As you are reading this article, it is likely that someone else is cutting down a tree native to Guanacaste that is at risk or danger of extinction – permits or not.

Studies from the Costa Rican Technological Institute (in Spanish, TEC) have warned of the consequences of this practice since 2000. If species like Spanish cedar, glassywood, cocobolo, and white guanacaste begin to decline, it will not just affect the survival of other plants and animals, but those same species will become less commercially attractive.

How? A scarcity of trees of the same species ends up weakening their genetic quality, which means that the trees will be less robust, fertile, and lush. Depending on the species, they will grow more slowly. This reduces their commercial value.

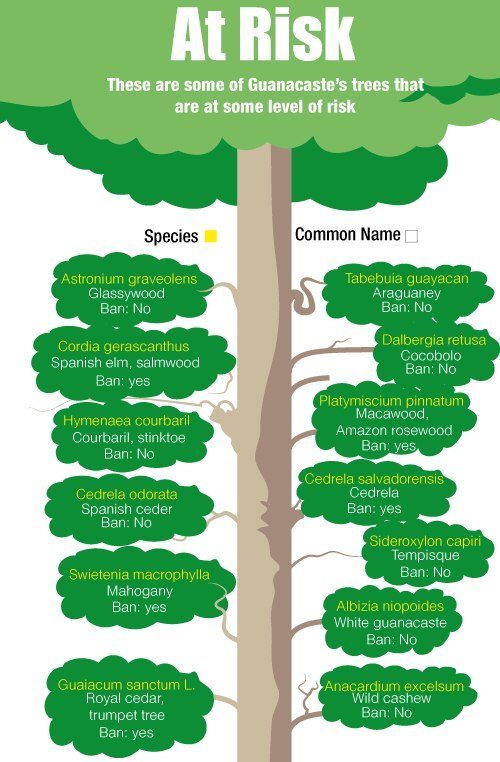

Ruperto Quesada, researcher and forest engineer at the TEC, has followed Guanacaste’s species that are in danger of being lost. Of the thirteen that are at risk, according to his studies, only five enjoy government protection with a ban against their commercial exploitation.

“One species could disappear and nobody would realize it. But you have to consider the habitat in general. When you lose a tree, you lose all of the symbiotic relationships that the species had. If a species is missing, then habitat’s entire food chain will fail.”

The problem is greater than illegal logging: many forest species have been placed at risk by extremely common human practices in the province such as ranching, farming, controlled fires, and forest fires. These activities greatly reduce the chance that the tree populations will regenerate.

When scrubland is burned, for example, the chance that a secondary forest will grow there is lost. Some at-risk species, like cocobolo and tempisque, need a habitat like scrubland in order to reproduce.

Experts explain that when people stop ranching or farming, the land is first taken over by brush and then by woody vegetation or secondary forest. This acts as a protection mechanism so that the largest forest species can grow.

“The secondary forest begins a series of processes that prepares the land so that other species can thrive,” explained Quesada.

Danger Without A Ban

Between 2000 and 2002, Quesada studied scarcity of species whose exploitation was not banned by the State but whose diminished presence in the countryside indicated strong vulnerability. He focused on the white guanacaste, wild cashew, glassywood, Spanish cedar, kapok, cocobolo, courbaril, and tempisque.

The forest engineer found that in Nicoya, Nandayure, and Hojancha there was a notable lack of thick glassywood trees and that every tree on his list had fewer than one tree for every three hectares, which is the level established by the Costa Rican government to stop the exploitation of a species, as is outlined in the Principles, Criteria, and Indicators for Forestry Management in Costa Rica.

So why haven’t they been banned? According to Nelson Marín, director for the Tempisque Area of Conservation (in Spanish, ACT), studies for banning the exploitation of a species must be performed by the National System of Areas of Conservation (in Spanish, SINAC) at the national level. Quesada’s study is not enough.

A Matter of Size

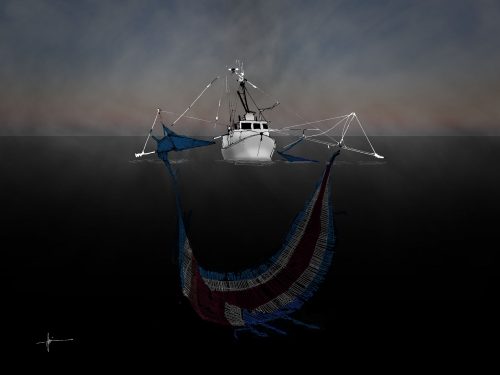

The scarcity of glassywood trees has happened because commercial logging directly affects large-diameter trees. One cubic meter of cocobolo can cost over $4,000 in Asian markets; the more wood per cut tree, the better.

Large trees are essential to each species’ reproduction as they have a greater capacity to reproduce. “If the biggest trees are taken away, they take their trees and the chain of growth is broken,” explained Quesada via telephone.

However, logging permits are often rejected mainly for young, thin trees, according to the director of the ACT, who also added that logging is regulated by forestry permits.

Regardless of how much forest cover the province recovers – and it already has – Guanacaste’s most vulnerable trees will have little chance to survive or increase their numbers if the State continues to allow their exploitation, according to Quesada.

Marín agrees. He stresses that the Government must impose restrictions on the species studied by Quesada due to their small presence, slow growth, and reproductive difficulties.

Another example of poor forestry management is the illegal logging of cocobolo. With rising prices abroad and increasing numbers of illegal harvests, the pressure is mounting.

“One cocobolo needs more than 300 years to reach a 50-centimeter trunk diameter. Its growth rate is very low. There is an enormous pressure for the wood’s exploitation which will, if it’s not stopped, lead to its extinction. The glassywood and dare I say even the courbaril, sapodilla and all hardwood species are moving along the same path,” said Quesada.

Not everything is bleak. The cocobolo’s future could improve in the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) declares it an at-risk species in Costa Rica.

CITES is evaluating prohibiting this wood’s trade internationally, according to the secretary of the Costa Rican office, Grace Wong, who said that the results will be ready in two months.

Meanwhile, time is running out for threatened species if these decisions don’t arrive. “Conditions of drought and scarcity in the area are the consequence of unwise use of resources, including trees,” said the head of the ACT, Nelson Marín.

Oasis or Isolation

You might ask this article, “What is the problem is there are fewer trees of one specific type on a farm? There are plenty of other species that aren’t scarce. And what are the conservation areas, then?”

It’s true: trees in protected areas have a clear advantage in survival. However, these oases could become closed areas where the populations become isolated and fragmented.

“Protected areas do not guarantee the genetic quality of species in general. The truth is, these are nuclei for reproducing outside of the areas. That’s why, on the outside, we need to optimally and efficiently use them in order to preserve the species, explained Marín.

Comments