El Coco ocean view: Who pays the price for real estate development?

For Sale. Modern luxury house, 138 square meters (1485 square feet), with terrace area and infinity pool. Three bedrooms, three bathrooms. High-quality materials, French doors, chef-inspired kitchen, large windows. Gated resort community with private beach club. Ocean view.

Its price: $1,100,000 USD. That’s the equivalent of 300,000 hours of work for a construction laborer or a cleaning employee, two of the main job options offered by residential real estate developments in this area. About 33 entire years of nonstop work, assuming the body could survive without a second’s rest.

There will be some external costs, but the buyer won’t have to pay out of pocket for them: pressure on already depleted aquifers, environmental impact, segregation of residents, higher cost of living, and increased crime as a result of accelerated urban development.

Welcome to Playas del Coco, the perfect town to live in with your family. That’s how it’s worded in English in dozens of ads printed about sales of villas and condominiums on the coast of Guanacaste.

***

In recent months, the word “gentrification” has been appearing more frequently in the media worldwide. The term refers to the process of urban transformation of a community that causes the displacement of poor or middle-class people and the arrival of others with more financial resources.

It’s not something that happens overnight. It begins with new real estate agents showing up and the construction of luxury buildings. Buildings that are out of reach for the area’s original residents, who end up concentrated in cheaper neighborhoods.

Gentrification began to be studied in urban and central areas, but the phenomenon can also be seen in places with great tourist potential, such as Playas del Coco.

It’s “the domination of the city by high-income consumers who end up displacing the original population, which witnesses the loss of its own residence space.” That’s how gentrification specialist Agustín Cócola Gant described it in 2015 for the organization Alba Sud, which analyzes the impacts of tourism. Although the organization was formed in Barcelona, it has researchers that analyze the problem in Latin America.

Researcher José Arturo Silva, also from Alba Sud, explained that social and ecological conflicts are some signs of gentrification and that the examples are right there, in some coastal areas of Guanacaste.

After immersing ourselves in the stories of these towns, The Voice of Guanacaste has prepared this report to expose the impacts of real estate development linked to tourism in Playas del Coco, Panama Beach, Marbella and Brasilito. Disputes over water, the death of corals and social inequality are part of those effects. In some communities, gentrification is just emerging, but in others, it began to take shape decades ago, when the Costa Rican government opted for the Gulf of Papagayo Tourist Pole (Spanish acronym: PTGP) as a development model in the area.

This is the first installment of a special project by The Voice to understand the inequalities on Guanacaste’s coast.

***

It’s midday on Friday in Playas del Coco and the streets are bustling. There are giant palm trees, signs, tourists, hotels, condominiums, sand, more signs…

Over on a little hill, there’s the luxury house with a chef’s kitchen and a gated neighborhood that the ad offered. Along the side of the road, signs announce more properties. For sale is announced everywhere. Information on the Internet will later confirm the wide range of prices, but all of them cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. “$995,000, just 200 meters from the ocean, in the most privileged area of the city,” says one web page.

Real estate advertisements leave out– for obvious reasons– the province’s problems of access to water, inequality rates and environmental conflicts. But all these details are impossible to ignore here, in this town full of contradictions, with its mix of the pompous and the sparse, where narrow dirt roads run into paved main roads as if by accident and where old wooden houses, frozen in time, resist being turned into condominiums with soaring walls and tile roofs.

Playas del Coco, in the district of Sardinal in the canton of Carrillo, is one of those coastal communities in Guanacaste where urban development and tourism are growing like wildfire, but not meeting the needs of everyone equally.

Carlos Eduardo Méndez peeks out the door when he sees a couple of journalists approaching. He wasn’t expecting us. He runs to put on a wrinkled shirt and serves his mom’s lunch. “Just a moment,” he asks us.

He arranges a couple of plastic chairs in the dining room and pulls at his shirt to fan away a little of the heat of this coastal afternoon. He tells us that he used to be a fisherman, has lived in Playas del Coco all his life and is a fan of landscape photography. And then he explains to us that in Playas del Coco, there are some imaginary lines that divide the community into segments. It would be impossible for any visitor to pinpoint them, but not for him.

