In January of 2022, the director of the Tourist Police for the Public Force, Fulvio Fernandez, met with the Kolectiva Nosara Mujeres Unidas (Nosara Women United Collective) to better understand the crisis of sexual assaults in the district. Fernandez arrived in Nosara in response to a series of reports of sexual assaults at community parties published by The Voice of Guanacaste, with support from the women’s collective.

On that occasion, the activists recalled, the captain listened to their concerns and demands. They said that Fernandez acknowledged that there was a crisis of sexual crimes but defended the protocols that the tourist police follow and the attention that his team provides on coasts such as Nosara.

According to the women interviewed, Fernandez promised them three things:

- More patrolling in “key areas”

- Working together with Nosara’s medical corps to attend to the victims

- Training the police staff on gender issues

The general director of the Public Force in Costa Rica, Daniel Calderon, confirmed that they held this meeting after the reports. He also said that he is aware that they made commitments at the meeting to have an impact on the sexual crime crisis. Calderon referred to the meeting as “a first approach” to the problem.

The collective, however, hasn’t seen any changes.

After that meeting, we were in contact, insisting, but he never came back. They never contacted us for training sessions. Months later, we again heard about another case of attempted rape,” said one of the activists, who asked not to reveal her identity.

La Voz tried to talk to Fernandez to find out why he hasn’t initiated the promised projects, but we didn’t get a response by the deadline for this report. Omar Granados, police chief in Nosara, was on vacation, and Nixon Salas, head of the delegation in Nicoya, declined the interview by order of his superiors.

This outlet did manage to talk with Calderon and with the regional director of the Public Force for Guanacaste, Pablo Bertozzi. Through them, we found out how the teams are working in Nosara, the progress on the investigations, and if security as improved in the district in these months.

Even before the reports, the Nosara police station has to abide by the 72-hour protocol for taking care of victims of sexual violence in the next three days after the event. This means that if a victim arrives at the Nosara police station or calls 911, the police force must safeguard evidence for the case until agents from the Judicial Investigation Organization (OIJ for the Spanish acronym) arrive and coordinate with medical personnel regarding the victim’s physical and emotional stability. We addressed this issue in this article.

The problem is that OIJ’s data reveals that very few victims report the aggression within the time indicated by the protocol. Many never report it. In fact, in the last 3 years, only five women reported their assault to the district police. Three of them did so in 2021.

OIJ indicated that the Public Ministry might have more reports related to these crimes in the canton from women who went directly to the Prosecutor’s Office to present their cases. We requested this data from the ministry but they didn’t provide it by the close of this edition.

Among the survivors we interviewed last year, we know that only one has open legal proceedings. She filed the complaint several weeks after the rape happened. She said that she needed to recover emotionally before doing it.

At that time, she said that for her, the process had been re-victimizing and “emotionally draining”, she had to travel to at least three police stations and stated that several officials made offensive comments blaming her for the assault.

Calderon stated that most people in coastal areas are unaware of the institution’s protocols. That’s why he assured that there are police departments already working on creating campaigns to familiarize residents and business owners in tourist areas with these types of procedures.

OIJ is investigating each case individually and each one is at different stages of progress. They declined to comment on further details because the investigation stage is private. However, Calderon confirmed that at least the Public Force is working to create a kind of analysis that helps them understand the profile of potential perpetrators, which population is most vulnerable and which places are frequented by both victims and attackers. That way they might be able to redirect their resources more strategically.

The director also acknowledged that most Public Force officials lack sensitivity in gender issues but he didn’t offer any prompt solution for Guanacaste.

The wounds that a situation like this leaves on an emotional and psychological level are deep. It’s very valuable that the first attention given by the police be comprehensive because it can determine the entire investigation,” admitted the director.

The Public Force is working together with the National Women’s Institute (INAMU for the Spanish acronym) to give workshops to its officials on issues of gender and sexual violence. They have already trained at least 60 police officers in Limon. The Chorotega Region is not yet included in the training sessions.

So what changed in Nosara?

The simple answer is: practically nothing. The regional director of the Public Force in Guanacaste, Pablo Bertozzi, justified the non-existent changes citing the lack of budget faced by his unit. The director explained that they don’t have money for new positions for Nosara (nor for the rest of Guanacaste) and they can’t increase patrols due to the lack of gasoline.

Bertozzi said that security can only improve when the executive branch grants more of a budget for these kinds of operations.

The official stated that although his teams are working “the best they can” to prevent crimes of sexual assault, the tourists aren’t being very “careful enough” to avoid them either.

We have to further reinforce the concepts of security, make people understand, Costa Rican tourists, our foreign tourists, that they cannot simply hang out in the streets and on the beaches and in hidden nooks and crannies thinking that nothing is going to happen, because that’s not so. Things can happen,” stated the director.

I asked him if he believed that the victims should assume the responsibility due to the deficiency of his police department and he retracted, indicating that he was not blaming them. He also doesn’t believe that his team does their job badly, but he believes that “everyone should do their part in the face of public safety.”

