Panama Beach residents are still waiting for the promised “tourist town”

From a distance, it gives the impression of being an oil painting of a typical scene from a coastal town: A man– perhaps a fisherman– with a straw hat and a beard that took days to grow, motionless, contemplating the ocean. After we approach the beach and begin to listen to him, Gadi Amit rather shows himself to be a wise man, a renegade investor and a stubborn environmentalist.

His beard is white, very white, spotless. His eyes are tiny and glassy. His sarcasm, acid.

He’s waiting for us on Panama Beach, with the wind in his face and his hat tied on well, ready to become something like our tour guide, but after a few hours and several miles worth of dust stuck to the body, the experience couldn’t be more antagonistic to that of a pleasant walk: “They displaced residents from here… They polluted here… In the bay, the corals threw a fit because of the oil from the yachts… Over there, they closed public access to a beach… Here, they stole the community’s water…” This is more or less how you could summarize the tour that would scare away any visitor who had been attracted by the Internet marketing that offers stays in the most luxurious “resorts” or advertises ocean-view houses for sale in exclusive communities, with prices in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

He likes to call himself a “citizen of the world.” With a Russian father and a Polish mother, Amit was born in Argentina, lived in Israel, where he obtained citizenship, and later moved to Costa Rica.

He’s been and done everything: chicken breeder and farmer in Israel; sales manager for Central America for a multinational company in Costa Rica. “At some point, I said: ‘I’m tired of living in San José. I’m going to Guanacaste. I closed up shop there and came to set up a business.”

As part of the great paradox of his life, his first business venture was within the Papagayo Gulf Tourism project. Six hectares (about 15 acres), 400 meters (1,300 feet) beachfront. About 600 people camped there one Easter Week, he recalls.

“But you can’t work with the ICT (Costa Rican Tourism Institute), because the ICT wasn’t interested in that. And then, since I was the only one there, I was the only one who could screw up, and the director of the Papagayo Project would come, [say] do this, do that. I put up with what I put up with and after a while, I said ‘no.’ And then I sold it and made my life, and my life was first to settle accounts with the Papagayo project and I filed all the complaints that ever were or ever will be in all of this.”

Around 1992, the Ombudsman opened an office in Liberia and Amit began to work giving training to communities in coordination with that entity. As a result of those meetings, a group of people was formed that ended up becoming the Guanacaste Confraternity, what used to be the name of a political party that existed almost a century ago that they have nothing to do with.

Now, the Guanacaste Confraternity’s name is associated more with constitutional appeals, investigations and the complaints “that ever were or ever will be” to protect the environment. Amit is one of the most well-known faces of that organization.

He chose Panama Beach (in Sardinal of Carrillo) to start our tour and it’s obvious that it wasn’t by chance. In front of us, peaceful and majestic, lies Culebra Bay and, from here, the panoramic view allows you to see the entire Papagayo Gulf Tourist Pole (Spanish acronym: PTGP), an area between the districts of Nacascolo in the canton of Liberia (in the northern part of the bay) and Sardinal de Carrillo (to the south). It spans from Cabuyal Beach to Hermosa Beach, including where we are.

The PTGP is a group of public lands that were granted in concession in order to bring investment and development to Guanacaste. The first steps of the project were taken almost half a century ago with the creation of at least three laws and, years later, a master plan was made.

A master plan that is useless and that they change every day to the liking and pleasure of the best investor that appears or of any interest that appears,” Amit reproaches.

According to him, Panama Beach was the area dedicated to tourism “on foot,” an area for camping, “but they erased it,” he says.

“Camping isn’t business, the townspeople aren’t business, backpacking isn’t business. They erased it,” he emphasizes with his obvious sarcasm.

Papagayo consists of 1,658 hectares (4,097 acres), of which 198 (489 acres) are protected areas and 1,460 (3,608 acres) are for touristic development. More than 30 concessions have been granted there, although some investors never built what they planned to, mainly because they didn’t have water availability.

Since the beginning of the project, Ecodesarrollo Papagayo S.A. obtained a concession for a large share of it (41% of the total area) and built an important tourist development in the northern part of the Pole, in the canton of Liberia, where the famous five-star Four Seasons hotel is located.

For several years, that company belonged mainly to the Schwan Foundation and a smaller percentage to the Costa Rican corporation Florida Ice & Farm (Spanish acronym: FIFCO). After a series of sales, its majority owner is now the American firm Gencom, and the Schwan Foundation remains a minority partner.

