Marta Bello was frightened that Susan, her youngest daughter at age 14, would repeat the family history. Maria got pregnant for the first time at age 15, and her older daughters at ages 14 and 18. That’s why she supported Susan when she had a birth control implant inserted to protect her from pregnancy for three years.

She is studying and if she gets pregnant I will have to take care of the baby. It would be a setback for her. She wouldn’t be able to go out or go anywhere,” Bello says.

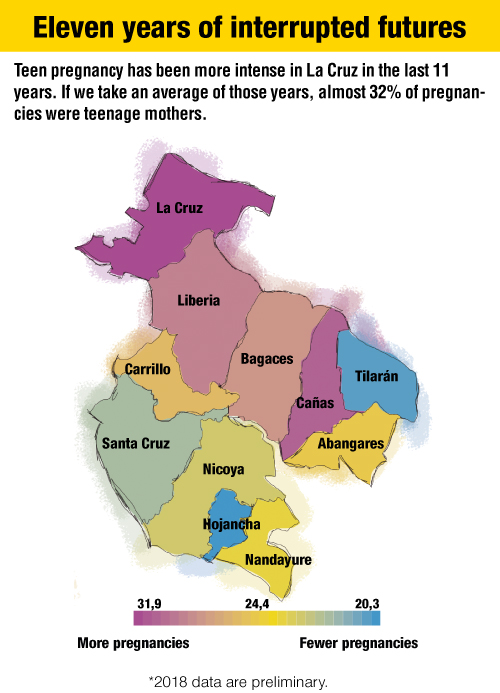

In the series of challenges on escaping poverty, unemployment, and violence in the canton that borders Nicaragua, teen pregnancy ranks high. An analysis by The Voice of Guanacaste based on birth data from the National Statistics and Census Institute (INEC) found that in the last 11 years, La Cruz has held first place in the province with the greatest number of teen pregnancies (see map).

Generations evolution: Paola (left) gave birth for the first time at 18 years old. Her sister, Susan (center), 14, had a birth control implant a few months ago. Their mother (right) was also a teen mom at 15 years old.

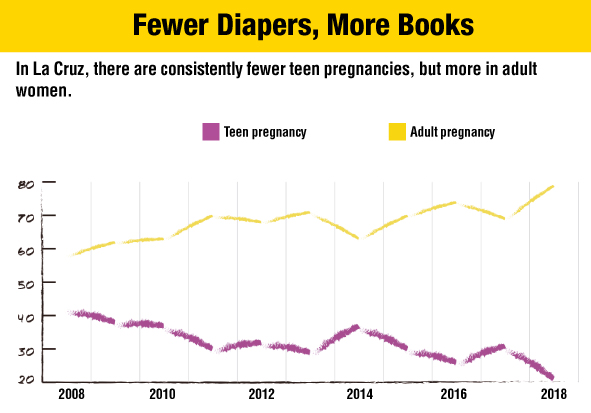

But local efforts have started to change the picture of what life can look like for Susan and young girls like her. From 2017 to 2018, La Cruz was the canton with the greatest reduction in teen pregnancies in Guanacaste (see chart).

In 2017, 39 of every 1,000 adolescents (from 10-19 years old) from the canton gave birth, the eighth highest of 81 cantons in the country. In 2018, La Cruz reduced that number to 24 per 1,000 (15 teen pregnancies fewer for every 1,000 than in 2017).

Several institutions and the United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA) began initiatives in 2016 in order to tackle the problem. While it is early to credit the initiatives to the decline, the data indicates a correlation.

According to data provided by the Costa Rican Social Security (CCSS) to The Voice of Guanacaste, in 2017 alone the local health ministry in the canton inserted 423 birth control implants in women of various ages. In 2018, some 141 girls under 21 years of age obtained the birth control device.

Changing the Chip

You always want what’s ideal: girls not to have sexual relations, but that’s not reality,” says Xinia Obando, general practitioner at the La Cruz public clinic.

Sources consulted for this story agree on a single path to explaining the reduction. In 2015, UNFPA formed an alliance with the Costa Rican Social Security (CCSS) institute and the La Cruz health department in order to expand access to contraception in the canton with monthly injections and, best of all, the birth control implant which the country would offer to adolescents.

The CCSS was planning to expand the availability of contraception for young girls in the Huetar Atlántica and the Brunca regions, but not in Chorotega, which is also facing pregnancy challenges. For this reason, the UN decided to focus on La Cruz.