If we go to El Coco’s downtown, we find a highway, a central artery, where there are businesses, banking entities. You enter what’s known as La Chorrera and it’s a totally different sector. There, it’s practically sources of work, hotels, restaurants. It’s something else.”

A look from above– with the help of satellite images– helps us to complement Carlos’ description: tiled roofs and swimming pools on one side. Rusted metal roofs on the other.

“You’re going to find a divided class in Playas del Coco,” adds Carlos, “those who are economically strong: gringos, Canadians, Europeans; and those of us from the town, in another class of El Coco, for example, in Las Palomas, El Precario, San Martín and Los Canales, where the coqueños (people from Playas del Coco) live.”

The difference, according to him, is noticeable even in where people make their purchases. “The classes of those of us who are poor go to Megasúper, and the latter classes have Automercado.”

He and his mother, an elderly woman who is 80 years old, live in the Chimbolo neighborhood and from their patio, you can smell the ocean. The house is small, made of wood, with faded paint and a narrow corridor. His mom has always lived there, but it isn’t hers because it’s in the Maritime Land Zone (Spanish acronym: ZMT), which belongs to the State.

The ZMT is a strip that begins at the last line left by high tide and ends 200 meters inland. The family has a concession there, for which they pay the municipality ₡120,000 or ₡150,000 (about $220 to $275 currently) per year, Carlos calculates. This includes the usage fee and garbage collection taxes.

It might seem like a small amount, but not for Carlos, who gets ₡300,000 (about $550) every month in rent from another house that his father inherited and juggles that to cover his and his mother’s expenses. He stopped fishing to take care of her.

The Chorotega region, where Guanacaste is located, has the highest level of wage inequality in the country. In this region, 26.4% of households are in poverty and the average monthly income per person in a household is ₡366,000 (about $670). In Costa Rica, the minimum wage is ₡330,000 (about $600). Carlos and his mother together subsist on less than those amounts.

Carlos has seen other residents move away who had settled there long before the real estate developments. There used to be rural commerce and dozens of modest houses, he recalls. Some were removed by the municipality about 15 years ago because they invaded the public zone, which is the first 50 meters of the ZMT, where building is prohibited. Others who lived in the restricted zone– in the remaining 150 meters, where Carlos lives– accepted tempting offers from investors and gave up their concessions. They left El Coco or moved to other streets more inland and spent the money, which wasn’t much either, he deduces.

Some locals have benefited from the sources of work created by tourism and urban growth, but Carlos doesn’t believe that they are the majority, because people also come from other parts of the country and even immigrants, mainly Nicaraguans, looking for work.

Other Playas del Coco natives still dedicate their time to traditional fishing, an activity at which they can earn nearly ₡300,000 a week (about $550) in high season, but in low season, barely around ₡5,000 (about $10), he says.

Carlos isn’t really concerned about the growing number of foreign tourists arriving who settle for long periods of time or even stay in El Coco. What he is outraged by is that the government doesn’t give the same attention to all the inhabitants, especially when it comes to access to health care or security.

For example, there,”– he points with his chin towards what he calls “the other Playas del Coco”– “they have their own security posts, their private police. Here, it’s the civil guard and it’s totally limited.”

And then, in a voice that’s almost a whisper, he says, “Now there are a lot of drug traffickers. That hurts me.”

Real Estate Explosion

If we were to apply brutal honesty to Guanacaste’s coastal real estate ads, we’d have to include terms like gentrification, inequality, and overtourism.

Researchers use those terms to describe the sentiment of Carlos and residents from other communities along Guanacaste’s coast, as well as environmentalists, with whom we spoke for this report.

