Bertilia sleeps sitting up on an old couch in her living room, with her feet up on a plastic bench and her arms wrapped around her hips as if she’s hugging herself. She sleeps uncomfortably like this, with stabbing pains that get worse every day, because in bed, she gets uncontrollable dizziness that can cause seizures. This is how she has lived, or tries to live, since 2018, when her former partner fractured her skull in an attempt to kill her.

She’s only around five feet tall and has a robust build, which she insists she has developed with age. She has a streak of white hair in her short black hair that falls to the right side of her forehead. She says it’s fashionable, but it also hides the scars that she has had on her head since that December 31, when she went to the emergency room with some pieces of a wooden club embedded there.

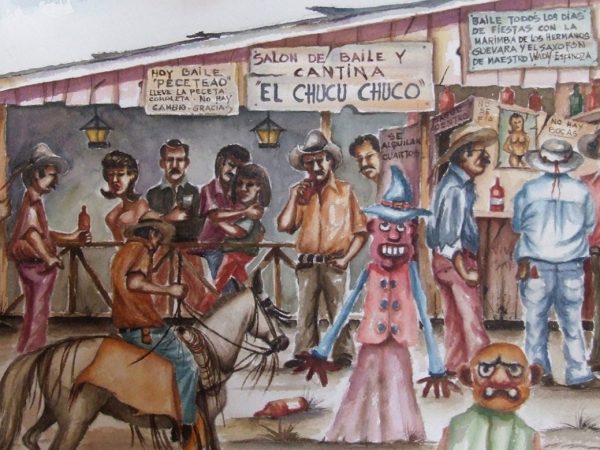

During the year-end festivities, Santa Cruz was full of the sounds of fireworks, bullfights and laughter, along with the sirens of the ambulance that took Berti to the hospital while she hovered between life and death. It happened there, in the canton that is the cradle of folklore in the province, but which is also the canton with the highest number of gender violence crimes reported since 2015, according to an analysis performed by The Voice of Guanacaste.

In 2019, for example, the Santa Cruz Family and Domestic Violence Court reported that at least 1,279 women filed complaints about suffering from domestic violence, the highest number in all of Guanacaste since 2016.

Bertilia was one of them, although she says the word “victim” just doesn’t suit her. When asked what her story is, she usually responds: “a survivor one.”

The aggression on December 31, 2018 was neither the only nor the first that she experienced. Rather, she has lived through a string of violent stories that began when she came to live in Santa Cruz as a child.

Back then, she was told that the world was divided into two: that of men, who are born, grow up and begin to command and take ownership of everything; and that of women, who are born, grow up and begin to be commanded and owned by men. “That was my reality,” she said in a quiet voice, as if she were ashamed.

This story is continuously repeated in Santa Cruz households, according to Rosario Gutierrez, the community leader against gender violence.

In Santa Cruz, we are all born with a dose of patriarchy, which we women in Santa Cruz suffer from. They shut us in. They make us their objects. Violent history defines us,” she affirmed.

Berti got married when she was 22 to a man 13 years older than her. During the first year of marriage, her husband beat her at least once a week. If she didn’t cut the tomatoes well, if she didn’t clean the house the way he liked it, if she smiled a lot, if she didn’t smile a lot, if she walked looking straight ahead and not down, if she said hello to the neighbors… any excuse would do to abuse her.

Although Berti had her own restaurant, her husband kept all of the accounts. When he knocked her teeth out, she couldn’t go to the dentist on her own. “There came a point where I didn’t speak at all to save teeth,” she related.

In the nearly fifteen years they were together, he fractured part of her skull and broke her hip in two. The latter put her in the hospital for three months, with the possibility of not walking again.

Today, Berti still limps slightly, a result of the fracture to her hip. Now she raises chickens and rabbits to survive since she’s had so many injuries that she can’t spend much time cooking. She’s still happy, she said, because when she sells the animals, the money goes into her bank account and not someone else’s. She spends it on herself, because she earned it, an idea that was revolutionary for her and was impossible to think about ten years ago.

She didn’t know that she was living in a circle of violence. Her husband wouldn’t let her talk to her family, and when she talked to her women neighbors, they told her to avoid talking so much or looking at other men. That was their magic remedy, since they were also beaten by their partners.

At night, one would hear a concert of sobbing and screaming, because other women were being beaten in the neighborhood. That was normal,” she said.

Violence and Machismo

For Rosario Gutiérrez, the machismo culture that prevails in Santa Cruz makes it more difficult for victims to realize that they are living in violence. As a facilitator of empowerment workshops focused on gender in the community, she constantly spends time with women who don’t know that hitting and insults are not normal behaviors.

I have received threats from men telling me that I messed up his wife, because since she now knows about empowerment, now she no longer allows herself to be yelled at or hit,” Gutierrez affirmed.

The province of Guanacaste reports the third highest number of 911 calls in the nation for help due to domestic violence, following Limon and San Jose.

So far in 2020, 97 out of every 10,000 Guanacastecans made a call denouncing a case of domestic violence. Santa Cruz is the canton in the province with the second highest rate of complaints, following Liberia.

