The 6-inch (15-cm) swab is inserted into one of my nostrils deep into my nasal cavity. Against all bodily instincts, I contain the urge to sneeze or intervene to get it out as quickly as possible. The doctor moves it around for about 10 seconds before removing it. It feels like an eternity. I take a quick breath and on to the next nostril.

If you’ve had a coronavirus nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab test too, you’re familiar with the discomfort that I’m talking about. But that could change for our country with the approval of processing saliva to detect COVID-19.

A group of researchers from the Costa Rican Agency for Biomedical Research (ACIB- Agencia Costarricense de Investigaciones Biomédicas), located in Liberia, wants to validate this method that is already used in countries such as the United States, Germany, Australia and Japan for the Ministry of Health.

It’s not new there [in those countries], but what happens? A national demonstration that this technique or sample is valid is required,” explained the study’s main researcher, Bernal Cortes.

In addition to being less invasive for the patient, the saliva test has a couple more advantages: medical personnel don’t have to be exposed while taking the sample and it saves some resources, such as swabs, personnel taking the sample and the protective equipment they would need to use.

The procedure promoted by the ACIB, however, doesn’t mean faster results because, just like the swab samples, it goes through the real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis.

The ACIB study isn’t the only one being carried out in the country to look for alternative ways of detecting COVID-19. The University of Costa Rica (UCR), with support from the Technological Institute (TEC) and the National University (UNA), is also developing a methodology using saliva to identify the illness.

It’s called RT-LAMP and it makes it possible to get results in less than an hour without sophisticated equipment to analyze the saliva sample. Each saliva sample is heated to 95° Celsius (203°F) and changes color depending on the result: yellow if positive and red if negative.

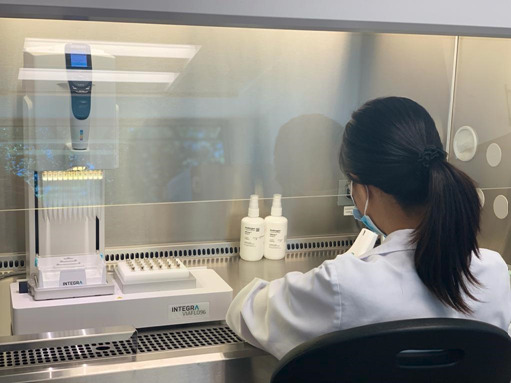

UCR is also investigating the detection of COVID-19 in saliva through a process called RT-LAMP, which makes it possible to get results in less than an hour without sophisticated equipment to analyze the sample. Each saliva sample is heated to 95° Celsius (203°F) and changes color depending on the result: yellow if positive and red if negative. Photo: Karla Richmond, University of Costa Rica.

VALID

ACIB began the study that they call VÁLIDO (VALID) in January. The study calls for taking saliva samples from 100 infected people and 100 healthy people— all more than 18 years of age. At this time, they still need to sample about 50 people who have recently been diagnosed (within one to five days).

If you, a family member or someone you know has just been diagnosed with COVID-19 and wants to participate in the study, just call 2668-1128.

The study researchers will visit the participants homes and take a saliva sample and a nasopharyngeal swab sample from them. Each sample— both the saliva and the nasal swab— goes through the same PCR analysis.

That way we can compare saliva with swab and present the results to the Ministry of Health to become validated as a laboratory that can perform PCR but on a saliva sample and not just on a swab,” explained Cortes.

Is a saliva sample reliable?

The accuracy of the results of the saliva test can vary depending on the point during the infection when the sample is taken and the type of processing, especially for false negatives.

So far, scientific evidence indicates that the viral load in saliva is sufficient to have a positive PCR result after five days, the same as with a PCR swab, explained Juan Jose Romero, an epidemiologist from UNA who is part of the university research team that is also studying saliva samples but with RT-LAMP processing.

According to the epidemiologist, the saliva processing in PCR should have an identical result to that of the swab. “However, there are very few studies that compare them. That’s why ACIB wants to do it,” he pointed out.

With RT-LAMP, a sample taken after the sixth day of infection has very similar results to PCR, Romero said. “But it turns out that precisely because there are a little bit less viral particles in saliva than there are in the nasopharyngeal fundus, it’s possible for there to be more false negatives in the LAMP, about 8-10%,” he added.

According to his criteria, the LAMP test on saliva is intended for use in large screenings, with the advantage that each one costs between ¢6,000 and ¢9,000 ($10 or $15). “But negative results highly suspected of being false negatives would go to PCR,” he acknowledged.

For Research and Social Purposes

With the results of the VALIDO study, ACIB doesn’t intend to sell the PCR analysis of saliva to the general population since it’s a non-profit agency. The researchers’ plan is for their laboratory in Guanacaste to have the approval for analyzing COVID-19 in saliva to continue researching and fighting against the sickness.

In fact, they’ll store part of the saliva samples taken for the study in order to make them available to other researchers who also want to validate their own tests to detect the coronavirus.

They are also interested in offering them for social purposes.

“We are interested in offering a testing service to organizations or groups. Like what?” the researcher explained. “In schools, for example, it would be very good to offer analysis using pools.”

By pools, Cortes was referring to a process in which they take saliva samples from several people and analyze them collectively. “In the pool, what I do is, instead of analyzing them one by one, I test a single sample of mixed saliva and, if they are negative, I only did one test. I saved time and resources,” he explained.

Vaccination and… More Tests?

According to data as of March 1, 2021, health personnel across the country have already administered 149,812 doses of the vaccines. In the Chorotega region, 12,595 have been administered, which is a vaccination rate of 2.7 per 100 inhabitants.

However, the country’s authorities and the World Health Organization (WHO) have said that the vaccines don’t guarantee that the pandemic will end because, on the one hand, it will take time to reach herd immunity and, on the other hand, it’s still possible for a vaccinated person to contract and transmit the virus.

Even when the vaccines start to protect the most vulnerable, we won’t achieve any level of immunity in the population with herd immunity in 2021,” explained WHO scientist Soumya Swaminathan at a press conference in January.

Cortes highlighted another important point: “We don’t know how long the vaccine protects for.”

The ACIB researcher recognizes the importance of various entities conducting research to fight COVID-19. In addition, he has a conviction: “We are next to the Franklin Chan laboratory and, like them, we share the belief of doing technology and science in Guanacaste.”

Comments