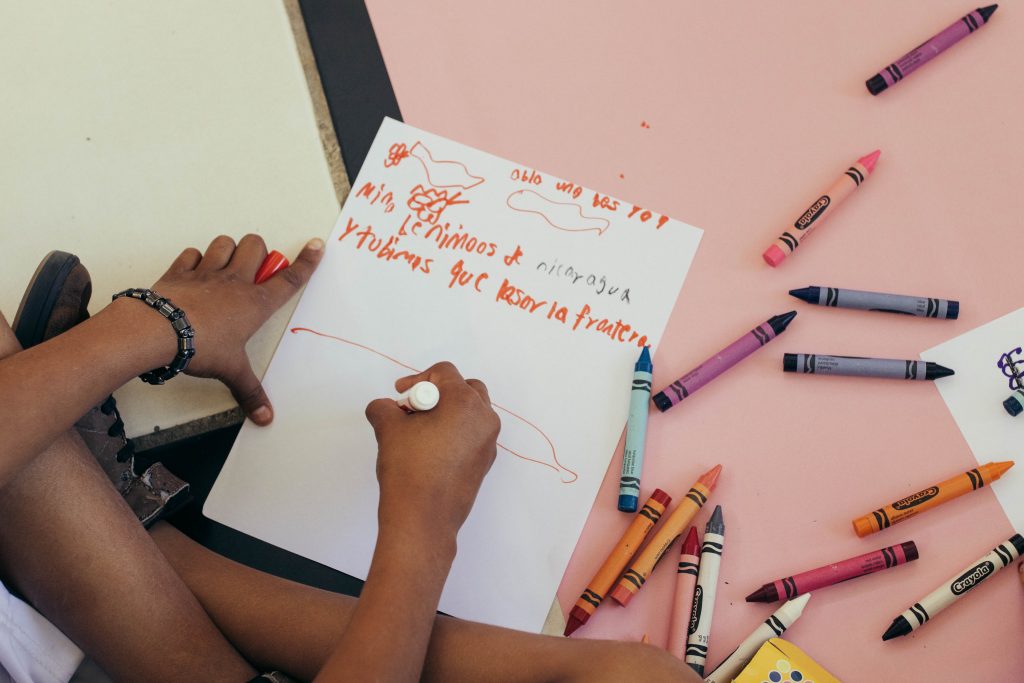

The trip across the border was fun for her, Deyling recounts in short sentences, with her black eyes fixed on a piece of paper on which she’s painting her memories.

-We went by car. Well, by taxi.

-And what’s your drawing of?

-The drawing about Costa Rica and Nicaragua.

Upon arriving in this country, she had to go back to school, but she believes that the lack of “papers” prevented her from doing so.

-And what did dad tell you?

-That he was going to try to do something to get me into school… After that, yes [I went to school]. I felt very happy.

Deilyn tells us her story one morning in early December, when it’s cooler with the winds around Christmas time. We sit on the floor of a large meeting area, together with about twenty girls and boys, and it’s impossible to listen to them one at a time. Everybody talks at the same time.

Some voices are quieter, but others, like a rooster crowing, ask for a different color marker to continue their drawing. It’s the covered patio of Casa Ilori, a program in which professionals provide emotional and educational care to girls and boys from La Carpio.

Deyling, with yellow blouse, seated with other children from La Carpio while we did an introductory activity with yarn to get to know each other. Photo: David Bolaños

Casa Ilori’s location is no coincidence. La Carpio is the largest immigrant settlement in Central America. Of the 25,000 people who live there, half are Nicaraguans or of Nicaraguan origin. For decades, residents there have suffered from urban segregation, insecurity and stigmatization.

Years ago, the people of Casa Ilori just played with minors in the street, but then they saw that they could do more for this community and began to build a space for classrooms, games, understanding and a kitchen where pots and pans are always banging. Later, the possibility arose for Casa Ilori to be one of the sites for Safe Spaces, a project of the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) so that migrant children and adolescents can share and spend time together. There are 16 Safe Spaces throughout the country, mainly located in border and urban areas with a high concentration of immigrant populations.

