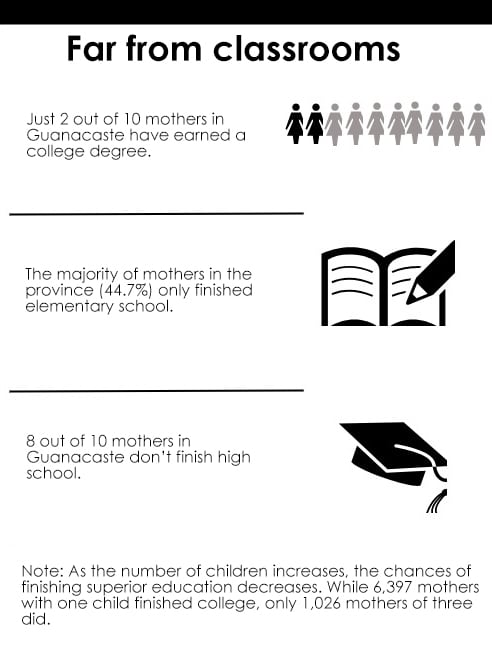

Eight out of ten mothers in the province don’t graduate from high school. Less than half finished elementary school. On the other side of the spectrum, 17% got a college degree.

These data come from an analysis by The Voice of Guanacaste on the characteristics of Guanacastecan women who are mothers and live with their children (see sidebar). The data were extracted from the National Survey of Households in 2016, which was done by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (in Spanish, INEC).

The data show that as the number of children increase, the chances of finishing higher education diminish. While 6,397 women with one child finished university, 1,026 did so as mothers of three.

Greylim Matarrita had Samuel when she was 25. Back then she hadn’t graduated from high school and worked informally. Her desire for a better future for her son was the motivation she needed to return to the classroom. Today she’s nearly earned her technical degree. With the help of her mother and stepfather, and without the help of the child’s father, this resident of Pozo de Agua is getting plans together for what will be, in just a few months, her own home.

Eight out of ten mothers in the province don’t graduate from high school. Less than half finished elementary school. On the other side of the spectrum, 17% got a college degree.

These data come from an analysis by The Voice of Guanacaste on the characteristics of Guanacastecan women who are mothers and live with their children (see sidebar). The data were extracted from the National Survey of Households in 2016, which was done by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (in Spanish, INEC).

The data show that as the number of children increase, the chances of finishing higher education diminish. While 6,397 women with one child finished university, 1,026 did so as mothers of three.

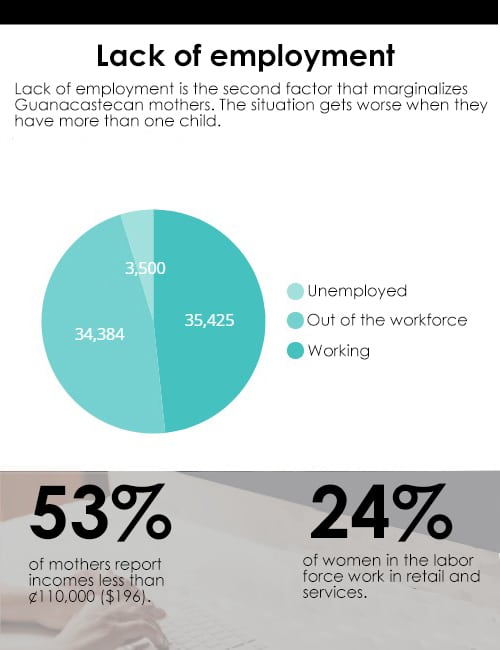

Along with low levels of education, more than half of Guanacastecan women suffer from a second marginalizing factor: lack of work. 51.67% of mothers are unemployed (don’t have a job, but are looking for one) or are out of the workforce (not looking for a job, even though they are of working age). These numbers get worse as you add children to the home.

Heylin Rivera could have had a much simpler life, but she wanted more. Her character brought her to challenge the machismo that surrounded her, she says, within her family, and set goals that would truly define her. Life listened and when she was 18 she had her only child, Diego, who was born with cerebral palsy – an even greater challenge. With constant help from her inner circle, she earned a degree in educational IT. She has had to travel from Nicoya to Poás de Alajuela every week for more than 13 years to see Diego on the weekends after she won a tenured position with the Ministry of Public Education (MEP). Today she works in Central School in Carmona de Nandayure and says that, at 36, her life has just started. Seeing that Diego is a step away from getting his high school diploma and dancing traditional dances confirm it.

This isn’t just a problem for single mothers, but across society: with little education and removed from the labor market, household incomes are affected and, in turn, communities prosper less.

A little more than half of mothers in the province (53.71%) report incomes less than ¢110,000 – less than minimum wage.

