Sharon was so little that she doesn’t remember how old she was when she crossed the border. She doesn’t remember the journey either or anything else that she experienced and left behind before then, but she does know the reason why. She and her grandparents left Nicaragua because there was need in their home – there was hunger – and immigrating seemed like a path that would give hope to her family.

Although she hadn’t been taught to dream but rather to make do, she arrived in Costa Rica as a girl who wanted many things, but as time went by, she didn’t see the light at the end of the tunnel. Immigrating had not changed her life, and vulnerability, poverty and hunger were still there, tangible.

When she was only in fifth grade, she lost patience, “took to the streets” and met her current partner. She was 12 years old and she went to live with him. Since then, she felt ready to be a mother.

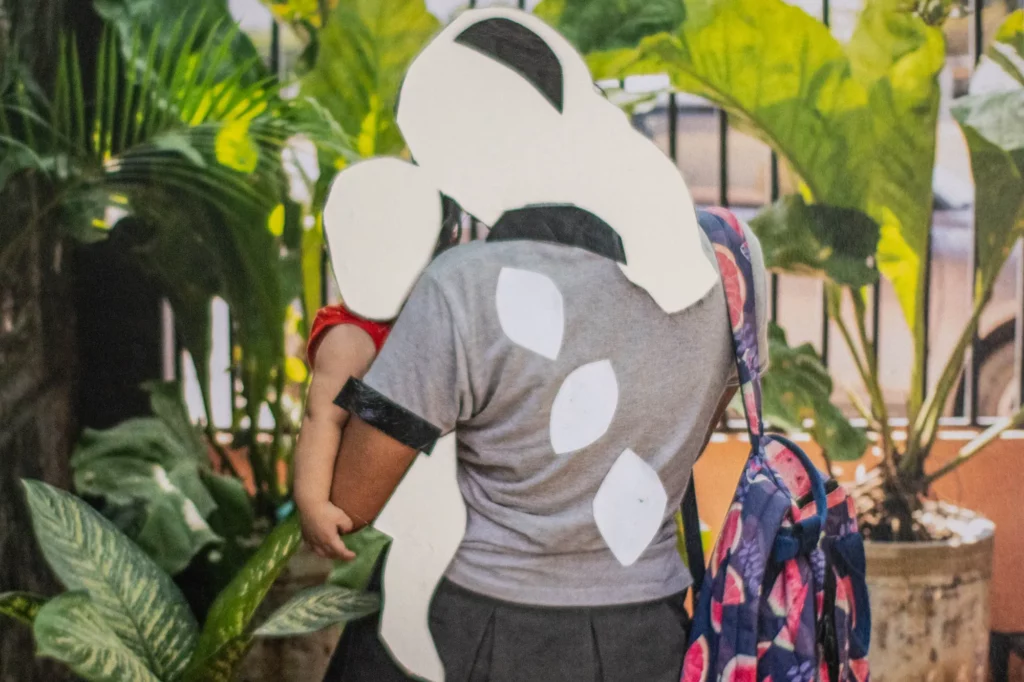

Sharon is now 26 years old and has spent more than half of her life in Guanacaste. She has long legs, prominent cheekbones and dark skin. She speaks with a soft voice and short sentences, and she smiles every time she finishes a sentence. She likes Mexican soap operas and romantic movies, but possibly what she likes most in life is being a mother.

Sharon has six children, ranging in age from one month to nine years old.

The first time she got pregnant, she was 17 years old. She was afraid of not knowing how to push, of not understanding that animalistic need, that unbridled rhythm of a body that splits open to give birth. She was afraid of doing it wrong, of inhaling when she should exhale and that – while panting– the girl would suffocate.

Doctors and nurses held her hand and told her to calm down, that she could do it, that everything was going to be alright, that she should push one more time. And another. And another. And Sharon listened. From some corner of her soul, she drew the strength to use all of her energy and break out in silent screams and tearless sobbing until she heard, for the first time, the lively cry of her daughter. Her legs were shaking so much that she thought she had turned into a bug, a cricket with skinny, fragile legs that couldn’t stop moving.

She knew that she was still herself when they placed her daughter on her chest. She saw her face and felt her warmth, and she felt like the happiest person in the world.

Before giving birth, Sharon searched the Internet for unusual names. She searched for them by letter and by meaning until she decided that her daughter would have a name of Arabic origin that she says sounds beautiful and uncommon. We’ll say that the girl’s name is Kenza.