The team of journalists from The Voice of Guanacaste, Confidencial from Nicaragua and Interferencia de Radios UCR contacted the coordinators of Safe Spaces to be able to listen to Deyling and other migrant girls and boys— mainly Nicaraguans— who live in Costa Rica.

We set out to find out, in their own voices, if Costa Rica really guarantees their rights as it has promised in international laws and conventions.

Before meeting them, we received training in the use of language and timely approaches for children, given by psychologist Natalia Alvarado. Later, we went to Safe Spaces in La Carpio and in Santa Cecilia, in La Cruz in Guanacaste.

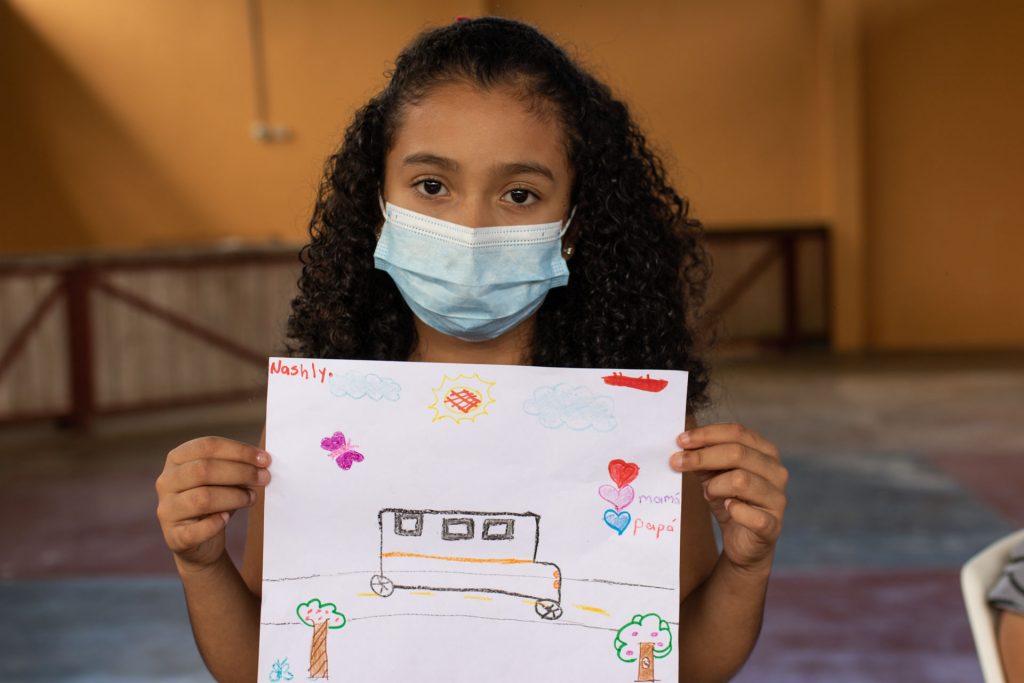

We also came up with a story to tell the children that we visited. The main character is a butterfly that meets friends in the places to which it migrates. In the activities that we did in both communities, after listening to the story, we asked them to do a drawing to tell us their own story, their daily experiences, their worries and joys.

This report delves into the lives of these immigrant children.

We traveled to Santa Cecilia in La Cruz in Guanacaste, a community just 12 kilometros (7.5 miles) from the border with Nicaragua. We spent time there with boys and girls in the community hall, where UNICEF started developing its Safe Spaces program last year. Photo: Cesar Arroyo Castro

Walls

Deyling is a strong girl. She wears a sunshine yellow shirt and smiles with her eyes. It’s possible that, up until now, Deyling didn’t have a very clear idea what those important papers that her father said he’d have to get to send her to school were. Technically, they were immigration legalization documents.