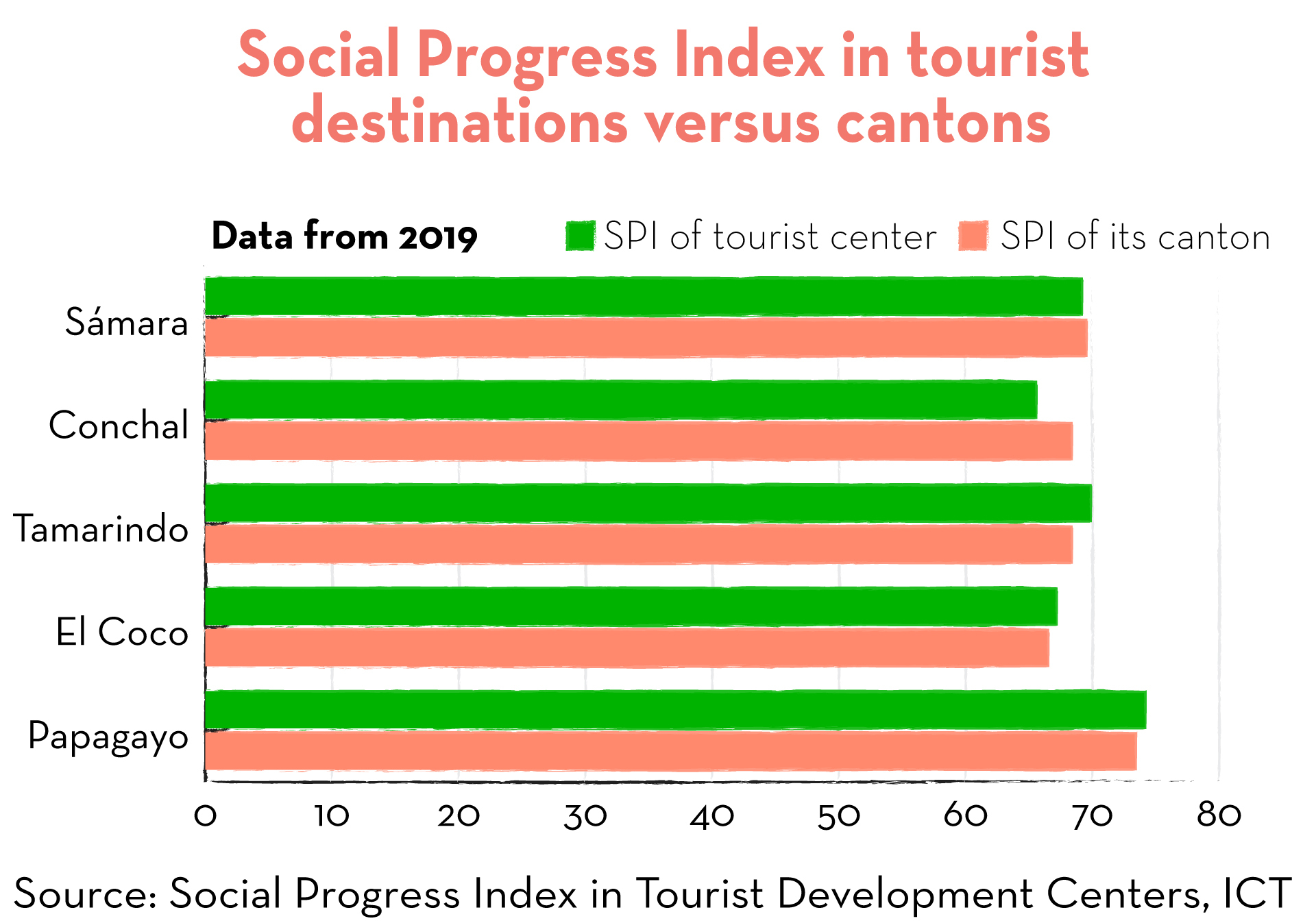

An ad that’s closer to reality would also say that, in the most recent Social Progress Index (Spanish acronym: IPS) done by the Costa Rican Tourism Institute (ICT) on the 32 Tourism Development Centers throughout the country, El Coco is ranked in third place…but from bottom to top. Its IPS is just slightly higher than the average for its canton, Carrillo, which is also in the red (67.23 and 66.54, respectively).

This index measures human development from three dimensions: basic needs, foundations of well-being and opportunities. The results are useful for the State to create programs that promote social progress and inclusive and sustainable economic growth, according to the Ministry of Tourism.

In addition, the advertisements would also explain that Carrillo is below the country’s average in the Human Development Index adjusted for inequality. And something similar occurs in the Sardinal district, which, despite being the least unequal in the canton, shows a significant disparity in personal income, according to data provided by the State of the Nation.