In 2017, when Kenza arrived, she was one of 1,497 babies born in Costa Rica to Nicaraguan teenage mothers between 15 and 19 years old, according to statistics collected by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

Although the numbers of births by teenage mothers have decreased considerably in Costa Rica in the last 20 years, young pregnancies continue to be a latent public health problem. In 2022, 268 out of every 1,000 women (between 15 and 19 years old) became mothers. In almost one-fifth of those births, the pregnant teenagers were Nicaraguan, like Sharon.

***

With a hoarse and tired voice, Carmela invited everyone she saw on the streets of Managua to buy a scratch-off lottery card from her and try their luck. It was a hazardous job not only because of its nature, but also because it put her own luck to the test. She never knew if she’d have enough money to take home at the end of the day. She was 16 years old and she was already the mother of a baby a few months old.

When she gave birth for the first time, she didn’t believe it was real. She saw the baby with his skin so tender and his eyes so bright, so recently formed, that she thought he was a doll. That fantasy of plastic and playful motherhood was broken every day when she counted the coins she had earned selling scratch cards and she realized that it wasn’t enough for milk, diapers, food. That’s why, like thousands of other Nicaraguan women, she made the decision to immigrate to Costa Rica alone, without her child.

She wanted to make money to send to him and give him a better life. She settled in Playas del Coco, in the canton of Carrillo, and she invented her own businesses to try other types of luck. She became a seller of tortillas, nacatamales and souvenirs. During those comings and goings, she met her current partner and, at 17 years old, she became pregnant again. That time in a country that wasn’t hers.

The day she had her second child, Carmela was alone in the house. She grabbed hold of a wall and pushed. She squatted down and pushed. She forced her lungs to breathe downwards, as she had been taught during her first birth, so that the baby wouldn’t climb upwards but instead would seek its way out toward the light. “I brought him into the world by myself,” she says proudly.

And as time passed, pregnancies came, births took place. By the time she turned 23, Carmela was already the mother of five children. Of the four who were born in Costa Rica, three came into the world at home. She decided to do it this way because she was afraid of the hospital, afraid that because of her immigration status, they would take her children away from her or they would deport her to Nicaragua with her entire family. Her youngest daughter – who was born premature – was the only one she gave birth to at the Hospital in Liberia.

There is a repetitive cycle that makes it difficult for pregnant immigrant women to access health care. Along with minors, they are the only two populations for which the Social Security Fund makes exceptions to provide care without insurance and free of charge. But misinformation and fear intertwine and keep these two vulnerable populations away from health care. This happens every day, affirms gynecologist and obstetrician Daniela Ordóñez.

“The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that every pregnant woman go to at least eight prenatal care appointments. However, many come just to give birth or even have out-of-hospital births,” she said, referring to women who come in during an emergency, sometimes with newborn babies in their arms, like what happened to Carmela.

The doctor also clarifies that a teenage pregnancy is always classified as high risk because it occurs in a body that is still developing. Daniela works at the Los Chiles Hospital, near that hot and porous border line that divides Costa Rica from Nicaragua. She constantly sees cases of pregnancies in minors who have a vulnerable immigration status.

According to UNFPA, in 2022, of the 466 teenage girls who became mothers in Guanacaste, only six out of 10 went to the eight prenatal consultations recommended by WHO. However, 98% of the young women did give birth in a Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS) health center.

According to Daniela, the fact that girls and adolescents arrive at the CCSS’s clinics means that a social worker can then support them and give them information about their sexual and reproductive rights.

When Carmela was little, she never imagined being a mother, but she didn’t see any other way. She never had time to question it. She’s still selling colorful bracelets and necklaces with turtle charms to tourists on the beach. She works with her daughter, who is now a teenager, and tells her – or rather warns her – not to “throw her life away” with a premature relationship, not to “make a mess of it” with an unwanted pregnancy, to be careful, to “not be like her,” to look towards the horizon and discern that life puts different paths in your hands.

***

“In all of the cases, I’ve seen a lot of hopelessness, helplessness. The girls give a feeling as if they are no longer there, as if they hit a wall. They had a pregnancy and they no longer see any other possibilities than to dedicate their lives to taking care of that baby. They don’t see opportunities for anything else and it’s hard to motivate them. In addition, the families repeat it to them; they tell them that they asked for it, that they threw their lives away. There’s always talk of blame.”

The person who said that is Karla Marín, a psychologist. For five years, she has been working with Cepia, an organization that seeks to improve the quality of life of children, adolescents and families in vulnerable communities in Guanacaste. Karla is the coordinator of the youth group. During the last few years, she has seen several teenage mothers, all Nicaraguans, [participate in the group. Some don’t come looking for help for themselves directly, but rather for their children in one of the programs offered by the organization, such as daycare services or aid for minors with disabilities.