This documentation issued by the General Department of Immigration (DGME for the Spanish acronym) categorizes the stay of foreigners in the country, for example as a tourist, resident, refugee or processing naturalization. If someone doesn’t have their status defined, they’re considered a person with irregular, or illegal, immigration status.

In reality, Deyling was able to go to school even without “the papers” because Costa Rica is governed by a series of regulations that promise essential rights, such as education and health, to children and adolescents up to 18, no matter if they are Costa Ricans or foreigners.

The main document that backs this up is the Childhood and Adolescence Code, a national regulation based on the Convention on the Rights of the Child treaty, promoted by the United Nations to establish the basic human rights of this population. It has been ratified by 196 countries in the world.

However, along the way, immigrant families run into obstacles such as lack of money, discrimination or limited access to information that impedes their children from having an identification number and fully experiencing all of their rights. Not having “the papers” sometimes means being almost invisible to what some call “the system.”

It’s hard to know with certainty the number of undocumented immigrants in Costa Rica, precisely because many of these people don’t exist in official records. Reports from the Department of Immigration from 2017 estimated between 100,000 and 200,000 Nicaraguans with an irregular immigration status. At that time, the sociopolitical crisis of 2018 hadn’t yet erupted in Nicaragua, which significantly increased the exodus of citizens from that country. Some 100,000 Nicaraguans arrived in Costa Rica after April of 2018, according to a report from Inter-American Dialogue for Confidencial.

If we focus only on minors, the Ministry of Public Education (MEP) registers around 52,000 foreigners studying in the country’s schools. According to their data, the vast majority are Nicaraguans. Until last year, at least 21,000 (40%) of that group had an irregular immigration status.

Not all the boys and girls we met in Safe Spaces are among that number estimated by MEP. Some aren’t going to classes because there isn’t enough money at home, even though education is, in principle, free and mandatory in Costa Rica.

-I had to cross a wall. It was tall and gray– says Karla, a tall, thin girl with a very sweet voice who does go to school and also attends Casa Ilori.

Karla shows us her drawing of how she arrived in Costa Rica, when she, along with her mother and her brother, left Matagalpa, the Nicaraguan city where they lived. On the white sheet of paper, she drew a huge wall, the grass, a resplendent sky, a few clouds and then nothing. It’s all she remembers, she tells us.

Beyond her memories, that unpainted cement wall that marks the end of one country and the beginning of another is located just a few meters from the official Peñas Blancas border post, where dozens of travelers wait in lines that seem eternal during holiday seasons.

All kinds of Nicaraguan travelers have entered by crossing the wall for years. Some of them couldn’t afford to pay $40 per person for the visa that Costa Rica requires of them. Others weren’t coming on a trip: they were fleeing from violence or unemployment, looking for new opportunities, sometimes without even packing a suitcase.

Other people also enter meeting all the requirements, but then they stay longer than allowed and their legal stay expires.

Historically, the wall has been one of the best-known points through which immigrants enter illegally every year. But the border is porous, the authorities repeat all the time, and there are other more hidden trails.

-It took us a long time to come. And that’s all I have to say! – Andres, one of the children who attended Casa Ilori that morning, tells us abruptly and begrudgingly. Half distracted at times, Andres later expands on that:

-We came from Nicaragua. It took us many hours to come. Traveling from there and yes, we went over bridges and things like that, and we saw a lot of mountains, and things like that.

The great challenge once on Costa Rican soil is to legalize their immigration status and climb another wall that isn’t physical: truly incorporating these families into the society of the country that shelters them.

Costa Rica attempts to correct this with protocols and policies that, in the case of children, adhere to the Code and the Convention. The Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS), for example, guarantees people under 18 years of age and pregnant women care services regardless of their nationality, immigration status, economic status, etc.

“We have to give them [health services]. It’s mandatory”, reaffirms the CCSS’s head of the State’s coverage area, Eduardo Flores, specifying that the State pays for their care.