In other words, it’s the same thing that Carlos explained to us: There are two completely opposite ways of life in Playas del Coco.

The canton of Carrillo is 248 kilometers (154 miles) from San José. It has around 37,000 inhabitants and its most populous district is Sardinal. In addition to Playas del Coco, this district has some coveted beaches in the province: Matapalo, Hermosa and Panama.

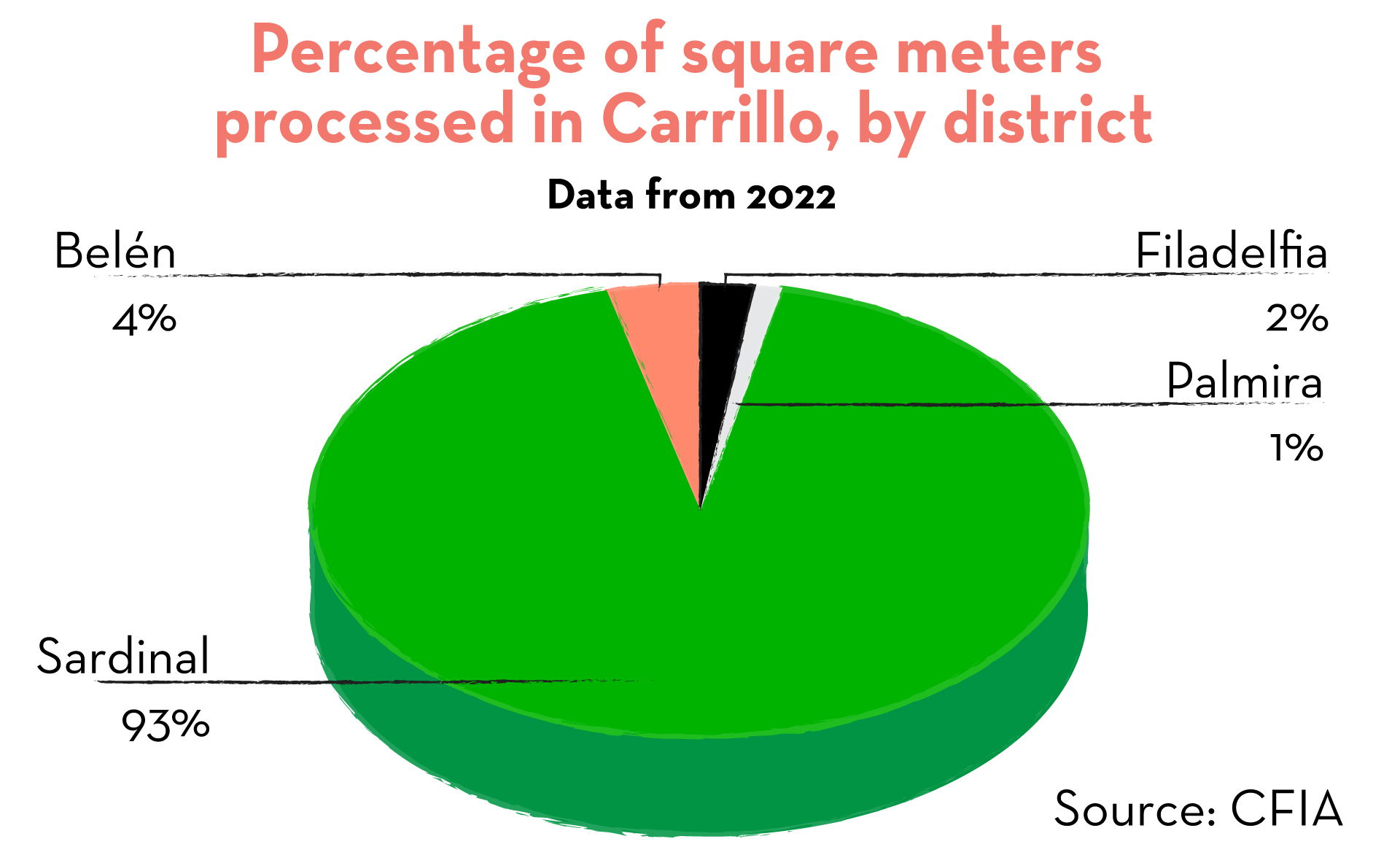