According to her, when they identify a case of teenage motherhood, they usually notice certain patterns that are repeated from one generation to the next. The teenage girls know that their mothers were mothers when they were very young, and the mothers know that their grandmothers were, too. From her experience, Karla says that breaking with this normalization and these cycles is an educational, economic and social challenge, comprehensive work that involves not only young people, but also families, communities and public institutions.

“We had the case of a girl who came in when she was 16 years old and already had a three-year-old daughter. Cepia already knew about the case because the girl became pregnant when she was at school. Her mother took care of the baby as if it were her own and this caused the teenager to not take responsibility of any kind for her daughter. The girl is no longer part of Cepia, but we found out a few months ago that she’s pregnant for the second time,” she said.

Karla says that she has been able to notice two extremes of family support. Sometimes it’s zero and talk of blame can become violent; other times, it’s excessive and gives rise to little awareness and responsibility regarding motherhood.

Another issue linked to teenage pregnancy that Karla considers essential is improper relationships. “Boys and girls come with a lot of doubts about sexuality. They know almost nothing because no one has ever explained to them about contraceptive methods, taking care of themselves, not even the subject of personal hygiene. And then there is the ‘sugar daddy’ tendency, which has to do with the coastal location we are in. The issue of dating men has become normalized. The girls say, ‘I’m going out with a man, he’s going to pay me and it’s not bad.’ So here they begin to be told that this is not good, that there’s a law that prohibits it and they begin to become aware.”

Karla added that there’s a fine line between improper relationships and sexual exploitation. In some cases in which Cepia has had to intervene, it’s the families themselves who encourage their daughters to have a relationship with an older man because that means valuable income for a fragile family economy.

The United Nations estimates that, worldwide, nearly 15 million girls under the age of 18 get married each year. That’s about 37,000 girls a day. Getting married young or living in a common-law marriage also deeply affects access to education and, therefore, the ability to get a decent job and have an independent life.

“Reporting situations such as sexual exploitation and improper relationships is not embraced by part of the population, especially people who come from Nicaragua, because in that country, there is no legislation that punishes improper relationships like what happens in Costa Rica,” said Evelyn Durán, UNFPA reproductive health analyst.

She also mentioned that it’s hard to know how many teenage pregnancies in Costa Rica are linked to improper relationships. However, there is an indicator that can shed light on the matter. In 2022, more than half of teenage mothers (52.5%) between 15 and 17 years old claimed they didn’t know the age of their child’s father, while a third (28.9%) didn’t declare the father.

“These numbers worry us because we’re talking about percentages of births in which the girls say that they aren’t going to comply with the Paternity Law and they aren’t going to provide evidence if they are in a situation of violence,” said Evelyn. This legislation allows mothers to declare the father of their baby – born out of wedlock – so he legally assumes his shared role and responsibilities in pregnancy expenses and child support.

On the other hand, Law 9406 of the Penal Code establishes that an improper relationship is a relationship of power established by the age difference, which can be 5 years difference when girls and boys are between 13 and 15 years old, or 7 years difference when they are between 15 and 18 years old.

This law – in force since 2017 – is a result of an investigation carried out by UNFPA with data from the 2011 census. Among the investigation’s findings, the organization found that of the girls between 12 and 14 years old who reported being in a common-law marriage, about 89% lived with a man at least 5 years older than them, while among adolescents (between 15 and 17), this percentage was 72%.

In addition, the data show that three out of every four girls and adolescents who lived in a common law marriage did not attend school and that six out of 10 already had at least one son or daughter. “Many times what the system does is blame the girls, when instead the challenge is to give them a vision of human rights. These girls are in a more vulnerable situation, maybe they’re not going to have a pension and they’re close to reproducing the cycle of poverty,” added Evelyn.

***

The faces of violence

Sharon is terrified that any of her six children will go through what she went through.

The first time she was sexually abused, she wasn’t even seven years old yet. It was her uncle, in Nicaragua. Her body froze and she didn’t know what to do except to remain silent. The second time she was sexually abused, she was 13 years old, already in Costa Rica. It was her maternal grandfather, with whom she had immigrated to Costa Rica. When Sharon told her grandmother, who had raised her since she was a baby, the response left her stunned and with a shadow of helplessness covering her soul. “It’s a temptation from the devil,” she told her. “It happens to anyone.”

“I never thought that someone’s family could do that to them. I loved my grandfather as if he were my dad,” Sharon says. However, the third time she suffered sexual violence, it wasn’t a family member, but rather a man who, in her own words, “took advantage of her need.” A man who offered her money that she couldn’t refuse because that day she had ended up alone, she was far from her home and she didn’t even have a cent. “I even dream about that person. Even one of my daughter’s teachers, to whom I had never told that secret, suddenly reflected on it and told me that she could tell that I’m suffering and it’s true. I can’t even sleep at night because I have that idea. I can’t forget it,” Sharon says as one of her daughters hangs on her legs again and again, begging for attention.