The same principle applies in public education. “We always work to ensure that the inalienable right to education is fulfilled,” says the head of Intercultural Education for the Ministry of Public Education (MEP), Victor Pineda. “We accept all people because it’s our responsibility.”

MEP has even higher aspirations. Schools should be a place where national and foreign students exchange their customs and characteristics of their identity.

“The idea is to be able to take advantage of all the cultural baggage that the foreigner brings to enrich the national curriculum, and to take advantage of the cultural baggage of all the other people who were already here to enrich the experience of the foreigner and for them to have a better socio-cultural adaptation in the country,” says Pineda.

As an example, the official cites schools in San Carlos, in the north of Alajuela, where they implemented teaching baseball into physical education programs due to the large number of Nicaraguan students and because that’s the favorite sport in their country.

It sounds good in theory, but in practice, these efforts have their flaws, according to Ercy Mendez, the director of Casa Ilori.

“I ask myself: how do they get included? How are children of other nationalities introduced in our classroom? Present it as wealth, talk about the subject of diversity. How will that be done in a classroom? I think it’s absent,” she said, based on her experience.

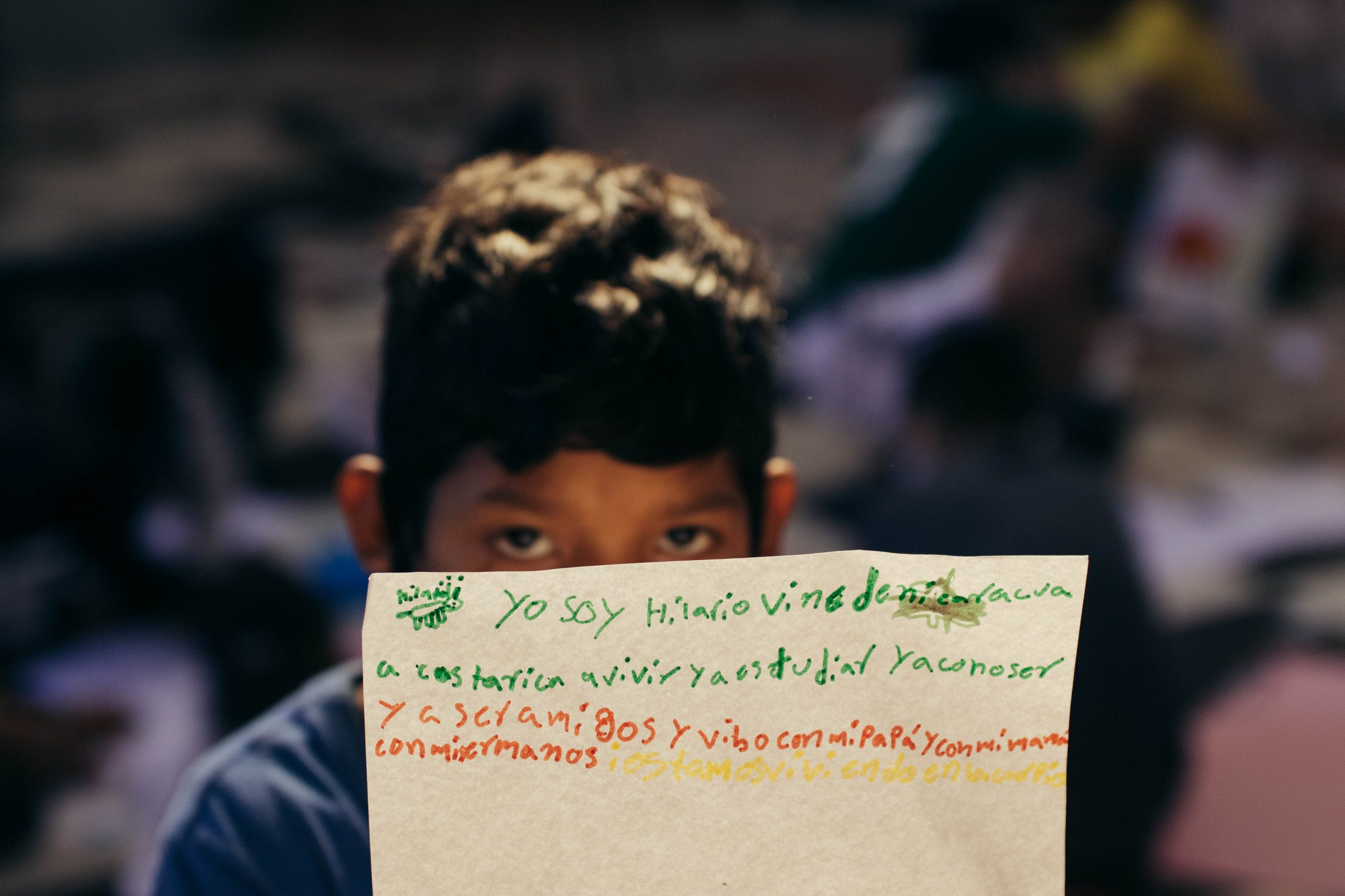

Hilario decided to use his piece of paper to write— instead of drawing— the path he took with his parents and siblings. They decided to immigrate from Nicaragua and he’s now making new friends. Photo: David Bolaños

Classroom experiences can be very different. There are boys and girls who spend time with many peers who are also immigrants, like them. Others are “few and far between”: they spend time with mostly Costa Rican students. Even if everyone can go to school, not everyone does so under the same conditions: if a child doesn’t have “papers”, he or she won’t get a diploma.

Due to these gaps, UNICEF has detected that those who have an irregular immigration status can’t completely exercise those rights.

“Here in Costa Rica, they have access to health, education, but since they have an irregular situation, their social inclusion, their full citizenship, becomes difficult. Often because they don’t have documents, they don’t have the course completion diplomas and it’s more difficult for them to enter the labor market. There are a series of challenges and barriers,” comments UNICEF’s representative in Costa Rica, Patricia Portela de Souza.