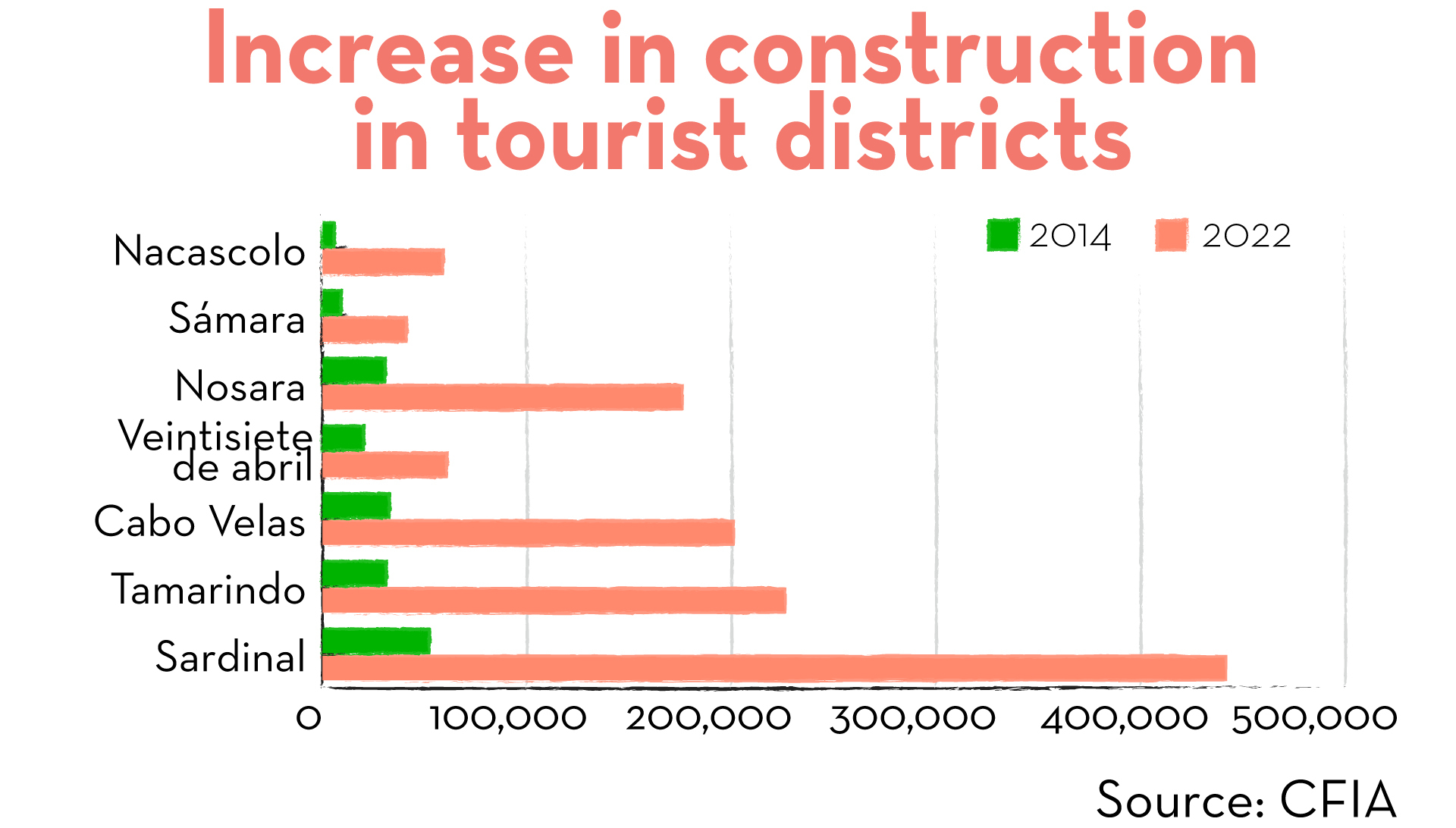

While in 2014, permit paperwork was processed with the intention of building a total of 52,300 square meters (562,952 square feet) in Sardinal, last year, it skyrocketed to 441,700 (4,754,419 square feet), an increase of almost 750% in less than a decade, according to data from the Federated College of Engineers and Architects (Spanish acronym: CFIA). Most of these procedures corresponded to urbanizations and condominiums.

