The new bylaws limiting construction next to the Ostional National Wildlife Refuge got another green light. The Nicoya city council approved its second publication in the government gazette, La Gaceta. At this time, the plan is in consultation: all neighbors can send their questions to the municipality regarding the new document.

The plan seeks to provide an “environmental cushion” protecting the refuge from noise and visual pollution from buildings (which can disorient turtles and other animals) so animals can roam more freely in the protected area.

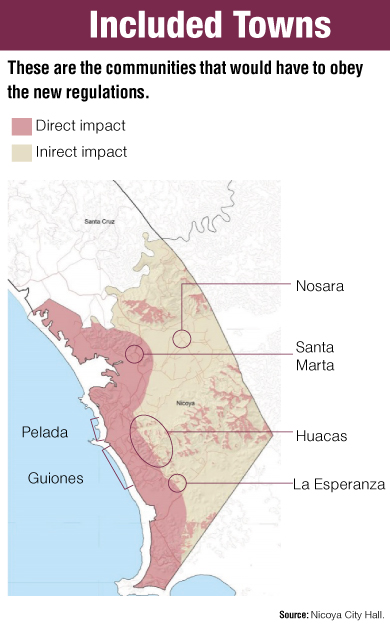

Places like Guiones, Pelada and the town of Nosara are inside the affected area in a 3-mile area divided into two parts, one consisting of a direct impact zone (about half a mile inland from the outer limits of the refuge) and another indirect impact zone, which consist of the remaining 2.5 miles.

In general terms, the council approved limiting construction to 50% of a lot’s total area (and no longer 40% as previously requested). That limit encompasses anything that affects the land, such as a pool, sidewalk, any structure with a roof, etc.

It also restricts the height of buildings to 30 feet in the direct impact zone and 40 feet in the indirect impact zone (roughly between two and three floors).

All constructions must have systems to treat waste water and include measures preventing lights from being visible from the beach. New construction must also prevent birds from flying into buildings.

The bylaws are temporary and will be binding for two to three years, in theory, which is when a new zoning plan will take effect for the Nosara coast, a legal commitment assumed by the City of Nicoya under urban planning legislation.

As of the second publication in La Gaceta, the city opens a space of 10 working days to receive questions and comments. The third publication is final.

In order to understand the economic and social impact the plan may have once final, The Voice of Guanacaste cross-referenced data from different sources on construction and analyzed data on investment in the zone in the last few years, as well as the social progress that these capital injections have brought for the district.

Economic Impact

For those who don’t know, Nosara is a district rich in foreign investment and has coasts that are mainly occupied by tourists and expatriates who love nature and surfing. Native Nosarans live in the towns furthest from the beach.

The elaboration of the plan was contentious and involved activists, developers and all types of residents. Among the criticism is that restricting construction will hurt job and economic growth in the area.

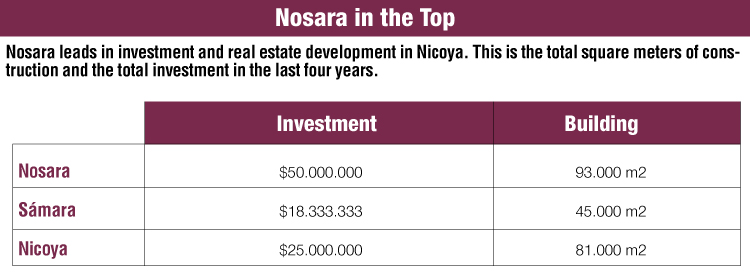

The level of capital injections in construction in Nosara is the highest in all of Nicoya. In the last four years, developers invested $52 million in Nosara, double that invested in the central district, according to the City of Nicoya.

Josué Ruiz, director of the construction department for the City of Nicoya, says the impact on the intention of building will be light since the large part of buildings will be able to be built despite the new limits.

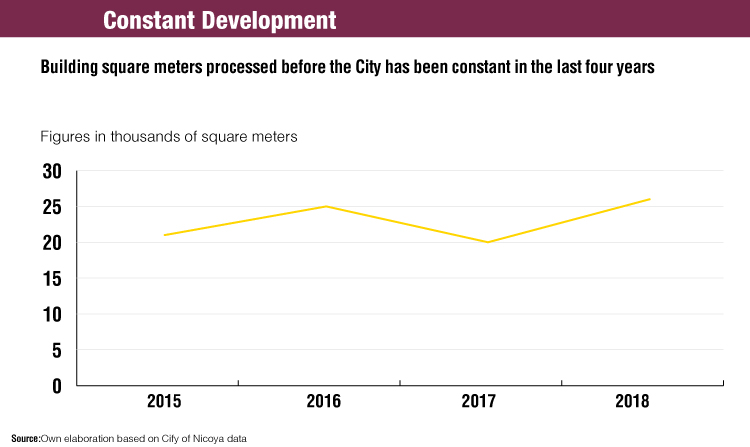

“The average construction project that we have in the city is below the limits we want to impose. There are very few (50%) that pass the limit right now,” Ruiz says. But construction has increased (See chart).