They are walls. They aren’t concrete like the one Karla crossed when she entered Costa Rica, but some are just as difficult to scale.

The coordinator of the Huetar Norte Regional Office of the National Children’s Trust (PANI for the Spanish acronym), Maria Amalia Chaves, pointed out that the institution can even file a court complaint against parents who refuse to send their children to school and force schools to receive the minors.

But the obstacle, many times, isn’t starting school but being able to graduate with all of the legal rights. In the end, the wall gets bigger, with more bricks: without an ID, they don’t get a diploma and then they won’t be able to go to university or have a job, explains the former deputy director general of immigration, Daguer Hernandez, who served in that position until the recent change in government administration.

Access

The team of journalists from the three media outlets went to Santa Cecilia in La Cruz, in Guanacaste, a community located just 12 kilometers from the border with Nicaragua a couple of weeks after having been to La Carpio. Although the December winds are already strong, they’re even stronger in La Cruz.

Last year, UNICEF and area leaders opened a Safe Space in the community hall, located in the center of town there.

For the program, doing so was necessary because it’s a cross-border community: Nicaraguan families and descendants of immigrants live there who face the challenges of accessing their rights in this area so far from the central offices of any public institution.

In total, 15 minors attended the appointment when we invited them to talk about their rights. Coni was one of them. She has cinnamon-colored skin and huge eyes. She tells us that she already knows how to read and write and that she wants to become a doctor.

At 12 years old, she could already know how to multiply, divide and use formulas to calculate the areas of triangles and rectangles. She could be starting high school, but she’s only been able to finish fourth grade.

-I don’t have the things. They’re going to enroll me next year. I haven’t been studying since “oooh”…

She came to Santa Cecilia when she was eight years old. She lives there with her father, an aunt, and three cousins (one girl and two boys). Her mom and the rest of her family live in Leon, Nicaragua, she says.