As a point of comparison, in the other three districts that also belong to Carrillo, last year, intended construction did not exceed 20,000 square meters (215,278 square feet) in each one.

With these statistics, Sardinal is positioned as the coastal district of Guanacaste with the second highest real estate growth in the last decade, only surpassed by Nacascolo (in the canton of Liberia), where part of the Papagayo Tourist Pole is located. Although in terms of total construction, the difference is still abysmal, since intended construction in Nacascolo last year was 59,000 square meters (635,070 square feet).

Hot on the heels of Sardinal are Tamarindo and Cabo Velas, in the canton of Santa Cruz, and Nosara, in Nicoya.

Data requested by The Voice of Guanacaste also shows that of the 1,811 active business permits in the Municipality of Carrillo, more than half are from the district of Sardinal.

Beach Houses

Real estate and tourism development isn’t a problem in itself for Guanacaste or for the country. In reality, the tourism industry is the goose that lays the golden eggs, as many people call it. Before the pandemic, it came to represent up to 8% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) annually if both the sector’s activities and the income it generates in other related areas are considered. That’s more money than the country receives for exporting any of the agricultural products that drive the Costa Rican economy, such as coffee, bananas or pineapples.

However, the growth of tourism and urban development in Guanacaste has consequences, and gentrification is one of them, explains sociologist and researcher José Arturo Silva.

For years, Silva has been dedicated to documenting, analyzing, and denouncing the problems associated with the tourism model in Guanacaste. In his opinion, gentrification on the coast is mainly linked to tourism “of second homes for new inhabitants” in beach areas. These are houses whose owners don’t live in them all the time, but they have it at their disposal when they want to come to spend a season there or rent it out.

According to the sociologist, before the arrival of these new residents, “a very dynamic, very aggressive real estate market” is activated, which, with luxury buildings and marketing strategies, targets buyers with much higher incomes than those who historically live in these communities.

The coastal communities in this country, starting in the 80s, have certain economic and labor deficiencies, which to a certain extent could serve as a breeding ground for these changes in land use to be carried out more quickly, with more violence,” Silva explained.

In practice, it happens more or less like this, according to his description: In a first stage of investment, a developer buys properties at a price of $1 per square meter. The following week, that same square meter can be sold for $500, $600, $2,000 or even $5,000. So, without regulation. This occurs in the incipient stages of gentrification, says the researcher. He has observed it specifically in Marbella.

The researcher has identified a greater degree of “real estate maturing” precisely in places like El Coco, Tamarindo and Nosara.

“Where were the first conflicts related to tourism development in the province? In Playas del Coco and in Tamarindo. I’m talking about the first decade of the 21st century,” said Silva, referring to events that marked these communities, such as protests against overexploiting aquifers.

In these communities, it’s clear that environmental conflict is an indicator of gentrification. Later, other towns like Marbella, in Santa Cruz, began this cycle of conflict.

“In communities like Marbella, you can identify sales of lots at a price that’s even laughable [because of the high cost] for the type of market that exists in Guanacaste,” he described.

But maturity isn’t easy to show with conclusive numbers. The Chamber of Real Estate Brokers lacks statistical records on the variation in land prices on the Guanacaste coast, according to responses by telephone.

Nor can we trust the values per square meter established by the Ministry of Finance for collecting municipal taxes, as some are well below market value.

For example, the highest appraisal (value) recorded on the municipal map for Playas del Coco is 250,000 colones (about $460) per square meter, and it’s in the heart of the commercial area. In other points where there is luxury real estate development, values of about ₡80,000 (about $150) per square meter are recorded. A 100-square-meter (1076-square-foot) piece of land in one of those “prosperous areas” would cost ₡8 million (about $15,000), according to those parameters. Something hard to believe when the figures are contrasted with reality.