She doesn’t know what to call what happened to her that day when she felt so helpless and tarnished. In coastal provinces such as Guanacaste and Puntarenas, peak tourism seasons, gentrification and harvest times for crops such as melon, coffee and sugar cane increase women’s risk of falling into sexual and labor exploitation networks. This has been documented by David Ruiz from the Warnath Group, an American organization that has been working for more than 20 years on human trafficking in different countries around the world.

“In Guanacaste, there are mixed migratory flows due to the proximity to the border and many take advantage of the vulnerable condition. This is due to the irregular legal situation that some of the immigrants have. We have had cases in which trafficking networks recruit in Nicaragua and sexually exploit people in some bars and restaurants in Costa Rica or, for example, they catch people who come in a vulnerable condition and promise them a house where they supposedly are going to give them shelter and food,” he added.

David also says that human trafficking “is more domestic. It occurs in the family, it occurs in homes, it occurs in communities, it occurs even through the people who are closest to the victims, people from whom trust and protection are expected.”

***

Sharon lives in a one-bedroom house with just one bed. The day she talked to The Voice, she was wearing a blue spaghetti-strap top that showed off the well-defined collarbones of her slim body.

With her long fingers, she points to a corner – as if she were drawing other places with her mind and conjuring them up out loud – and says that here is the place for the TV and there is the kitchen and over there is where the clothes are kept. She puts her hands on the bed and says, “I sleep here, the baby here, the little girl here, one of my boys here, my partner here.” When night falls, the bed becomes infinite. She sends her other children to sleep with a sister-in-law who lives nearby and who also helps her from time to time with food for the children, when their situation is difficult.

At three in the morning, she can feel the baby searching for her breasts. According to WHO, a breastfeeding woman should consume a minimum of 1800 calories a day, depending on her physical activity. Although Sharon prefers to endure hunger so that her children can eat, milk continues to flow from her breasts so that the girl continues to have round cheeks, strong lungs and a vibrant heart.

The family lives in Martina Bustos, a community located 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) from Liberia, which is distinguished by its limestone land, sometimes so white that it dazzles as if it were snow. The community is named after the woman who owned those lands, a 23-hectare (57-acre) property that she wanted to donate so that people who lived in poverty could have land and build a decent home. The donation was never legalized and that’s why, even though there are families who have lived there for more than 25 years, Martina Bustos is considered an informal settlement. Many of the community’s residents are of Nicaraguan origin.

Sharon appreciates having that space. While there, she got a job – in addition to her six children, she takes care of her neighbor’s four children. Her husband is unemployed. She is the breadwinner of the home.

While the voices of her six children and one of the children she cares for flow around her, demanding a glass of fresh water, a change of clothes, a moment of listening, Sharon talks about motherhood, trying to do many things at the same time. time. Kenza, her eldest daughter, takes the youngest in her arms, Charlyn, a baby just one month old who seems to want to shake off the stifling feeling with a tiny, almost timid cry. Kenza is nine years old and is already learning to take care of kids. She knows how to get rid of colic and has a special ability to make her sister calm down and sleep.

Sharon wants Kenza’s path in life to be completely different from hers. She already talks to her about it. She tells her to be careful, to study, to be a good girl. And Kenza listens to her. She likes math and dreams of going to university.

“The longing that one has as a mother is to help them get ahead, to recommend that they study, to give them advice and to continue on their path, that they don’t give up their studies for things on the street like I did, because sometimes you feel like you regret not having studied because you don’t have a good job. So, to keep myself well, I fight for my children,” she says in her gentle voice.

***

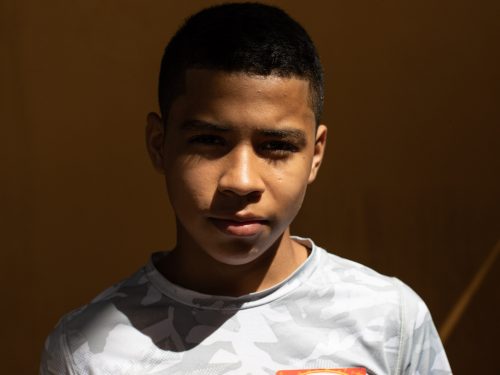

When Melany realized she was pregnant, she went into denial. She was 14 years old and, with the help of her friends, she searched the internet for different natural remedies to abort the pregnancy. She made mixtures of different herbs and drank the concoction several times. As a last cry for help, she also mixed medications and looked for a secret clinic in San Jose, but she didn’t have the means or the confidence to go that far. She knew the risks. When she reached the third month of pregnancy, she accepted what was coming – she was going to become a mother.