-My dad works selling at a market, in La Cruz, with my grandmother and another aunt. My dad hasn’t had money and my aunt gives him only 2,000 colones (about $3), so he hasn’t had time to buy me things. That’s why I’m not studying.

-Do you have a passport and everything?

-No, I only have the birth certificate from there.

Coni came to Costa Rica when she was eight years old. It’s been hard for her family to have enough money to send her to school but she hasn’t lost hope of going back to classes because she wants to be a doctor when she’s older. Photo: Cesar Arroyo Castro

Coni’s story is similar to that of dozens of girls and boys who enter Costa Rica illegally. When they cross the border, a physical journey ends but it’s just the beginning of a cumbersome path of requirements to exist in this country officially.

Coni’s dad, who doesn’t even have enough for school supplies, probably doesn’t have the $123 that Immigration charges for issuing the Immigration Identity Document for Foreigners (DIMEX for the Spanish acronym) either. That’s one of the big obstacles for many of these families, explains the former immigration deputy director general.

“A very large family, with seven children, who have to pay $123 for each child… Sometimes they think it’s better not to legalize any of them so that no one feels superior to the other,” Hernandez said as an example.

The rest of the bureaucratic procedures present other difficulties for families who sometimes leave their country with just a handful of clothes. Some authorities know about this in detail and try to do something about it.

For example, Immigration used to ask for the certified apostille birth certificate. They now accept other documents to validate the identity of minors.

“We authorize expired documents as long as they are legible, including the passport. We began to simplify until we reached a point where there were people who didn’t have the document but did have a way to prove ties with baptismal certificates and other documents such as certifications from PANI or the Courts of Justice,” adds Hernandez.

The Immigration Department began a project in December of 2020 to legalize children and adolescents. In coordination with institutions such as MEP and PANI, they identified students who had the possibility of having their DIMEX because they were children of Costa Rican parents, children of refugee seekers or because they were studying.

UNICEF collaborated with a financial fund that allowed families to reduce the DIMEX fee to $60.

In the pilot plan, which was conducted between February and April of 2021, 800 minors succeeded in becoming legalized. “It turned out quite well,” says Hernandez optimistically, although he knows that the number of girls and boys who need “the papers” is much higher.

With this special procedure, the term to obtain the identity document was reduced from two years to a couple of months.

“We started a second stage, no longer as a pilot project, but rather with a goal of 2,000 legalized people. We closed that project in November of last year. Right now we’re resolving and documenting, but 8,000 requests were submitted,” the former deputy director of Immigration specified.

Now Hernandez believes that they need to appeal to solidarity. “We’re working with different civic players so that they can collaborate to sponsor a child with their payment of $60,” he explained before leaving his post.

Many times, that solidarity fills the gaps left by the State. For a minor, having an ID in this country seems to depend on support from people. However, it’s their right and it’s the State that must guarantee it.

Nicaraguan boys and girls who live in communities with high concentrations of immigrant families, like La Carpio and La Cruz, often feel supported. They know that they share a history, origin and culture and that this is also a reason to feel proud. In the photo, four girls paint together in Casa Ilori, in La Carpio. Photo: David Bolaños

Inclusion

-We’re from Nicaragua. We came here. We walked across the border. The police had caught us. They were going to send us [back], but since we paid, they told us to cross.

Luis has all the bearings of being the older brother. He speaks first and next to him, Luisa, his sister, pays attention while he narrates the journey and obstacles that they overcame along with their mom, dad and other sister, to travel from Leon, Nicaragua to San Jose, in Costa Rica, a few years ago.

We also met these siblings at Casa Ilori, just a few blocks from where they live.

At times, she tries to finish the story that her brother began to tell with single sentences, but she’s more shy. She says that she likes this country but that she’s still getting used to it.

-She says that her friends treat her badly– Luis interrupts as if trying to translate his sister’s sentences when shyness and a few tears cut her story short.