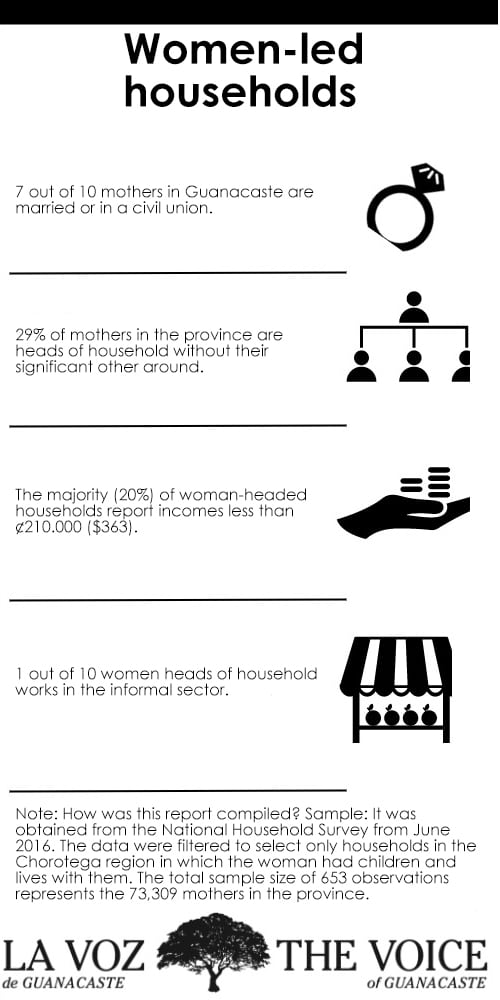

This statistic becomes more worrisome if we add that in Guanacaste four out of 10 women are heads of household and nearly all of the heads of household (71%) do not have a romantic partner to help out.

It’s one thing and another and another

How can we explain this situation? Melida Carballo, regional coordinator for the National Institute for Women (INAMU), says that the simple condition of being a mother sets them apart from the educational system and labor market.

In Greylim’s case, her mother watches Samuel, sometimes from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m., while Greylim combines her job as a clerk with her studies.

But that’s not everyone’s good luck, says Carballo.

If she’s a teenager and gets pregnant, she’s taken out of school due to the culture of punishment. The saying goes, ‘better to stay at home than to play in the street,’” she says.

Machismo manifests itself in domestic violence, which is another obstacle for mothers who want to get an education.

Experience tells Carballo that women who have a Guanacastecan husband or boyfriend have to work twice as hard to go to school due to the patriarchal culture that reigns in this region.

In fact, The Voice of Guanacaste showed that the rate of domestic violence against Guanacastecan women is 38% higher than in the rest of the country, according to statistics from the Observatory of Gender Violence Against Women from the Court System. Attempted murder of women is also highest in Guanacaste.

Her most popular role is the presidency of the Nicoya Municipal Council, but Karen Arrieta has stood out in all the non-traditional roles she’s undertaken. She was an honor student at the Technical University of Costa Rica (TEC) in construction engineering and also served as the director of the Technical Unit of Roadway Management for the Municipality of Nandayure. When she was just a few courses away from graduation, she got pregnant with Mariano. This did not become an obstacle for her; she finished her studies and continued being a mother and leader at the same time, because those two words aren’t a contradiction.

An education that doesn’t address the reality of these mothers and state-sponsored solutions that miss the mark end up clouding these women’s educational possibilities.

What can we do?

It’s not all dark. The dean of the local campus of the Universidad Nacional (UNA), Olger Rojas, says that institutions should think about childcare spaces if they want women and mothers on their list of students; solutions are born of the problem.

In the case of UNA, Rojas says that the majority of students at the Liberia and Nicoya campuses are women.

The University works in conjunction with the Children’s Centers of Comprehensive Attention (CEN-CINAI) in these cantons to attend to the children of mother university students during classes.

In the future, UNA hopes to bring the CEN-CINAI onto their premises so that mothers don’t have to travel as much.

“We also have a sliding tuition scale in which women with children can set their schedules. We also have breastfeeding rooms for students who are mothers. We’re looking for a comprehensive solution,” said Rojas.

Programs like need-based scholarships, sexual education from an early age, and programs on gender roles and female empowerment are thought of as goals the province should reinforce if it wants better results.

Even if women like Greylim take the initiative to study in spite of all the obstacles, for the burden not to be born only by mothers the system must adapt to them and promote a change in culture and thought both in men and women. It isn’t easy, but we have to start.

“The women of Guanacaste are courageous and want to improve themselves and do great things. Most cases have this vision of pushing forward,” said Carballo.

Comments