Six months later, her water broke early one Monday morning.

“When we got to the hospital, my mom asked if they could do a C-section because I was 15 years old and I’m small. I felt like I wasn’t going to be able to have it. Then my mom asked if they could do a C-section and they told her no, that I had already gotten myself into that and that I had to have it, that I had to endure.”

But if it was about enduring, Melany had already done that for a while. She remembers that she was first taken to the Filadelfia Clinic, where she says she felt like they didn’t believe her when she told them that her water had just broken. “They told me I still had two weeks left.” She waited two hours until her mother decided to take her to the hospital in Liberia, where she had to endure another 10 hours for her baby to be born naturally while – she felt – the health professionals who were assisting her repeated that “if she had gotten herself into that, she had to endure the consequences.”

According to the National Survey of Women, Children and Adolescents published in 2018 by INEC, 58% of women who had a vaginal birth or a cesarean section between 2016 and 2018 reported having suffered some type of obstetric violence.

The first day Melany was alone in the house with her son, three days after giving birth, she froze, staring at a wall. She had no idea how to become her child’s mother. She didn’t know what to do if the boy started crying. She didn’t know if her arms were going to have the ability to imitate the rhythm of someone who knows how to rock such a small baby to relieve colic or make him smile for the first time.

From then on, she felt depressed. “I got postpartum [depression],” she says. It hit her so deeply that at some moments, she thought about ending her life. “Imagine, [being] a girl, a teenager and a mother with postpartum [depression]. There were a lot of things [going on in] my head. I thought that one day I was going to throw myself in front of a car,” she says now, far from the person she was in those days.

One of the most difficult things about those first months was breastfeeding. In-person classes had resumed after the COVID-19 pandemic. Melany walked from her house to the high school and stayed there all day. She could feel how, little by little, her breasts were filling with milk. She was learning not only to fulfill a new role, but also to endure the physical and emotional pains that only mothers know. When she couldn’t take it anymore, she would run to the bathroom, a set of five toilets shared by more than 600 women at her school. And right there, in the midst of the teenage tumult, she squeezed out by hand the warm liquid that her son couldn’t drink.

Melany is 17 years old and is Costa Rican. She doesn’t have a story of immigration like Carmela and Sharon, but the three of them are connected by the challenges faced by women who have babies as girls. The social stigma. The lack of opportunities. Violence in all its crudeness.

***

Sharon says she wanted five children but she had six. When she left the hospital in Liberia after giving birth to Charlyn, she was told to return in four months to have her tubes tied and make it clear to her body that she won’t give birth anymore. If she could have chosen another path, she would have liked to be a police officer. “Police or security guard, that seems nice to me. I’m sure you learn a lot.”

When she had Kenza, her first daughter, she was offered birth control pills, injections and condoms, but she lived far away and she didn’t have the financial means to travel to the hospital every month. For some time now, CCSS health centers have offered intrauterine contraceptive methods, such as the “Copper T” and subdermal implants, but the information necessary for young women to get these methods remains poor, distant, many times inaccessible.

Sharon speaks harshly about her history in front of her children. She is blunt because she wants them to listen to her and not repeat what she did. If they don’t have enough information at school, she tries to give it to them, mainly to Kenza who is already approaching puberty. “When Kenza was born, I saw her and hugged her and kissed her. I told her that I was going to give her all the love that they never gave me… I am giving love to my children and I am always looking out for them, what they lack and what they don’t lack, making sure no one touches them. I’m always watchful,” Sharon says like a defiant lioness, defending her cubs.

Kenza is slim, agile and eloquent. She has a completely shaved head and a purple skirt that covers her knees. She has big eyes and very white teeth. While she cradles her little sister in her arms, she says that she also dreams of being a mother, but she doesn’t want it to be soon because she likes going to school and eating soup with meat in the cafeteria. Her mother listens to her and smiles.

Sharon doesn’t remember how old she was when she crossed the border, but she hopes her children never have to immigrate to find a better life. Sharon pushed every time she had to and with all the strength in her soul to bring them into the world, but she hopes that her children can make decisions that are different from hers, that they have the tools, the knowledge and the drive to create a brighter, less uncertain path for themselves.

She left school when she was 12 and “took to the streets.” As a teenager, she learned to be a mother and being a mother, she learned to dream. For her and for her children.

This research was supported by the Consortium to Support Independent Journalism in the Latin American Region (CAPIR), a project led by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR).

Comments