It’s clear that Luisa wants to share something with us that she didn’t dare to capture in her drawing. It makes her sad and she can’t manage to express it. A while later, she finally feels comfortable and reveals something to us almost in a whisper:

-When I started, I was new. Then the next day, they treated me badly. They say that we’re poor. They say that we’re good for nothing.

The words that Luisa couldn’t express portray the tough experience of many other Nicaraguan people. For them, being mistreated goes as far back as their immigration and is one of the most gigantic walls they have to face along their journey.

This has been documented by university studies, sociologists and other experts in newspaper articles. This ends up causing their mental health to deteriorate. They manifest symptoms of depression, such as tiredness, sadness, confusion and humiliation, according to a study with Nicaraguan immigrants from the Psychological Research Institute of the University of Costa Rica (UCR).

The boys and girls are no strangers to all of these emotional changes, explains Natalia Alvarado, psychologist and professor at UCR.

“They leave friends, they leave family, which is important to them, their school, classmates, their physical space, the place where they grew up, to reach a place that, in theory, offers them better living conditions but it’s not always like that,” she relates.

Add to this that on many occasions, immigrant parents, due to the same discrimination, must opt for informal jobs with low income and long hours.

-Mommy has four [jobs]… Well, now she has five, because she came to drop me off because she had to go plant beans, that’s one. She sells shoes, she sells clothes, she sells colognes, and she takes orders.

Nairin tells us that. She’s 10 years old and she is the most restless of the group in La Cruz. While we do the activities, she suddenly stands up to do the splits or to do cartwheels. She was born in Costa Rica, but her mother is a Nicaraguan who immigrated to Santa Cecilia.

-Mommy’s always tired. Dad is working there. He has to take care of a house.

The fundamental rights for girls and boys go beyond guaranteeing that a doctor sees them or that they can attend school. It also means that they grow up in an environment surrounded by love and understanding, that they aren’t made fun of for their way of speaking, dressing or their customs. It also implies that they can play, have fun and have an ID document.

But it’s not easy to combat the prejudices of other families, officials and children who have grown up listening to xenophobic talk.

This happens, for example, when they receive medical care at CCSS. “For Costa Ricans, it’s hard to know what it means to be an immigrant,” says Flores, the head of the institution’s coverage area, adding that there are always Costa Ricans who don’t understand that immigrant children have the right to receive free care.

These limitations reinforce fears that children already carry from their immigration experiences, noted the director of Casa Ilori, who has seen them inhibited and afraid to express themselves and live freely.

“And that moves me a lot to do the best I can so that they don’t feel [something is] lacking, so that they feel complete, so that they feel they have the right,” says Mendez.

Pie de foto: Hilario is one of the children who lives in La Carpio and goes to Casa Ilori. Ercy Mendez and other groups, activists, organizations and entities like UNICEF work to ensure that his rights, and the rights of dozens of boys and girls from immigrant families, are fulfilled. Photo: David Bolaños

The moms and dads of these children also feel afraid when the hope of a better life remains just that, an illusion.

Geographical and social exclusion has opened cracks for the emergence of violent behavior among some communities. Robberies, assaults, domestic violence, police violence and drugs are among the concerns of neighbors. This was reflected in a study by four researchers on La Carpio.

It’s not the norm. The settlement is stereotyped in the media as violent and unsafe, but visiting this binational community allows us to realize that, in reality, its inhabitants are hard-working people who seek to put food on their tables every day through different enterprises.

-Is there anything you don’t like about here?– We asked Jostin, a smiling and talkative boy from Casa Ilori, who has personally experienced the challenges of living in a community with symbolic walls, cracks and landslides to undermine his full integration into society.

“Only when they shoot bullets in the street,” he replies after thinking about it for a little bit.

-Does that happen often?

-Yes. Man, when one sells more, the other doesn’t, they fight.

– And that scares you?