We travel by car through nearby streets. “Here, here. This is the entrance,” Amit points out, about five minutes later, when we can no longer see the ocean. He hopes that we will verify a promise broken by the promoters of the Papagayo Pole: the creation of a “tourist town” at Panama Beach.

“Here we’re now entering the town of Panama Beach. We have the soccer field, the church, the school, the pulpería (convenience store), the well that the ASADA (rural water board) had and that made a fuss,” he describes.

It takes a few minutes to piece it together and convince ourselves that this is really the point we were looking for. There are very few people on the street, the town doesn’t have a beach and is definitely not touristy. You can almost count the houses on your fingers.

“Let’s go to the pulpería,” insists Amit, who knows the neighborhood like the back of his hand.

The convenience store is called Greisy and is run by its owner: Grace Chavarría Soto, a dark-skinned 60-year-old woman with a slow and deliberate pace. Her parents came to this area decades ago and bought a property here, right where the convenience store is.

Grace’s family and other locals also had properties in the beach area, the one we left about five minutes ago. They used to do business there, but with the arrival of the Papagayo project, the ICT expropriated that land, says Grace.

“That was what brought us a lot of problems here, especially those of us who lived in the beach area. They expropriated our land, they promised a relocation that they never fulfilled, and they paid my parents a fairly low sum, whatever they felt like,” she says. The ICT had said that they compensated the people what was appropriate for these expropriations.

Grace was a teenager when all of this was happening. Now she looks back and concludes that “there was a lot of deceit on their part,” that is to say, by the people who promised them a relocation and new job opportunities.

The Voice of Guanacaste had already reported that the “tourist town” project at Panama beach had been considered since the first law creating the Pole. Ecodesarrollo Papagayo (which built the Peninsula Papagayo project) took on the commitment to draw up some plans.

Manuel Ardón, senior vice president and director of operations at Ecodesarrollo Papagayo, affirmed that this commitment was fulfilled in 1999.

It’s very true that this community has to have expectations because there is the idea of a tourist town at Panama Beach in the master plan. We, as Ecodesarrollo Papagayo Limited, had a specific commitment to plan, design and deliver some plans. That was the extent of our obligation. Beyond that, it’s now up to the ICT, the government, the Pole office, to carry out the execution of the material works,” he affirmed.

The Papagayo Gulf Tourist Pole functions as a decentralized body within the ICT, which is why it has its own executive management, headed by Henry Wong.

Wong indicated that the concession holder did indeed deliver some construction plans and that the project to create a tourist town is still current. “The commitment is to work with the corresponding institutions and players to move forward in this project,” he replied.

The Minister of Tourism, William Rodríguez, described Panama Beach as one of his main concerns and stated that he has had conversations with the community to find out their needs. He specified that a wharf is being built and that other complaints have been addressed, such as building a police station and having training in different areas. “At least since I took office, we’ve paid a lot of attention to the people of Panama,” said the minister.

Meanwhile, Grace claims that she has seen how “hotels on the beach have wanted to remove small vendors.”

Let’s say, the lady who comes to sell fast food, or the one who comes to sell hats, bandanas or any kind of ceviche,” says Grace.

As she tells it, the townspeople devote themselves to offering tours on jet skis, 4-wheelers or on horseback for tourists. There are also some who make a living from fishing.

The convenience store has allowed her to raise her three children. Of course, when the two oldest went to university, they had to take out student loans, and now that the youngest finished high school, the same thing will probably happen.

That’s why Grace thinks that it would be ideal for tourism to expand to this town, just as it has at Playa Hermosa, Playas del Coco or Tamarindo. She lets go of that idea and immediately questions herself: “Although many other things that are harmful to youth come with that, because if there is progress, vices come,” she says.

Her concern might be justified by the experience of other communities where development has exploded. Although the statistics for coastal districts don’t show a rise in crime in recent years, violence throughout the province has increased when measured by its main indicator, which is homicides. These went from 24 in 2015 to 61 in 2022 and the most affected canton is Santa Cruz.

Although there’s no single explanation for this increase in violence, authorities have mentioned the presence of more drug trafficking organizations and drug dealing on the beaches, which urban growth could have contributed to.

