Since mid-November, the menus of several restaurants in San Jose have included a handful of drinks and dishes featuring the same seed: pujagua corn.

Tacos, tamales and even drinks are some of the ways that chefs have prepared the type of corn, so common in towns like Nicoya but so little explored outside of Guanacaste.

So how did pujagua make its way to San Jose restaurants?

To answer this question, we need to make several stops along the way on a journey of almost three years, during which Guanacaste farmers have learned more about their soil, improved their crop harvests, collected recipes and, finally, went out in search of clients.

A Route That Germinates

All journeys begin with a first step, and all of our meals begin with someone who sows a seed. Or even before that, with someone who prepares the soil for that seed.

Earth University initiated a project in 2018 to encourage farmers in the province to prepare their land and market their seeds.

The chef and owner of CanelAzul, Daisy Barrantes, prepared two quick and simple corn recipes for us

This was done through Earth Futures, a rural impact center that brings the knowledge of the university to the communities. The objective of this project financed by the Crusa Foundation is to strengthen the productivity of cultivators and, at the same time, give them tools to improve access to markets where they can sell their crops.

“The question was how could we support corn farmers from the university to produce more efficiently, but also with less environmental impact,” explained Karina Poveda, the manager of developing solutions from the School of Agriculture of the Humid Tropical Region.

To achieve this, they carried out a series of physical and chemical analyses of the soil so that 42 producers learned about the condition of their farms and made decisions based on that information.

Rio Montaña is one of the communities that form part of the project with the aim of strengthening production and market access for small corn farmers in Guanacaste.Photo: Karina Poveda

One participant is Gualberto Obregon, from Polvazales de Mansion, in Nicoya. There he sows corn, rice, beans, yucca (cassava) and the occasional vegetable that he now treats with fertilizers that he was taught to make at home.

“Making [your own] microorganisms, organic fertilizers, liquid fertilizers is also going to reduce a lot of cost in agriculture because we depended on the synthetic fertilizers that they sell, which makes agriculture more expensive and hurts people as well,” said Obregon.

In addition to Polvazales, Earth University also selected Nicoyan communities such as Corralillo, Rio Montaña and San Lazaro because they detected that they were places with producers who were organized or who had received previous training from other institutions on related subjects.

Guanacaste, Stronghold of Local Seeds

Corn production in Costa Rica has been declining for more than 10 years, explained Poveda. Among the causes, she listed the complexity of producing due to climatic factors but also due to the market.

In Costa Rica, corn is imported from countries like Nicaragua, where it is produced at a lower cost than it costs to produce here. So there is an unfair competitiveness for our country’s farmers,” she added.

Even with the complicated scenario, the Chorotega Region is one of the three most productive corn areas in Costa Rica. The other two are Brunca and Huetar Norte, according to the 2012-2019 Basic Grains Situation Report: beans – corn.

What makes the Chorotega Region distinct is that it still preserves local seeds.

Poveda added that these are seeds that have more viability to reproduce, which is different from areas that have hybrid varieties, in other words, varieties that are the product of a natural or artificial cross between different varieties of the plant and, as a result, the seed that it produces is not fertile enough to continue reproducing.

“In terms of genetic variability, it is super important [to have native seeds], especially considering that with climate change, we are facing conditions [in which] we don’t necessarily know how they will behave,” Poveda pointed out.

“My grandfather, my father, my uncles, my great-grandfather, they all worked here. They were pioneers of this seed, of this knowledge that they have. Seeing myself on that marketing front was a very valuable experience for me ”. – Gualberto Obregon, farmer.Photo: Angélica Sánchez

Gualberto Obregon, the producer from Polvazales, said that the seed he inherited from his grandparents now meets conditions that they have been perfecting for decades.

Today we have seeds that we have believed have adapted better to our soils, to our climate and that give us better yield, better color or better flavor,” the farmer emphasized.

Despite having quality seeds in their hands, they still had two more obstacles on the route to San Jose restaurants: how to promote and sell them?

Corn to Table with No Middleman

“In many parts of Costa Rica, this [gastronomic] culture related to corn was lost. So when we wanted to look for ways to market the corn, people didn’t know what to use it for,” lamented Poveda.