-Yes. I throw myself to the ground.

Being

-So, when we say: ‘boys and girls have rights, what do they have rights to?’ we ask them at the end of one of the sessions.

The children’s voices at the top of their lungs flood the hall of Casa Ilori:

-To eat! To go to school! To study! To play! To learn!

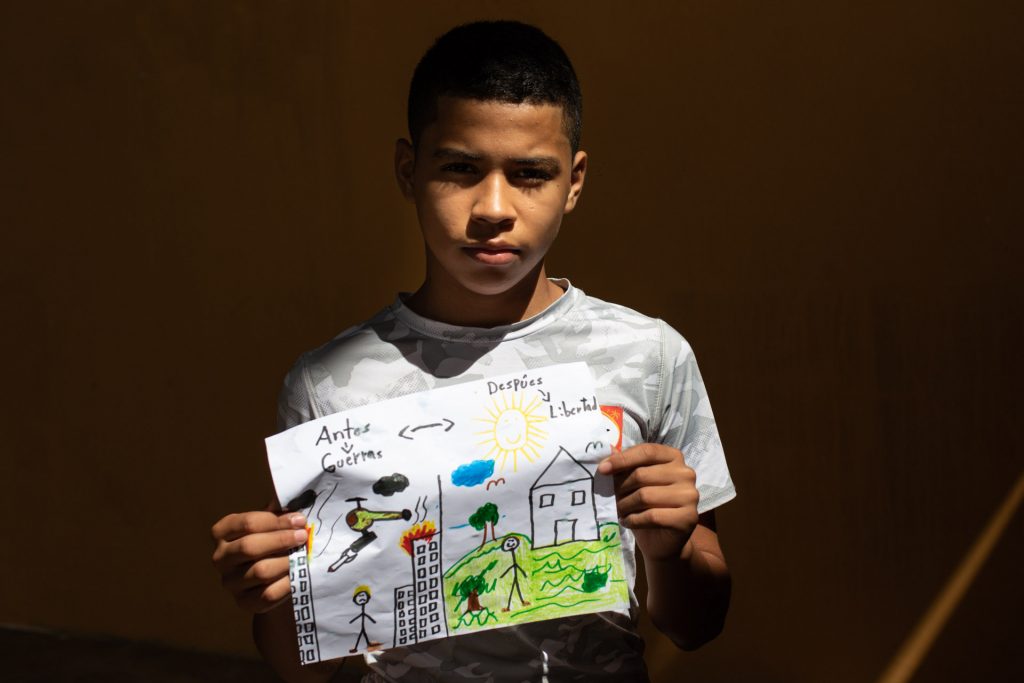

“It’s interesting to see how in their drawings, Costa Rica also represents a place of hope, a place where they can find better living conditions. This is quite revealing and beautiful because the children do believe in the possibility of living better or, at least, living differently from how they lived in their country of origin,” explains the psychologist, Alvarado, after contemplating the pictures that the girls and boys made during the activities, which this team collected to show to her.

The mistake that adults often make is believing that because they’re in their childhood, they don’t realize what’s happening, adds the psychologist. “We have to give them that space to voice, vote, listen, explain and see how they feel about this.”

Guaranteeing their rights is allowing them to be: to live their childhood in safety, with education, health, recreation and allow them to maintain pride in their roots, without ever feeling ashamed of it. Jostin knows it and brags about it.

-How are you doing now here at school?

-Good.

-Do your classmates bother you?

-No. There are more immigrants here than Costa Ricans.

-That’s true. So do you feel proud to be Nicaraguan?

-You feel the pride of being Nicaraguan, like Presto coffee- he sums up with half-closed eyes and an expression that betray his smile hidden behind his face mask.

Other contributors to this special report: Katherine Estrada, Elmer Rivas, Alejandro Duran, David Bolaños, Cesar Arroyo, Ruben Roman, Roberto Cruz and Jennifer Vega.

Comments