For Grace, not even the lack of job opportunities there could make her leave her community.

The other day there was a Canadian telling me to sell him and I didn’t want to. First of all, he even has to pay me for the nostalgia, you know, for so many years of living here… It even makes me feel a lump in my throat,” she says.

While at Panama Beach, they’re still waiting for a promised tourist town, at the other end of the Golfo Papagayo Tourist Pole (PTGP), real estate and tourism development is evident.

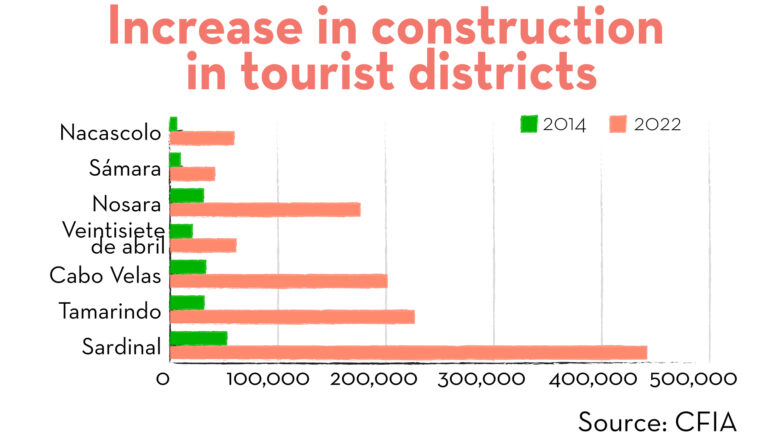

Data from the Federated College of Engineers and Architects (Spanish acronym: CFIA) show that the district of Nacascolo, in Liberia, (the northern part of the PTGP) had the highest growth in intention to build, in terms of percentage, in the last eight years. In 2014, the intention to build was less than 6,000 square meters (about 64,500 square feet), while last year, it was 59,035 square meters (635,447 square feet).

Social Conflicts

The connection between people from coastal communities with tourism megaprojects has shown manifestations of a phenomenon called overtourism, which researcher Ernest Castañeda, from Alba Sud Spain, explains as an uneasiness and rejection of tourism by the inhabitants because they feel that there is saturation.

Castañeda referred to this concept in an article published in 2019 entitled “Conflicts over water in Guanacaste, Costa Rica.” In it, he mentions an episode that brings us back to Gadi Amit , which he tells us about in person:

“What you have to understand in this Papagayo development, and Panama Beach in particular, is the issue of water. Having planned the development for a limited number of people and having increased that number, water usage was totally increased. The Panama Beach aquifer was overexploited and depleted to the maximum. It became salinized,” he recalls.

In 2016, the families in Hermosa and Panama were left without water when what researchers had warned about 15 years in advance came true. Gadi tells us about it now. In times of drought, freshwater diminished and the aquifer became salinized, unusable for human consumption.

It was something that the Guanacaste Confraternity already fully suspected could happen. That’s why, since 2008, they had asked the Constitutional Court to force the Municipality of Carrillo, the Institute of Aqueducts and Sewers (AyA) and the ICT to take measures to take care of the aquifers in the face of the impact of real estate and tourism development. Since that time, the Court had agreed with the Confraternity.

They didn’t give a crap. The water from Playa Hermosa ran out, it began to be fed from Playa Panama and Playa Panama collapsed,” Amit expresses bluntly.

The authorities had to take some emergency measures such as water distribution with tanker trucks and expanding the aqueduct for Panama Beach and Hermosa Beach. In 2019, the Las Trancas-Papagayo aqueduct was inaugurated. The government promised that it would not only supply these communities with water again but also to cover the Tourist Pole, where some investors claimed that they couldn’t carry out their construction projects precisely due to the lack of water resources.

But that passage narrated by Gadi Amit is just one of the many that exemplify the environmental conflict deepened by tourism and real estate development.

Briefly, it could be mentioned that more than a decade ago, residents of Playas del Coco expressed concern that water would be taken from that community to Ocotal Beach to supply a project of more than 300 luxury residences called Azul Paraíso, where properties had been sold even without having drinkable water.

Making illegal wells in condominiums and shortages in other areas of Sardinal could also be mentioned, as well as overexploitation of water flow in Tamarindo and conflicts over water administration in Potrero Beach (the latter two communities are in the canton of Santa Cruz).

