Felip Alegria, 76, sits calmly on a windy May morning to talk with his two friends in the central park of La Cruz. He doesn’t seem too worried about his town. He says it’s peaceful living here, although he recognizes that, at times, there is a robbery, drugs and, once in a while, a death.

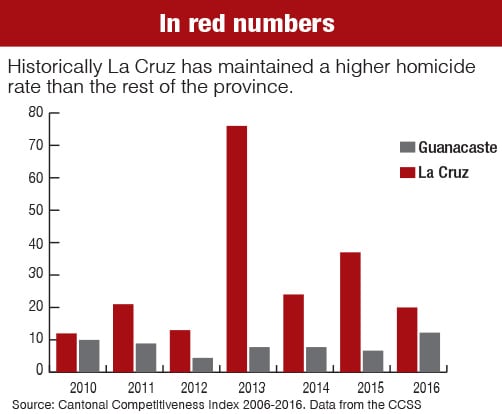

Far from Alegría’s gaze, but in the same canton, a different reality exists in which homicides have been trending upward throughout the past decade.

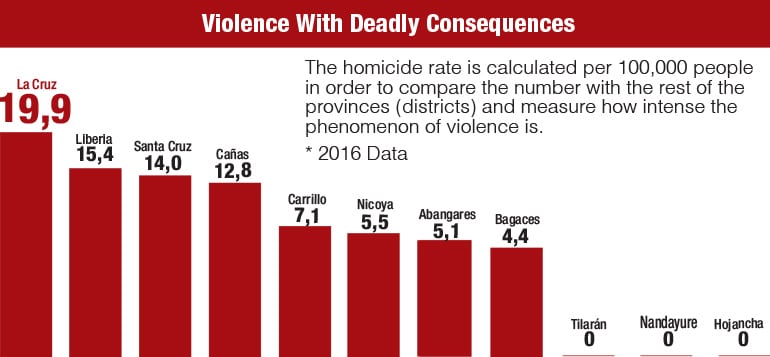

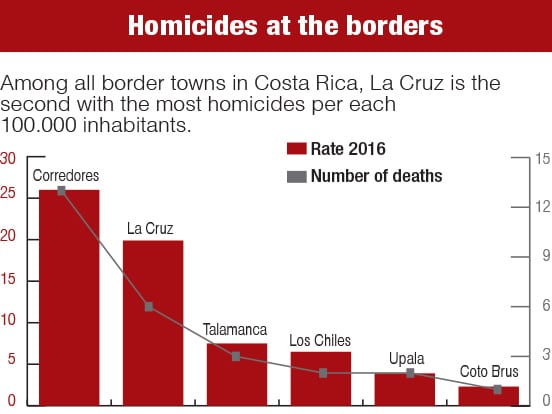

If we use the homicide rate (which calculates the level of intensity of the problem using the base of 100,000 people) La Cruz was the canton with the highest levels in the whole province in 2016 and the second highest among border towns nationwide (only Corredores in the south was higher).

For example, in the last five years, La Cruz had an average of 5.4 murders per year while Liberia had 6.2. The first canton had almost the same number of homicides, but Ciudad BLanca has three times the population. This means that the phenomenon is much more intense in La Cruz.

The numbers come from an analysis done by The Voice of Guanacaste based on the University of Costa Rica’s Canton Competitiveness Index.

According to authorities, incidents don’t happen daily and the majority occur in distant and hard to reach zones without much development. In fact, La Cruz is the second largest canton in Guanacaste in terms of territory, after Liberia.

These conditions make it understandable that a citizen like Alegria sees “the dead” as isolated incidents. But they also lead to the development of activities like drug trafficking, which, according to authorities, is the leading cause of murders in La Cruz.

Numbers in the Red

La Cruz is home to about 19,181 people, according to the 2011 census. That’s few in comparison to other cantons and that makes one homicide weigh more in the stats. In statistics it’s not the same for one person to die in a population of one million versus a population of 19,000.

In order to compare the data correctly among places with different numbers of people, and in order to understand how intense the murder phenomenon is in each one of them, a figure called the rate is used. The murder rate uses the figure of 100,000 residents as a base, solely as a means to standardize the number and make it easier to compare.

In the case of La Cruz, the murder rate has surpassed the number reported for the province and the country in each year of the past decade.

In 2016, while Guanacaste had a murder rate of 10.8 and Costa Rica’s was 11.8, La Cruz reached the highest number of all cantons in the province with 19.9.

How to Understand This

Daniel Calderón, regional director for the national police in Guanacaste, explained that La Cruz reflects the violence that the country is suffering and that it comes from drug trafficking and organized crime.

“The country has seen an increase of these two factors, which has made violence rise nationally,” he said. “In Guanacaste, a canton like La Cruz this problem starts to manifest itself and becomes worse because of its condition as a border town”

Calderón’s assessment is backed by studies. The Interinstitutional Technical Committee on Living Statistics and Citizen Security concluded in 2017 that the increase in homicides nationwide is closely linked to organized crime. La Cruz doesn’t escape this trend.

According to the committee, in Costa Rica only 2.5 percent 2010 homicides were due to the two categories associated with organized crime (revenge and score settling) while in 2016 that number was around 46.2 percent.

In 2017 the national police confiscated more than 55 kilograms of cocaine off the streets of the canton, which, according to Jimmy Araya, the chief of police in La Cruz, is more and more common.

The Weight of Poverty

Adding to the complexity of organized crime are other factors that make violence worse in the canton.

La Cruz mayor Junnier Salazar says that, to a lesser extent, poverty and a lack of education in the zone play an important role in the numbers.

“Poverty makes people look for fast, easy money and that ends up, in some cases, in crime (homicides),” she said.

It is recognized in the country that in cantons such as La Cruz where basic human needs aren’t met and access to education is lower, murder rates tend to be higher.

This conclusion was reached in the study “Territorial patterns and sociodemographic factors associated with homicides and drug trafficking in Costa Rica” by think-tank Estado de la Nacion in alliance with the Costa Rican Drug Institute (ICD) in March 2018.

The Social Progress Index, which tracks the capacity of societies to cover basic needs and provide opportunities for advancement and improving the quality of life of its residents, placed the canton in the penultimate spot among among the country’s 81 cantons. La Cruz is deficient in matters of wellbeing and education.

Slow Response

In order to mitigate the problem, the local government and national authorities are working on strengthening strategies, including the improvement of police information systems that allow officials to get ahead of crimes groups may commit.

Salazar said that the city is considering installing security cameras in spots considered strategic by public security experts. But they are still in search of the funds for this and they don’t have a clear deadline for implementing the initiative.

“I can say that the situation worries,” the mayor said. “I know that this has been happening for years and that more actions should have been taking in the past. But, well, what we are doing is trying to not let it get out of hand.”

Putting into effect more community security programs is another strategy that the policy want to use to fight the problem.

Araya, chief of police for La Cruz, said that they are currently working with 35 organized groups from different neighbourhoods.

“Here, actions need to be preventative,” he said. “We direct police presence according to the complaints we receive and we advocate for having informed communities and other recreational programs for the population so they don’t get involved in drugs.”

The programs that authorities mention are small steps towards fixing a problem in which each number is a life. “But look, we are good people here,” says Felipe Alegria, sitting in the La Cruz’s park, tells me, as if saying that there is still hope.

Comments