On the morning of October 5, 2018, Marcela Reyes stretched her arm out while in bed and felt water, as if she were touching some lake or splashing at the seashore. It was not a dream. While she was sleeping, the Nosara River broke into her house.

Stories like this abound in Santa Marta, Central Nosara and the Hollywood neighborhood, which is where Reyes has lived for about 10 years. The river runs just 20 meters (65 feet) from her house’s door and is like another visitor during the winter, but it had never struck her as “so horrible, so scary” as in 2018.

From her house, it is easy to see the dike, which is almost destroyed in certain parts. At this time, it is “useless,” according to the National Underground Water and Irrigation Service (Senara), which is the same entity that built it.

In 2009, the Nosara Integral Development Association (ADIN), along with several other area residents, managed to get the Constitutional Court to order the National Emergency Commission (CNE) to dredge the Nosara River and build a dike. Senara and CNE started the work in 2013 and completed it in 2015. At that time, it invested ¢1.149 billion (about $2 million).

In 2020, Senara and the CNE planned to invest another ¢650 million ($1.2 million) to rebuild it. In total, ¢1.799 billion (about $3.2 million) will have been invested in the dike.

According to the president of the ADIN, Marco Ávila, the CNE explained to the Nosara Emergency Committee that the project will start until the summer of 2021, as the institution made budget errors that were resolved until April 2020, a month before winter starts.

With that plan, Ávila said, they will maintain a gabion wall and make the lining of the structure in the vicinity of the Nosara aerodrome, the Santa Marta community hall and National Route 160.

But how efficient is it to invest resources in this dam? A new hydrological study of the Nosara River by the National Meteorological Institute (IMN) contends that the dike is not effective and that the river, even in areas where the structure exists, can flood with much less rainfall than what was projected by Senara.

If one looks at the dike in terms of cost and benefit, it isn’t necessary to figure out the numbers. It is a fact that it did not work,” said the study researcher, Javier Saborio. “It flooded two years after it was installed. In other words, it was not an effective solution,” he added.

The IMN study emphasizes that floods are “inevitable.” The river starts at more than 900 meters above sea level and that height turns the current into a kind of natural canyon. Its connection with the Montaña river basin and other smaller basins also cause greater water flow in the lower areas like Nosara.

To this, it must be added that settlements are practically within the riverbed or along the shore. In other words, according to Saborio, the problem isn’t the river; it’s “bad planning.” “Then we fight against nature and believe me: fighting with nature is senseless.”

However, it is also a problem of calculations and magnitudes.

Saborio built scenarios that simulate the river basin’s response to future rains. For these scenarios, he classified events like hurricanes or tropical storms according to their magnitude.

Senara says that the dam can withstand a 25-year return period. Scientists call that number of years a “return period” and it is the measurement they use to calculate how big the “maximum event” of rain that a hydrological construction can withstand. For example, Tropical Storm Nate lashed the country in 2017, flooding Nosara, is equivalent to a 50-year return period.

However, IMN’s results show that the river can overflow with return periods of between five and 10 years.

“Even though there is a dike, the flooding is going to continue,” Saborio insists, explaining that it’s like covering up a balloon that has several holes.

Even if one is covered, the water is going to look for a place to escape.

The director of engineering and project development for Senara, Marvin Coto, defends the work and says that the floods “would have been much worse without the construction.” However, nobody and nothing can ensure that there won’t be more floods in the future.

“When you build works like that, you cannot guarantee that it will never flood again. It would be irresponsible. We cannot say that it is an infallible work,” Coto emphasized.

