While Marlene Contreras has in her head an infinite list of things to do, what she thinks most about today is her dance performance tomorrow. Few people know that she is planning to get on stage after five years away, and it’s the last dance she wants to do before having an operation on her spine.

We are in her house, an antique wood structure in the center of the canton that has decorations in each corner and on every table, brilliantly colored dreamcatchers and a wall full of pictures that immortalize her contributions to Costa Rican folklore. Some 47 years ago she formed one of the most long-lasting and iconic Guanacaste folk dance groups, Flor de Caña, which has taken her to dozens of countries.

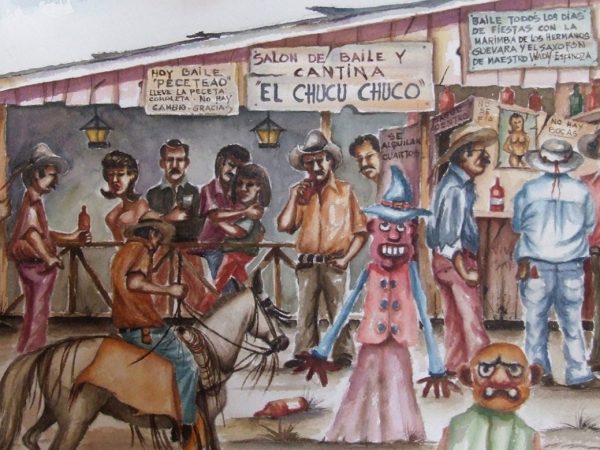

On Saturday, Flor de Caña will close out culture week in Santa Cruz. They will put a punctuation mark on the seven days of masquerades, music, dance, unruliness and all that symbolizes the local and national culture. Santa Cruz is the heart of Costa Rican folklore and Marlene is, for many people, its biggest star.

A friend of mine says that if you don’t know about Marlene Contreras, you don’t know about Santa Cruz,” she tells me with a laugh.

She goes in and out of rooms, opens and closes drawers, checks papers and folds them back up. She says that she spends most of the night at a desk in the middle of the room.

“I don’t sleep much,” she says. “Not much at all,” mummers one of her students in a low, but scolding tone.

She has so many ideas in her head that it keeps her awake. “What I don’t have is time,” I recently heard her tell a friend of hers. She makes the headdresses, the smocks, the bands for the costumes. “I’m up until two or three in the morning,” she says, but doesn’t forget what her cardiologist told her. “I need my sleep.”

She can only do this much by sleeping little. Marlene founded Flor de Caña almost half a century ago and has, since then, built a career as a researcher, folklorist and dance instructor for more than 1,000 dancers in Guanacaste.

The Dancer’s Wound

She makes the headdresses and designs the costumes of her Flor de Caña group. Photo: César Arroyo Castro

Without Marlene having asked me, I’ve been her driver the whole day. It was the only way I could find to get to know such a busy woman.

On the way from the house to the car she tells me that she hasn’t danced on stage in five years and that tomorrow’s performance is in honor of her late mother and the centenarians in the province. That’s why, she says, it’s so important to get on stage at least once more.

As always, she’s thinking about a bunch of different things at once. She moves from one topic to the next. “For me, jeans and tennis shoes are the most comfortable, but I love high heels,” she says all of a sudden. “I got it from my mom.”

It’s impossible to overlook how elegant she is. Well-fitting dresses, bracelets and rings on both hands, three earrings in each ear, false eyelashes and long finger and toenails, perfectly decorated. Who would believe that this restless woman is 69?

“What happens is, when I use heels, my back starts to hurt after a while,” she says, limping slightly. While standing, walking and even sitting, Marlene’s spine looks curved. She says that on top of heels, driving also hurts her back, which is why she doesn’t do it.

As we arrive at one of the day’s meetings, she tells me that the spinal problems started 25 years ago when she and 30 of her dancers were on their way to Melico Salazar theater (in San José) for rehearsal.

“When we were nearing San Miguel de Cañas, the bus lost control and flipped over,” she tells me. “Many of the students broke bones and had deep wounds. One woman lost her eye, a man broke his ribs and my spine was hurt.”

Back then, the consequences for her spine weren’t serious.