So the only possible references to get an idea of how the real estate market behaves in coastal communities are the advertisements that circulate on the Internet.

Recently, El Financiero published results based on a review of classified ads on the site encuentra24.com. In Nosara, they charge an average of ₡2 million (about $3,700) per square meter to get a house.

If we do the same exercise for Playas del Coco, the average for buying a home is almost ₡700,000 ($1,300) per square meter, but it’s also possible to find houses for up to ₡2 million per square meter. Also, there are properties that are only posted on other websites or that have their own pages, in English, especially aimed at foreign audiences.

There is no history available on the variation in rental prices in these areas either, nor is there sufficient data on Encuentra24 to apply the same formula.

Carlos, the retired fisherman, only nods when we ask if rents have gone up in the area.

Clearly. Well, I rent [the house that his father left him] for ₡300,000. I tell the man: ‘If you don’t have it, we’ll reach an agreement. You eat and I eat. We settle it.”

The information available at the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (Spanish acronym: INEC) doesn’t permit discerning the difference in the cost of living between districts. This variation can only be observed between rural and urban areas. Statistically, the basic food basket is cheaper in rural areas, but in the mosaic of inequalities and contradictions that some coastal communities have become, it can all depend on which supermarket you choose, says Carlos.

Development that Doesn’t Meet Needs Evenly

In addition to the persuasive advertising of luxury hotels and second homes in the country, Costa Rica has added legislation to attract foreign investors and tourists.

A few weeks ago, for example, the government signed a regulation to simplify bureaucratic procedures for investors, residents and pensioners. The idea is to make it easier to continue with their investments and do their business, according to the Bureau of Immigration.

The regulation establishes the conditions that regulate this category of foreigners who have investments of more than $150,000. Preferential windows for these applications are also established in the General Bureau of Immigration, completely preferential treatment if we consider that, recently, refugee applicants in Costa Rica had to sleep on the street in line to wait to complete their process.

In addition to these VIP conditions for investors, there’s the Digital Nomad Law, approved in 2021 with backing from the administration of Carlos Alvarado. That legislation created a special non-resident visa with a term of up to two years for remote workers, among other benefits.

Sociologist José Arturo Silva explained that there are two lines of analysis on who causes gentrification: one points to tourists and the other to “the producers of space.” The latter includes real estate developers and officials.

“I adhere to the second idea,” said Silva, who points out two main public institutional players that should regulate the real estate market: the municipalities and the Institute of Aqueducts and Sewers (AyA).

“Municipalities have to do with construction permits and, in good theory, you can’t build if you don’t have water supply availability. So there’s a double game of what comes first, the water or the permit,” Silva pointed out.

Santiago Vega, executive director of the Carrillo Chamber of Commerce, analyzes the transformation of Guanacaste from the point of view of the absence of a government development plan.

The Government of the Republic didn’t have a clear plan (or a) development vision and there was a lot of land, [but] the people who had large financial capital and highly consolidated research teams decided to create a parallel development agenda,” he remarked.

Vega noted that not all of these real estate developments directly displaced families who lived there before. However, he says, a “rebound effect” did occur that made the inequality more evident. Around these developments, more popular neighborhoods began to be created for the people who historically lived in the area.

The director of the Carrillo Chamber of Commerce also pointed out that the State never provided training or support to people who had large tracts of land, nor did it contemplate a specific development vision for the province.

“In the 1970s, people arrived in Tamarindo and the surrounding areas and began to see the tourism potential. A sort of parallel development model began to be created that the central State’s vision didn’t take into account (…) They are two development models that aren’t coexisting; there’s no communication between them,” explained Vega.

He also pointed to a lack of auditing by the authorities. “In Guanacaste, they’ve denied that I can pay with colones; they’ve told me that you can only pay in dollars or with credit card,” he complained.

“This systematic neglect from the government and public institutions creates a parallel vision of development in which a merchant grants himself the power to deny customers payment in colones, which is the country’s official currency. Not to mention totally abusive prices for the Costa Rican population,” Vega cited as examples.