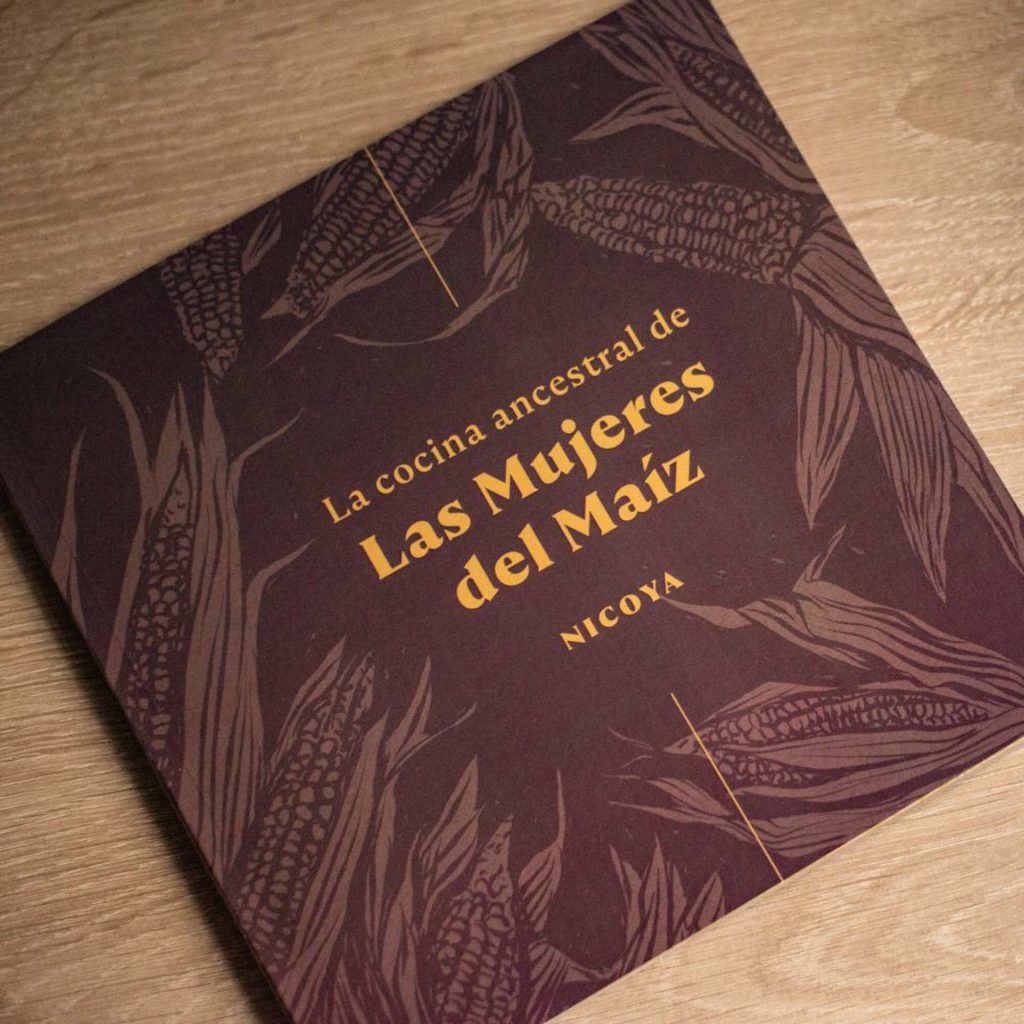

That’s how they came up with the idea for a cookbook that would let people know about the nutritional and cultural value of pujagua, as well as the faces and communities behind these dishes.

Hand in hand with the groups Coovida and Las Mujeres del Maíz (The Corn Women), which seek to preserve Guanacaste’s ancestral food, they organized a recipe book with the favorite dishes of the women participating, who are farmers and bearers of the culinary tradition at the same time.

With the book under their arms, Poveda and Obregon headed towards the last stop on this almost three-year journey: finding restaurants in San Jose to position their products.

It wasn’t just Earth University seeking alliances with restaurants, but someone that represented hundreds of corn farmers that exist here in Guanacaste,” said Poveda.

Thanks to an alliance with the National Chef Association of Costa Rica (ANCH for the Spanish acronym), they contacted chefs from different restaurants and hotels. Along with Obregon, they talked about the value of corn, how it is produced, who is behind this production and why it’s important not to lose the native seed.

They launched a campaign called The Pujagua Route and asked the chefs of five restaurants to develop a dish that would include pujagua corn in their recipe, something related to the cookbook but also open to their creativity. To prepare them, they had to commit to buying at least one quintal (46 kilograms, which is about 100 pounds) of corn at a fair price.

The five chefs did their thing: they bought the corn and included recipes on their menus like purple corn ceviche, chicken empanadas and chicheme cocktails with white rum. They will keep the dishes on their menus during December, but the story may not end there.

The idea is that once the route is finished, the chefs and the farmers can stay in direct contact,” said Poveda.

Obregon explained that this is a new step for farmers since he said that they have always been inhibited and at the mercy of the prices imposed by intermediaries.

“A cloak was torn away, a curtain that had been there for many years. That fear of going to look for the buyer was broken,” Obregon emphasized. “We were able to go to the Greater Metropolitan Area and be face-to-face with the buyer, who likes the product.”

Do you want to satisfy a pujagua craving or try it for the first time?

Get the recipe book La Cocina Ancestral de Mujeres del Maíz (The Ancestral Cooking of the Corn Women) by writing to [email protected].

Remember to take advantage of the final days of this year to go and try these dishes that make up the Pujagua Route:

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Comments