It got worse a little bit at a time, until the point when I felt like I couldn’t walk.” Marlene, who had danced since she was a little girl in cultural activities and who was already an icon of Santa Cruz folk dance, felt like she couldn’t walk.

But medicine and “faith” helped alleviate her. “I no longer dance, but I do warm-ups, go to therapy two or three times a week, swim, I walk 12 kilometers per day, I do zumba and I take medication.”

Every January 14 for the last 14 years, she dresses the black Christ of Esquipulas during the town celebration. She prays every time she sits down to eat, tries to go to church everyday and is religious because she’s felt faithful ever since she was a little girl.

Whether it’s medicine, faith or stubbornness, there is something that keeps her on her feet, like today when culture minister Sylvie Durán visited with her entourage and Marlene has been in all the meetings.

A Compelling Dream

At age 101, Enriqueta, Marlene’s mother, told her that she wanted to go, and she stopped eating.

I got very,” she said and paused as though she were looking for the right word in her head. “It wasn’t fear, but I didn’t want her to say that because I didn’t want her to leave,” she says as we walk along the packed, loud streets of Santa Cruz.

On August 4, 2017, Marlene decided to take her to the hospital, but they promptly returned home. Roughly 30 hours later, at 4 p.m, Enriqueta passed away.

Marlene has several dreamcatchers at her house that she has made herself, many religious images and a wall full of recognitions she and Flor de Caña have received. Photo: César Arroyo Castro

But it wasn’t the last time that she saw her. A few months ago, while she was sleeping, Enriqueta appeared. In the dream, she took her to a place with a lot of large photographs with the faces of people who were 100 years old or more.

“I was able to give her everything she wanted and needed, except a large photograph that she always wanted,” Marlene tells me in a sad voice.

In honor of her mother and her dream, Marlene has been preparing tomorrow’s performance for a year and-a-half. Her dancers have helped her collect diapers and celebrate with the centenarians in the province. This is partly because she has a pending debt with her mother and partly because she doesn’t do anything without previous research, and this was her way of getting to know them better.

Sudden Doubts

It’s nighttime in Santa Cruz and Marlene and I arrive at the final rehearsal at the Espíritu Santo (Holy Spirit) School. There are 50 dancers of all ages coming and going in perfect coordination. Around the gym, some parents brought comfortable beach chairs while they accompany their kids.

Marlene sees them, analyzes them and gives some instructions. Then she takes a few minutes to practice her part, discreetly, without music in the background.

With her dance partner, they rehearse what appears to be a bolero. She moves a foot forward, the other back and when she has to spin around her partner, she fails. Her partner stops, explains how to do it and tries again. She looks concentrated, but fails again. She has a look of obvious concern on her face.

After the rehearsal, when we get to her house, she tells me something unexpected.

I don’t know if I can dance or not. In order to do that, you have to prepare yourself psychologically. If I don’t feel right, I better not do it.”

I left that day without knowing whether or not she will take the stage. She didn’t know either.

Final Day

It’s eight o’clock at night and Flor de Caña takes the stage. One, two, three and even four dances. Marlene, in a semi-hidden corner of the stage, tries to make sure everything goes right with the sound, images and movements of her students.

I might be the only person in the audience that is waiting for Marlene to take the stage and pay tribute to her mother, the centenarians and her half-century-long legacy. But Marlene Contreras, “the great master of Costa Rican folklore,” as singer Guadalupe Urbina called her, decides not to dance.

At the end of the presentations, Flor de Caña dancers took the audience to the stage to dance. Marlene was one of those. Photo: César Arroyo Castro

I saw her a few days later at her house. Outside a crowd gathers as they make their way to the Santa Cruz rodeo. She’s wearing jeans with a row of beads along the leg, a white blouse and, of course, high heels.

I ask her why she didn’t dance. “I felt like I was going to cry a lot. I didn’t feel strong,” she says as though she had a list of reasons ready. “I don’t want to do something stupid. If I’m going to look bad and tremble, I’d rather sit. That’s the way I see it.”

She doesn’t look concerned. She doesn’t have the face of someone who has missed what could be their last opportunity to get on stage. She’s not worried about the spine operation. I keep asking her how and why, but she makes it clear to me, “I have faith.”

Comments