According to Gutiérrez, Santa Cruz is the cradle of Guanacaste’s culture and tradition, preserved for centuries, both the good and the bad. “We have super national, super patriotic songs, but they generally say horrible things against women. If they don’t respect us in their lyrics, how will they respect us at home?” she theorized.

A study by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations suggests that there is a large gender gap in areas that are far from the capitals of Latin American countries. In these places, like Santa Cruz, access to gender studies is more limited and the communities are more traditionalist and conservative.

Bertilia believes the same. She describes the province as a different world, separated by the Tempisque River and the macho traditions. To her, it is a world where men have special permission to dominate their wife and children.

There (in the Greater Metropolitan Area) you don’t see the things you see here. For example, here a man comes and hits a woman in the street, and that’s just another Friday. It’s hard to see that there. One has to be submissive to what they say, because they are always right here,” she lamented.

After the broken hip, Bertilia managed to separate from her husband and leave her home, taking all of her belongings with her in a few garbage bags. She went from having her own restaurant to being unemployed and living in a flophouse with two of her three children. Of course, she said that didn’t last long, since she started working double shifts to get out of the “slums” and move up in the world.

Crédito: Dunkan Harley

“I had to keep going for my children and myself,” she said. She did it. She moved back in with her mother, a relationship that she had lost for years. In addition, she started taking empowerment courses at the National Institute for Women (INAMU), where she managed to say that she was a survivor for the first time.

Three years later, she got together with another partner, as part of the rehabilitation of women who have experienced domestic violence. However, it was another man from Santa Cruz who physically and psychologically abused her from day one, she said.

He would throw food in her face when he didn’t like how it turned out, check her cell phone when he had a fit of jealousy and hit her every time he was angry. She sums that short story up like this:

“He would throw me to the ground to hit me, and I somehow convinced myself that I could endure it. I would tell myself, ‘well, I already lived through it. I can live through it again. There’s no problem,’ but when you already know that this is wrong, you can’t. And after a little more than a year, I told him no more, that we weren’t going to stay together anymore, and he told me ‘you are never going to leave me.’ I couldn’t be with him, so without caring, I told him to go pick up his things, no more now.”

He was the one who tried to kill her on the night of December 31, when Bertilia went to a friend’s house to hem some pants that she was going to wear for the first time that day.

According to the official account that she told to the authorities, he saw her riding in a vehicle towards her friend’s house, followed her, and when she arrived, while Bertilia was at the entrance, he hit her on the head from behind with a kind of club. Then he assaulted the friend too, leaving her unconscious. The paramedics were afraid that Berti wouldn’t make it to the hospital alive.

So Why Don’t They Report It?

Bertilia’s attackers are still free.

The first one, her husband, never had charges of domestic violence filed against him. Although the neighbors called the police on him at least once a month, they did nothing. In fact, one of them told Bertilia that “her worst mistake” would be to testify because if her husband went to jail, she would end up without food. At that time, the police officer recommended that she stop “bothering” her husband so much.

Since then, I kept silent about what was happening to me, about the ordeal that I was experiencing. Because of what he told me, supposedly not to harm myself or my children,” she lamented.

A lawsuit for attempted murder has been open against the other man for two years. However, the case is at a standstill.

Bertilia says that her attacker has a restraining order and arrest warrant against him, but this hasn’t prevented him from going to her home or to the places that she frequents. Her children, both of legal age, have reported several times that they saw him in the center of Santa Cruz, “as if nothing had happened.” The response they always get is that “they are doing the best they can.”

The Voice of Guanacaste requested information from the Judicial Investigation Agency (OIJ) about the status of the investigation and the measures they have taken to protect Bertilia. However, as of the close of this edition, we didn’t get a response.

Berti’s day to day life consists of taking safety measures to avoid running into her attacker and going to medical appointments to try to improve the quality of life that she lost after the attack.

That episode left a mark on her life physically and emotionally. Two years later, she has splinters in her brain and in the back of her right eye. That is why Berti has to sleep sitting up.

Although she claims that she doesn’t hold a grudge against anyone, Bertilia wants justice for herself and for any other woman, because she’s afraid that another woman will end up suffering the same treatment at the hands of her ex.

Dream to Survive

After the attack, the doctors ordered all of the mirrors in all of the women’s rooms to be turned over so that Bertilia couldn’t see her reflection. They feared that if she looked at her disfigured face, she would have suicidal thoughts. Instead, when she saw her wounds, she smiled. “At least I didn’t end up that ugly,” she joked.

Berti is happy and dreams as an act of resilience. She said that the reason she didn’t die after those beatings is because she wants to fulfill several goals: travel and dance at each destination, get piercings and tattoos all over her body, and get back to cooking, but now because she enjoys it and not because someone else tells her to. She can set these goals now in her 50s, because for the first time she feels free.

She has lived through storms and a lot of pain, but now she divides her life into two stories: one, a tragic tale full of abuse and the other other, the one she uses to get through each day with that broad smile of hers, the story of a dreamer whose goals keep her alive.

Next year, when she can save enough money, she plans to get a tattoo where the wounds on her arms are. She says she wants to rewrite her story, delete the victim and become her own heroine, the one who built her own protective wall, got rid of violent traditions and now lives to be happy, to be Bertilia.

Comments