To date, the need for drinking water continues to be such an urgent problem for the province of Guanacaste that the previous government administration put into motion the PAACUME project, a component of the Integral Water Supply Program for Guanacaste (Spanish acronym: PIAAG), which is intended to improve water distribution to the cantons of Carrillo, Santa Cruz and Nicoya.

A more recent episode of conflicts over water management and clashes with developers occurred in the small town of Marbella, in Santa Cruz in Guanacaste, a hideaway with paradisiacal beaches. Around 200 families live there and the community has begun to see a thriving business sprout up that remains in the hands of a couple of developers.

In 2017, The Voice of Guanacaste made it known that American investor Jeffrey James Allen served as president of the Posada del Sol ASADA and, at the same time, as one of the real estate project developers in Marbella. To date, Allen faces a criminal investigation for irregularities such as granting letters of water availability without studies. This news medium tried to talk to him but his office staff indicated that he wasn’t available to answer questions.

That was one of the incidents that researcher José Arturo Silva compiled in his most recent publication, Tourism Reactivation and Socioecological Conflicts in Guanacaste, in which he analyzes cases from the communities of Marbella, San Juanillo, Ostional and Nosara.

To all this, add the environmental pollution documented over the years. In 2008, when the Guanacaste Confraternity was already concerned about the consequences of tourism development in the Pole, the Ministry of Health closed the Allegro Papagayo hotel, located on Manzanillo beach, due to contamination with wastewater.

In Tamarindo, since 2007, evidence of poor wastewater management was recorded. However, the sanitary sewer system won’t arrive until 2026. The same has happened in Playas del Coco due to the absence of a sanitary sewer system.

And in Culebra Bay, where we met Gadi, the live coral coverage went from 80% in 1991 to 5% in 2021, according to data compiled by Ojo al Clima.

Manuel Ardón, senior vice president and director of operations of Ecodesarrollo Papagayo, told The Voice of Guanacaste that although it is true that the country’s tourism development has brought good things at the same time as impacts, it’s important to do a “specific analysis of the projects” and not general assessments. “Because not all of us do things in the same way and some of us end up being criticized due to generalities,” he said.

Ardón said that the Papagayo Peninsula project has had a “triple utility” strategy since its inception, “where the social part, the environmental part and the economic part are clearly established.” He assured that sustainability goals are set, in which the opinions of people from surrounding areas are considered, and that they currently have an association called Creciendo Juntos (Growing Together), through which they have a “very close relationship with 19 communities around the Papagayo Peninsula”.

Among the benefits for the communities, Ardón mentioned the creation of almost 1,700 jobs, of which 90% are occupied by people from nearby communities, according to him. He also highlighted the promotion of education by means of technological support and programs for teaching English, among other things.

According to him, the project is not “taking water from anyone” either because before its construction, the amount of water resources required, the sources and the way to manage it were determined. He affirmed that this hasn’t changed and that the water is recycled for irrigation.

Ecodesarrollo Papagayo’s director of operations maintained that the company has a commitment to the environment and that it has even financed the studies with which it has been possible to determine the decrease in corals.

You can’t reach the conclusion that what happened in Culebra Bay is exclusively due to tourism development. There are a number of factors. In the world, there has been a general bleaching of corals due to climate change. Now, all development has an environmental impact. Whoever says that it doesn’t is lying, but with sustainable development, we make a lot of efforts to measure these impacts and find ways to minimize or nullify them,” explained Ardón.

As an example, he indicated that for two years, they’ve been part of a program to replant corals in the bay.

The Beaches Are Public

Near Hermosa Beach, we climb deserted hills from which one can have the best and most envied view of the Papagayo Gulf. On the other side, the red tile roofs of luxury condominiums can be seen. Sociologist José Arturo Silva, from the Alba Sud organization, describes many of these homes as “second homes,” in other words, homes for people with high incomes who use them for vacations or rent them out.

Silva thinks that the phenomenon of gentrification in the coastal area of Guanacaste is, to a large degree, related to this type of real estate development. According to his analysis, this happens when investors arrive and change a region’s land use, build luxury buildings and push the area’s historical residents to concentrate in poorer areas, to make space for wealthy new neighbors.

Gadi reminds us that some of these luxury buildings were built years ago, when they didn’t even have drinking water available. Then he explains that many of these homes are part of a “tourism paradigm shift.”