“We thought of this canton in Guanacaste (La Cruz) which has, unfortunately, been in the top 10 and shows signs of vulnerability,” says UNFPA sexual and reproductive health analyst Evelyn Durán.

While access to CCSS contraception in the Atlantic and Brunca regions was only for adolescents, in La Cruz they provided it to women of all ages because, according to Durán, they didn’t want to exclude anyone.

The choice of these contraception devices was based on sexual and reproductive health surveys (2010 and 2016) designed to understand which method was most used in rural areas. “We reached the conclusion that there was a high number of women who preferred long-term contraception, and for each one that used long-term one, three used injections,” Durán said.

So the UNFPA planned the purchase of 6,900 injections and 450 birth control implants.

Under the accord, the UNFPA and CCSS trained all medical personnel of the seven Ebais clinics in La Cruz in two to three-day sessions throughout 2016 and 2017. They explained the different contraceptive methods, how to insert them and provided advice on family planning. Doctors say they were able to brush up on knowledge.

“When they started training, I said. ‘How am I going to put an implant in a young girl?, but the reality is that teenagers have relations and they are getting pregnant,” says Doctor Obando, who is now collaborates in the training of other clinics in the Chorotega region, such as Liberia and Nicoya, which are beginning to expand the availability of contraception.

Finally, in May 2017 after the training sessions, the Ebais clinics in La Cruz began offering the implants and launching further plans. Their protocol was followed carefully: When a young girl came to any type of appointment, they would talk to her about contraception, the freedom they have to choose the method they want and for it to adapt to their conditions. There was an emphasis, above all, on family planning and how to avoid unwanted pregnancy. In order to access methods here or any other Ebais in the country, children don’t require parental permission.

Director Coronado says they started to announce the availability of the new methods through the Ebais’s loudspeaker.

Marta Bello, Susan’s mother, noticed a difference. “We didn’t use to talk about contraception in the household, not even much in the hospital. That’s why I am more open with them,” she says.

This paints a brighter future for the socioeconomic conditions of the population. A UNFPA study shows that access to contraception reduces the number of children a mom has and that the more children a mother has the more likely she is to live in extreme poverty.

An analysis by The Voice of Guanacaste also showed that the possibility of having a salaried job reduces the likelihood of Guanacastecan mothers having more children. Meanwhile, the more kids they have the less they study in school.

Let’s Talk About Sex!

When they arrived in the canton, the UNFPA formed an alliance with the Network for Children and Adolescence led by the city and made up of institutions like the Public Education Ministry (MEP), the national police, the Health Ministry (Minsa), the CCSS and the National Board for Infants (PANI). The network had already been working with adolescents on issues such as violence, sexual exploitation, and trafficking, self-esteem and family planning.

The network and the UNFPA started holding workshops on sexuality, human rights, leadership and teamwork led by kids from La Cruz. “These people then distributed information to their friends and colleagues and we helped them provide more detailed information on matters that they weren’t fully up to speed on,” Durán says.

They also spoke about sexuality and contraception during talks at high schools. “I explained to the kids that pregnancy means postponing life plans,” says Minsa family planner Noemy Vázquez.

Zaylin Bonilla, a social worker for the local government, believes that kids can build their own future with these types of messages. “They can also break the pattern that they are typically raised with, which is drop out of high school, the boys go to work on a farm and the girls take care of the kids and become housewives.”

It hasn’t been easy. When the idea for implants started to reach the community, other voices arose. Noemy Vázquez remembers it clearly. “They said it was the devil’s tool,” she says.

There was one pastor who spoke of the devil’s chip and that prevented some women from choosing it and accessing their rights,” Durán.

In La Cruz Ebais, Susan said it has become more normal for her friends to talk about contraception and sexuality. “Several of them have the implant, and they talk to us about that here (in the medical center) and also in high school,” she says.

“For people to talk about contraception and sexual and reproductive health also helps women take control of their own sex lives and allows us to make a different decision about how to manage our sex lives,” the UNFPA advisor says.

Little by little, the inter-agency actions are starting to return hope to those who want to continue studying and being teenagers with an immediate future that doesn’t include diapers or cribs. For Susan, it means playing ball and dreaming of becoming an obstetrician. “I’m interested in everything that has to do with babies,” she says, but rejects the idea of having one soon.

Comments