Petrona Ríos walks slowly. Through the glasses that she always wears, she observes the forest at the Santa Rosa National Park, which is still green in November. “There is one here,” she says as she breaks a branch off a tree. On the other side of the leaf, an almost imperceivable larva feeds.

“Eyes discovering species,” says the embroidery on her shirt from the Guanacaste Conservation Area. That phrase says it all. Some 35 people like her dedicate their days to discovering and systematically recording the species that appear in the ACG. There are around 350,000 different species.

Her profession has a difficult name to pronounce: parataxonomy. But she explains it well.

“We are like paramedics,” she says. “But instead of providing care to someone before taking them to a doctor, we collect and research the bugs before we take them to the taxonomist.”

A taxonomist is a professional who classifies living beings into species, genus, family etc. The term parataxonomist was invented 30 years ago by a biologist in Guanacaste, when Petrona was 23 years old and about to become a secretary or teacher.

A New Hope

“I worked for three years in a fast food restaurant in San Jose while I studied to be a secretary, but I never liked it,” Petrona says. So she returned to find a job in La Esperanza, the town in La Cruz on the slopes of the Orosilito volcano where she was born.

She remembers, back then, that a foreigner came to buy land and preserve it. “People started to say that they weren’t going to let us cut down the forest anymore and that we must follow rules that we had never heard of before.”

During the first few years, landowners like her father thought that conservation was a monster that took over the mountains. Meanwhile, Petrona awaited news from the Public Education Ministry and the Costa Rica Social Security Institute, where she had applied as a professor and secretary.

“A park guard came down the mountain to my house one day with a box full of insects,” she said. “He asked me if I would like to join a project and that there was already a boy from Santa Cecilia working with them.” He told her that it was a very nice job in which you walk through the mountains collecting insects. For Petrona, it was the best job.

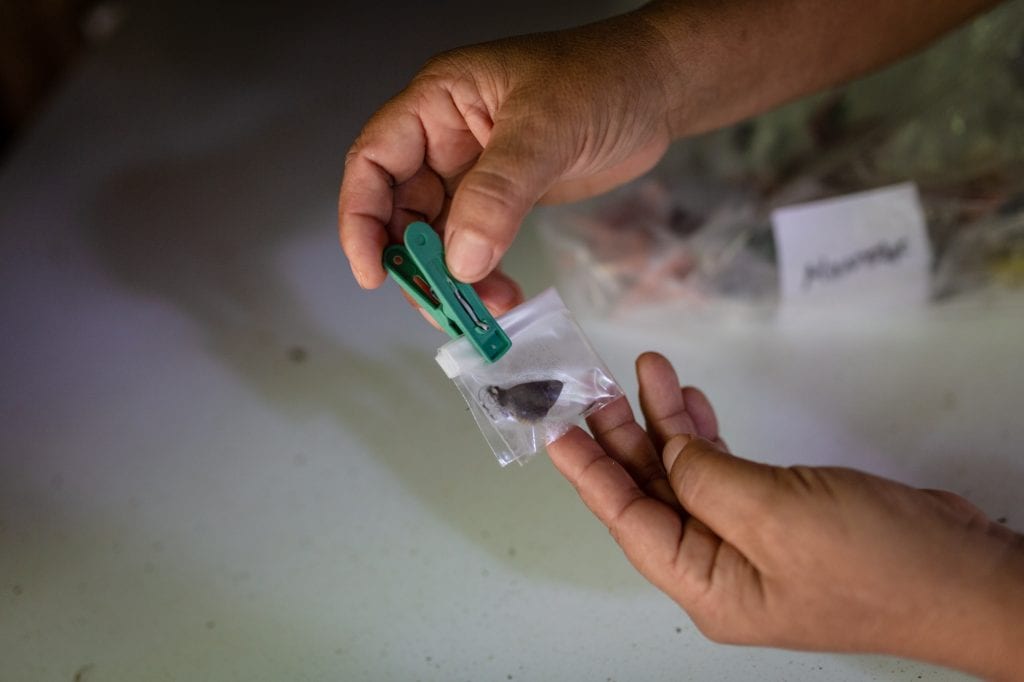

Petrona shows a frozen butterfly. Parataxonomists started a project in 2003 focused specifically on breeding these insects.

Her parents didn’t like the idea. “These people are bad,” they told her, referring to “those people” who prohibited them from hunting and cutting down trees.

They tried to convince her to accept the other jobs that she had almost been guaranteed, but that very summer Petrona decided to become a parataxonomist.

Eyes Discovering Species

In the mid-1980s, U.S. biologist Daniel Janzen started a project to connect Santa Rosa National Park with Murciélago park and Rincón de la Vieja, creating a biological corridor that would connect the coast with the volcanoes. That way he would guarantee that species could safely migrate among these habitats.

But in order to protect it and research the Guanacaste forest, he needed families from neighbouring areas to take charge of caring for it as if it were their own land. He needed people with the desire to work regardless of whether or not they had experience in biology. “Several of us had finished high school, but others barely finished grade school. We are country people,” Petrona says.

Janzen, 80, is the father of the project, her boss and role model. He has won several international awards for his contributions to biology. He works several months a year as a university professor in the U.S, but his house is here, inside Santa Rosa National Park, close to the forest and the parataxonomists.

He introduced the first parataxonomists, like Petrona, to biology and then they later transferred this knowledge to the generations that followed. He trained them to observe the forest and to always walk with their shears, bags and markers to identify plants, animals, insects and parasites.

After this work is done, they input the data into a database with all the necessary characteristics and take a picture. In a single months, they can take 1,500 photos of many different species.

The Last of Their Kind

Ríos and another 50 parataxonomists have been responsible for creating an inventory of thousands of species in the last three decades. Their program is unique in the country. Although the ACG is state-run, the parataxonomists are private employees of a project called the Guanacaste Dry Forest Conservation Fund, which operates with local and foreign donations.

The project has the funds to keep itself going for five more years. “But when Daniel is no longer around, I am leaving too,” says Petrona. She speaks of him with the admiration of a disciple and he of her with the affection for a daughter. She worries that when he is no longer here, financing for the project will dry up for the program that changed her life and the lives of many.

“My dad also changed his views. After I started to work, he got rid of the hunting dogs and we sold 84 hectares (207 acres) of forest for conservation,” she says as we enter the room where the rest of her colleagues register the information of the species that were collected in last few weeks.

She stops next to one of them named Calixto Moraga to watch him work. He is her colleague, husband and father of her two children. “The boy from Santa Cecilia that started with me,” she says with a laugh.

Comments