The mayor of Carrillo, Carlos Cantillo Álvarez, who has held the position for two decades, acknowledged that the canton’s urban growth, specifically in places like El Coco, has been “without planning at the inter-institutional level.”

Cantillo indicated that the municipality is currently preparing the regulatory plan for the urban area, since one only exists for the ZMT. He added that the process could take several years because different institutions must reach an agreement.

But, do you stop development for four, five or six years and work on planning? And with people waiting for jobs. So you have to strike a balance. I know that it’s complicated and at the national level, it’s complicated,” he justified.

Cantillo admitted that in some cases, construction permits are granted for houses or apartments but these end up being “small camouflaged hotels.” He said that when the municipality has detected advertising about lodging in these houses, the permits department has acted to regulate it.

He also insisted that the country has opted for tourism as a source of jobs and that, therefore, development can’t be stopped.

At the same time, the mayor criticized the lack of vision of residents. “We want to have the resources easily. And how is that? Selling our properties,” he said. According to him, there are families who sell properties near the beach, live off the interest but don’t reinvest in business ventures but instead let others generate the development. “There’s no vision or training to have challenges and be able to take advantage of this land that is very valuable.”

The mayor also pointed at AyA for the problems of access to water: “We have an AyA asleep that’s waiting for private companies to do everything for it. It’s not that there isn’t water. What there isn’t is infrastructure, and to have it, only private companies can provide it, because AyA doesn’t worry about it,” Cantillo said.

From ICT, both the Minister of Tourism, William Rodríguez, and the Director of Tourism Planning and Development, Rodolfo Lizano, ruled out there being any program to promote real estate development linked to tourism activity. “We don’t promote the construction of houses or apartments that later come to be used by tourists. Categorically not,” Rodríguez stated.

The minister added that ICT has no control over this type of development. “It’s a matter that depends entirely on the municipalities, in terms of giving construction permits,” he commented.

Both officials indicated that the investments promoted from that portfolio are businesses such as hotels, shops, restaurants or others directly related to tourism but that at the same time generate other associated jobs.

The minister pointed out that, however, in Guanacaste there is a great need to train “a mass of people who are needed to take care of tourism in an appropriate way,” since, in his opinion, the training efforts that have been done haven’t been able to satisfy the workforce demand. In this, he also attributed a part of the responsibility to the population.

“In all this, there’s always a lot of ground to cover, and in Guanacaste, specifically, there have been some demonstrations that tourism has not represented the benefit that was hoped for at some point, but I believe that this benefit isn’t something that depends only on one side; it depends on two sides. This is like having something put in front of you that you like to eat a lot, you take advantage of it or you don’t take advantage of it,” he said.

Rodríguez also said that the government doesn’t intend a “massification of tourism that comes to damage our most important attractions.”

For his part, Lizano stressed that, through the Social Progress Index (Spanish acronym: IPS), ICT monitors whether tourism generates well-being in the population and makes public policy decisions. He highlighted that several centers have better IPS than the cantons to which they belong.

We do a kind of strategic planning to see what the bottlenecks and problems are, and put an action plan in place for each of the 32 tourism centers. We’re making progress. We already have 16 and we have another six scheduled for this year. It will be El Coco’s turn,” the director of tourism planning and development indicated.

Meanwhile, the executive director of the Carrillo Chamber of Commerce pointed out that the central government’s lack of prioritization towards the area is noticeable when, for example, support is requested for training people, but the courses offered by the National Learning Institute (Spanish acronym: INA) are during business hours. “Then people can’t stop working, because they have to work, but they can’t get an education either.”

That chamber promotes a vision of “solidarity and responsible business,” Vega said. The majority of that chamber’s board of directors are foreigners. According to Vega, these people come from cities with a high population density where problems such as organized crime and drug trafficking arose, which is why they are concerned that the same thing could happen in Guanacaste.

The chamber is promoting public-private alliances and preparing projects related to creating a training school, the presence of traffic police and placement of security cameras, among other things.

Credits

Journalist: Hulda Miranda

Photography: César Arroyo Castro

Editing: María Fernanda Cruz and Noelia Esquivel Solano

Design: Roberto Cruz

Audience coordinator: Rubén F. Román

Translator: Arianna Hernández

Comments