It’s Falling to Pieces

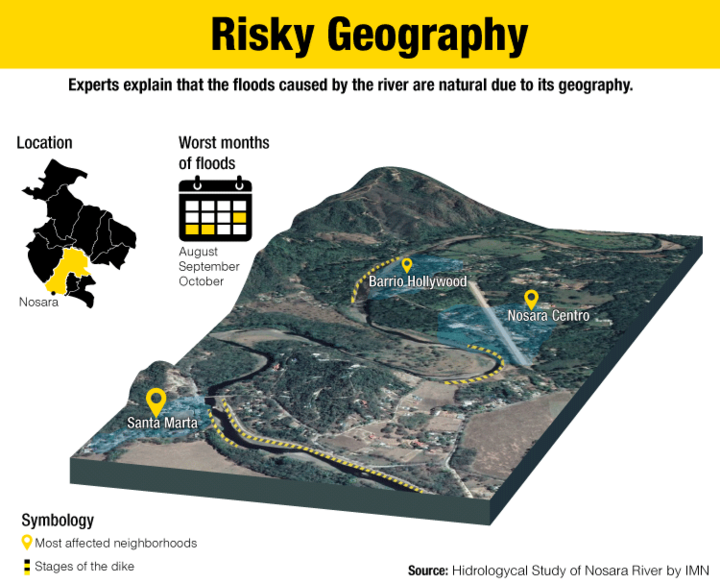

The dike is divided into three stages located between the Nosara airport area and the Santa Marta neighborhood. Altogether, it measures about 3,000 meters (almost 2 miles) long, along which there are now evident cracks and overgrown grass.

Coto, from Senara, blames the damage on lack of maintenance, which by law is the responsibility of the Municipality of Nicoya. “The dimensions of the dike are fine. [The extreme floods] happened due to lack of maintenance. For a while, there have been trees there and that has been cracking it,” he emphasized.

The head of the local government’s department of construction control, Josue Ruiz, says that in 2019 they did perform a “light maintenance” (preventing tree roots from growing in the river) and justifies that they did not do it sooner because it wasn’t until that year that Senara sent them the plans. In 2020 the dam has not received new maintenance.

Coto’s justification for the dike’s future reconstruction is that the rains did not “surpass” it. In other words, they did not destroy it completely. He also explained that they cannot widen it more because there is not enough money. “You can build much bigger if you want and upgrade to a return period of 25 to 100 years, but we’re talking about works with very high costs.”

Things Don’t Get Better

According to the Nosara Development Association (ADIN), the areas most affected by flooding are the Hollywood neighborhood, Santa Marta and central Nosara.

Aryeri Cabrera moved into a place a few meters from the river, in the Santa Marta neighborhood, two days before the 2018 storm. She related that she and her family put up sandbags and old sheets of metal roofing to try to keep the water out of the house, but that didn’t help at all.

She says she is also “resigned” to having her house become “part of the river” in certain months of the year. To prevent damage, she has built wooden drawers to put the appliances up on. She also plants espavel (wild cashew) and sota caballo (Zygia longifolia) trees along the river banks because someone told her that they help.

She says she would leave there, but she doesn’t have other housing options.

“If they give me a plan to get out of here, I would have my little bags packed already. I don’t see things getting better.”

These are exactly what the IMN report recommends as short-term measures: reforesting native species on the river banks, using sandbags around houses and elevating valuables in danger zones. However, Saborio emphasized that the definitive solution is to relocate families to higher areas.

Coto, from Senara, agrees that the dike is only part of the solution. “Maximum events much worse than Nate could happen and that now is out of our hands. The dike goes hand in hand with other solutions, but it is neither the only nor the definitive one,” he explained.

The Municipality of Nicoya still doesn’t have any proposals to relocate people. In 2018, ADIN proposed a project called Casas Nosara Unida (United Nosara Houses) to move the 40 families from the Hollywood neighborhood to land in Santa Teresa of Nosara, but the municipality denied the permits.

The president of ADIN, Marco Avila, said the project is still on the table, although the organization needs to raise more funds to adapt the land.

“The project is noble and we fully support it in the municipality. However, they need to make sure that it complies with details such as the elevation level of the land and others. No exceptions,” commented Ruiz from the municipality’s engineering department.

Comments