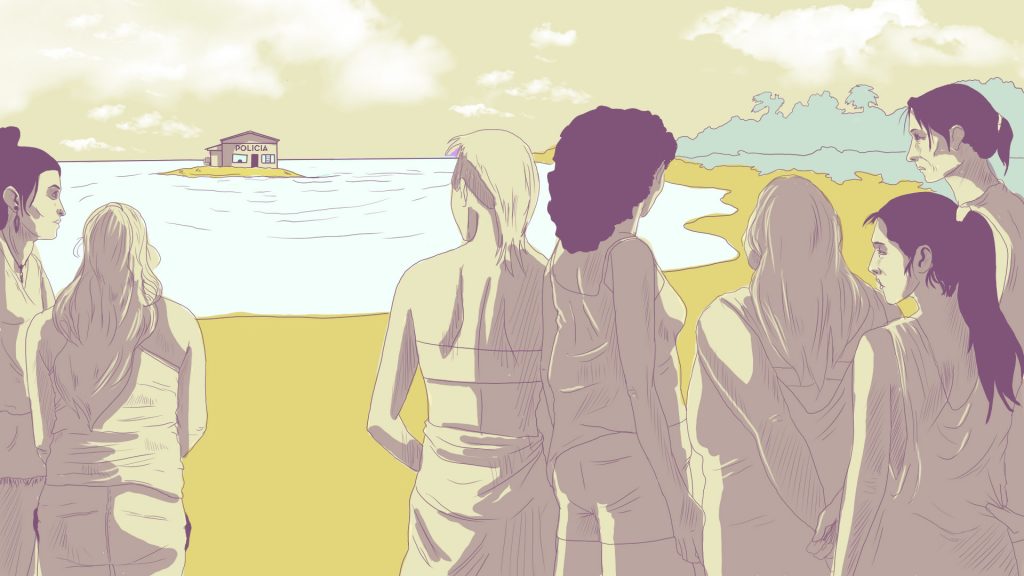

The women’s collective feels that there is a gap between police actions to prevent and address crimes of sexual violence and the community’s need for assistance. Picture: Dunkan Harley

To Larissa Arroyo, a lawyer with expertise in human and gender rights, the official’s statements are “unfortunate” and she believes that it’s a consequence of a lack of sensitivity within the police forces.

The issue here is not that tourists come believing that they are going to be safe in Costa Rica. The problem is that we aren’t a safe space for them and that the State isn’t doing anything to avoid it”, the expert affirmed.

Costa Rican Government fails to care for victims

Calderon believes that the Public Force is trained to deal with sexual crimes since they do know how to execute the 72-hour protocol from their training. According to him, the problem lies in this procedure not taking into consideration how to help the victims emotionally.

To carry it out, the Public Force or OIJ work together with institutions such as 911, Health, PANI and INAMU to preserve the physical and emotional health of the victim in the first 72 hours after the sexual assault or even later after that time.

These moments are key to comprehensively taking care of the victim’s mental and physical health, to prevent pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections and even the acquired immunodeficiency virus. With this program, they also collect all the evidence as soon as possible to start the corresponding investigations of the cases.

Generally, the Public Force is the first institution that attends to the victim, and the police officers are responsible for protecting the crime scene for the OIJ agents.

“We concentrate a lot on giving the legal part [to the victim], which is what has to do with the [72-hour] protocol. The new workshops specifically aim to prevent the agent from becoming a re-victimizing entity. And according to the accounts we’ve seen (in cases of sexual assault), that’s where we need to work on.”

In an interview conducted in November of last year, the head of the Technical Secretary for Gender and Access to Justice, Jeannette Arias Meza, stated that since the protocol initiated in 2011, they have had to make adjustments in how it’s applied because they saw that there were certain places where it wasn’t being practiced as it should be or it wasn’t being applied at all.

[The victim] had to give a statement to the administrative police, a statement to OIJ, a statement to the Prosecutor’s Office, a statement to the forensic doctor, and so on, practically nine interviews,” the expert said.

That’s why the protocol underwent an important restructuring in an attempt to reduce the number of times that the victim has to testify and interact with the authorities. However, some experts don’t think this is enough.

Larissa Arroyo, the lawyer with expertise in gender issues, believes that this type of process tires the victims and discourages them from reporting what happened or continuing with the judicial process. In fact, another one of the survivors who reported her case to The Voice of Guanacaste tried to file the complaint with the police, but the number of procedures and steps to follow caused her to stop following through with the accusation and she left the country.

“The whole process, as it is currently designed, is extremely complicated and poorly designed. They don’t give security to the victims. A woman can’t be sure if they’re going to treat her well, if they aren’t going to judge her,” the expert stated.

Education and attention to other crimes could contribute

The lawyer thinks that the conditions of sexual assaults are agravated in a town like Nosara, where the state budget is even smaller and reporting a sexual assault becomes a more challenging task.

8M protest in March of this year. One of the main issues for women was more action for cases of sexual violence.

“If the system already isn’t working in and of itself, well, then we can understand that in a small place like Nosara which is neglected by the state in terms of budget, it’s even more complicated. What should be reviewed isn’t the number of complaints that are filed, but rather the reason why they aren’t filed,” Arroyo affirmed.

Arroyo believes that although it is a good sign that the Public Force is interested in the integral training of its officers to care for victims, she believes that efforts should be inter-institutional. In this way, organizations such as the Ministry of Public Education (MEP) should help to educate on gender issues from an early age.

Awareness campaigns are just putting a little piece of paper on the wall and that’s it. To talk about results in the long run, we would have to talk about a gender education plan incorporated from MEP, breaking the barriers to these issues,” said the lawyer.

The Gender Equality Observatory of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) found that there are a series of factors that increase the risk of men committing acts of sexual violence. Some of these are educational backwardness, illicit drug use, gang membership and a history of violence during their childhood.

Arroyo also pointed out that the lack of action in cases of sexual violence is due to the lack of priority given to these issues within the institutions.

What is important is not the resources issue, but the political willingness. We have to see precisely what is more of a priority for the authorities than this, despite the fact that gender-based violence is aimed at at least half of the population,” she said.

The chief of police in Guanacaste, Pablo Bertozzi, agreed that there is an important correlation between high rates of drug use on the coast and cases of sexual assault. The official believes that, as they combat these drug networks, the cases of sexual assaults could also go down.

Comments