“Before, tourism was beachfront, the hotel, the guest house, the place in front of the beach. Now foreign tourists come, gringos basically, and they want to build second homes in a model called Ocean view. They want to have an ocean view from the house. They aren’t interested in being near the beach. When they want to, they go down to the beach, but they want a view of the ocean,” he says, describing from his observation what researchers have also documented.

The Internet abounds with real estate advertising with key phrases like ocean view and gated community. The new model of tourism development is evident in construction statistics, but also in the red tile roofs and high walls that stand out in high places within this coastal area. Wherever there is a hill, perfect for a new and exclusive residential area.

Researcher Silva explains that social and ecological conflicts have been part of the impact that the tourism development model has had on the Guanacaste coast. It’s also an indicator of the phenomenon of gentrification, he points out.

Some time ago, when tourism development in this province was more focused on large hotels near the ocean, some of the most notorious conflicts were related to closing access to beaches, which was interpreted as underhanded attempts at privatization.

One of the most publicized cases was that of the Hotel Riu, on Matapalo Beach, in 2011, when the community denounced an attempt to close a public access to the beach. The owner of that hotel, Luis Riu Guell, is on the verge of going to trial for environmental damages due to complaints from the Guanacaste Confraternity.

In Brasilito of Santa Cruz, residents held a demonstration in 2018 because they claimed that their neighbor, the Reserva Conchal, closed access to take over the beach. The company, for its part, announced that it sued the state for the environmental damage caused by vehicles going on the beach, that this was the reason for having placed some metal tubes and that it didn’t intend to prevent pedestrians from passing through.

However, within the manifestations of gentrification, the closure of ways to get to beaches are one of the easiest conflicts to resolve, because investors are usually forced to allow passage, Silva affirms. Nonetheless, sometimes certain traffic restrictions will be maintained under arguments such as preventing environmental damage, or sometimes the enabled roads aren’t exactly the most accessible.

Due to situations of this type that have occurred over the years, the “paso prohibido” (no entry) signs or fences placed at points that were known as accesses to beaches continue to cause suspicion.

Here, where we parked, is Punta Cacique, in Carrillo, a street about 3 kilometers (about 2 miles) long that leads to beaches like Penca and Calzón de Pobre.

“The entrance to this street was closed with a gate from a building. Investigating, we found out that this was a public street, we denounced it and we succeeded in demolishing that entire gate and authorizing it as a public street. That was about 10 years ago. People thought that this was private property, so we began to bring students, tourists, we started making the custom and everyone began to enter here,” Gadi tells us with a smile that’s impossible to hide.

At the very tip of Punta Cacique, on Penca Beach, the Waldorf Astoria luxury hotel from the Hilton portfolio is currently being built, which is being developed by the Costa Rican firm Garnier & Garnier, a real estate company with significant investments in Guanacaste.

The hotel will have 190 rooms and 25 residences, according to information released by the company.

Construction machinery is the reason why going through there has recently been regulated. Everyone who arrives hears that explanation from Fidel Espinoza, a retired former police chief of the Public Force who, in his working life, was dedicated to guarding the Maritime Land Zone area and now looks after cars to earn some extra money. “When the hotel is finished, there will be entry in the same way,” repeats the man who wears a cap with yellow letters that say “Security.”

He mentioned it a few minutes ago to some Costa Rican tourists who came from Alajuela and who were concerned about the eventual closure of that access to the beach, which could only be reached by water at this time.

Fidel has no connection with the construction work or with the hotel company, but he offers information to visitors as he did in his time as an officer in the Maritime Land Zone. He believes in the need for tourism development to create new employment options, but like almost any Guanacastecan, he is concerned about two things: the impact on nature and that “in a few years, there won’t be any water.”

After talking with Fidel, we continued on our way to Playas del Coco. Despite the sweltering heat and hours of conversation, Gadi Admit looks relaxed. He seems to be used to giving guided “overtourism” tours in Guanacaste. He doesn’t get tired, not even when the raging sun beats down on his head. He’s protected by his straw hat.

Credits

Journalist: Hulda Miranda

Photography: César Arroyo Castro

Editing: María Fernanda Cruz and Noelia Esquivel Solano

Design: Roberto Cruz

Audience coordinator: Rubén F. Román

Translator: Arianna Hernández

Comments