Nosara also contributed almost half of the annual construction permit revenues for city hall, totaling $550,000 in the last four years. But the investments haven’t necessarily lead to development. The Social Progress Index (IPS), applied in Nosara by Incae and Viva Idea, revealed that the coastal district is one of the 10 tourist districts (of 26 analyzed in the country) with the lowest level of social progress. IPS measures the efficiency with which a community converts wealth into development for all.

The turning point for the new bylaws, however, is the protection of the environment. In reality, social development and environmental protection shouldn’t be seperate, says Karen Chacón, a researcher for think tank State of the Nation

“It’s a myth to think that you either protect the environment or create economic development. That’s because we haven’t provided development options for coastal communities,” she says. She means that there should be incentives to promote social development in coastal areas along with the zoning plans.

While the environment has always been a concern to foreigners, Nosarans also feel affected when rivers overflow or dry up in summer.

District representative Marcos Ávila says he is working on a plan to relocate families who live near the river. His biggest concern is that the bylaws hurt his housing project, though he believes that it is below allowed limits.

Ávila’s doubt arises because the first versions of the plan restricted lot divisions to 10,800 square feet in the direct impact area and to 2,700 square feet in the indirect impact zone. The current version eliminates this restriction and only states that lots can be divided as long as only half the property has been built on. If you have a lot of 21,600 square feet you can divide it into four lots of 2,700 square feet, but each lot can only have 1,350 square feet of construction.

The idea of limiting construction is to allow water to filter into the ground and protect water sources.

Was a new set of bylaws necessary?

That’s precisely one of the criticisms from opponents. On July 11, the director of public affairs for CLC Global, Daniel Schuster, said that it’s not necessary to create new ordinances.

Schuster represents opponents to the new rules. According to him, existing bylaws and the lack of water in Nosara already regulate the real estate market.

Chacón, from PEN, says that the habitual regulations such as viability or environmental impact studies required by the National Environmental Technical Secretariat (SETENA) as well as water permits are not enough to control construction in a coastal zone as specific as Nosara.

“The capacity of the lots and the conditions vary from zone to zone in terms of size, population, need to protect water sources and, fundamentally in Guanacaste, where those consequences are already being seen,” Chacón said.

Another question that came up during the drafting of the plan was whether or not construction had increased so much that it was necessary to urgently create limits. The city only offered data between 2017 and 2018.

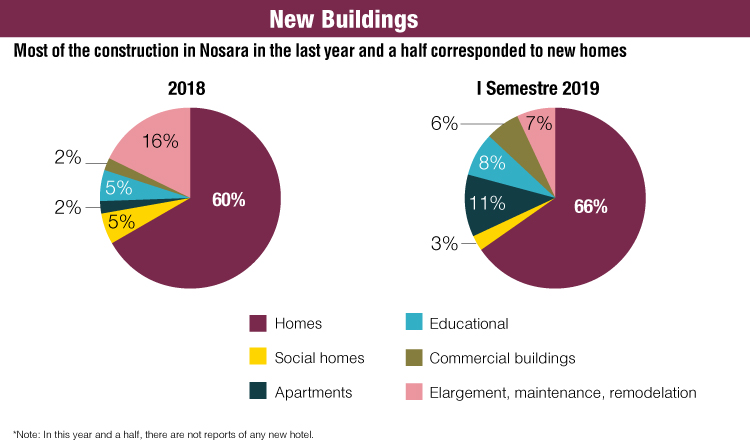

Data from the city analyzed by The Voice of Guanacaste show that the spike in construction wasn’t so abrupt, but it has been sustained over the last several years. In 2015, some 226,000 square feet were built versus 280,000 in 2018 (25% growth). Most of it is new housing (see charts).

Data from the engineering and architectural professional association show the intention to build, which refers to the number of square feet requested that haven’t yet received permits. The data reveals an increase since 2010, when 111,000 square feet were requested versus 327,000 in 2016 with almost constant growth every year.

A Plan with Enemies

Although, according to Josué Ruiz, 80% of the emails received by the Municipality in the first consultation support the plan*, not everyone agrees with the rules published in La Gaceta. Some neighbors say the rules were watered down from the first version of the document and fear for the protection of the forest.

“It saddens me that they haven’t been able to implement the minimum size of a lot because I think one of the worst things that can happen to us is to divide up the lots into very small parts and end up becoming a ghetto on the coast,” says attorney Andrés González, in a video.

Others are entirely against publishing the plan. They believe it to be unnecessary and even illegal.

The two opponents who have shown the greatest concern in meetings, emails and letters sent to the council are former congressman Otto Guevara, who says he owns a lot in Ostional, and real estate broker Jeff Grosshandler, who co-owns and manages the Gilded Iguana. He declined an interview request from this newspaper.

Ex-congressman Guevara sent a report to the council requesting the State’s Attorney consider the bylaws illegal. Considering all the above, the council who drafted the plan decided to change some details and publish it in La Gaceta.

The council’s attorney Gerardo Carvajal, said that the bylaws are part of “precautionary principle” under which nature is protected without knowing whether certain activities will harm it or not. “If there is no certainty that something will create damage, then they opt for protecting it,” he says.

Download here the original data used for this report.

*Editor’s Note: This report was modified with additional information on September 6, 2019 at 2 p. m. No changes were made to the lines already written.

Comments