It’s Monday, May 27, 2019 at 6:02 p.m. and reporter Daniel Dinarte creates a poll on his Facebook page Dinarte Noticias DN, asking followers for which of two femle precandidates for mayor in Guanacaste they would vote. The poll includes a photo of each of the two candidates and it has 48 comments.

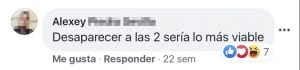

“I know one of them and she is excellent, but no. She’s prettier when she stays home,” says a man in one of the comments. Another adds, “making them both disappear would be the best.” Former Santa Cruz representative and Broad Front party member Carlos Zapata, the Dinarte journalist and five others react to the post with likes, smiley faces and hearts.

Comments like this that threaten females who aspire to political posts are just some of the many types of violence that female politicians face. It’s called political gender violence, a term that was born when women started to take positions in a field historically dominated by men and where they have found unequal treatment and opportunities.

When confronted by The Voice, Dinarte says the comment was made by a friend of his and that it’s not extreme, but sarcastic. That’s why, he says, he reacted with a “like”.

The extremist thinking of millenials and progressives is what has us in the state we are in, thinking that everything is violence and chauvinism. That’s concerning,” he says.

“There’s no such thing as a joke anymore, no more black humor, no more sarcasm,” he said via phone.

We also wanted to understand Zapata’s reaction, so we sent him a message on Facebook but he didn’t respond.

According to experts, these men aren’t attacking them for their political views, trajectory or their abilities as candidates, but because they are women.

Yensy Herrera, sociologist for the National Institute of Womens’ Affairs (Inamu), says “these are comments that they wouldn’t make to male politicians but they do to female ones. Things like, ‘what are you going to do with your kids?’ Or, ‘aren’t you afraid of divorce?’ It must be recognized that political violence exists and the problem isn’t the person or their capabilities, but the fact that she is a woman,” Herrera says.

Political gender violence also happens when party leaders intimidate elected female officials, or when a mayor assigns basic jobs —like being a secretary or assistant— to a female deputy mayor, according to the model law regulating political harassment and violence, written by the Inter-American Committee on Women at the Organization of American States.

They still view us as guests in a place that isn’t ours,” Herrera said. “That’s why in political gender violence there’s the intention to limit female participation in political posts.”

Bolivia is the only country to adopt a law penalizing political violence and harassment against women. It was approved in 2012. Other countries like Mexico created a protocol so that women know what to do when faced with these situations. Costa Rica doesn’t have any relative regulations on the matter.

Costa Rica’s electoral authority (TSE) doesn’t use the term “political violence” because it doesn’t have a statute defining it, says attorney Juan Luis Rivera. When electoral injunctions or complaints are filed, they only examine whether or not the official is being deprived of her right to work or not.

In the past, they tried to create specific regulations, but such attempts failed. In the last two legislative periods, bills have been presented but never advance beyond the Special Permanent Committee on Women.

Awaiting regulation, women in politics continue working without clear tools to deal with threats on social media or performing tasks below their paygrade. Demanding justice is even more difficult for those who aren’t able to recognize this as a type of violence of which they are victims.

Shari Avendaño, Venezuela. Data journalist, fact checker and illustrator. Member of The Verification and Fact Checking Unit for Venezuelan online newspaper Efecto Cocuyo. She loves colors, comics, trips and sweets. @shariavendano

Political Parties are Enemy #1

The fact that a former representative liked one of the violent comments against the candidates isn’t an isolated case. Political parties continue to treat men and women unequally.

Patricia Mora, a former Frente Amplio (Broad Front) party lawmaker who is now president of Inamu, says she has dealt with inequality. She recalls, for example, when political party events were held at times determined by men. “It overlapped with the time that I put the girls to bed or when I had to get them on a bus to send them to school,” she says.

“Women haven’t been given space in politics. We have to break down doors in order to get in.”

Breaking down doors, as Mora says, led to the TSE establishing some requirements for parties, like parity and alternation of candidates in Congress. That means half of candidates must be men and the other half must be women (parity) and they must alternate male-female or female-male (alternation).

But this hasn’t been enough to achieve equality. In February, the TSE issued a resolution — with one vote against it from magistrate Eugenia Maria Zamora — stating it won’t require parity quotas for 2020 municipal elections.

Marcela Piedra, political analyst and researcher at the Political Studies Research Center (CIEP), criticized the decision. She also says people criticize equality quotas, arguing that women reach political office exclusively through such a mechanism.

“That’s not the case. Women win because they are citizens, because they are half the population and because they have rights,” she says emphatically. “Parity has been the mechanism for making it fair.”

And Once in Power?

When they reach political office, women often encounter difficult terrain. Inside city halls, for example, some male counterparts ignore them when they speak, interrupt them or turn off their microphones during city council meetings, according to testimonies collected by Piedra, the analyst.

Even in power, doing your job, you have to elbow your way through,” says representative and Liberia mayoral candidate Alejandra Larios.

She has experienced discrimination for things that have nothing to do with her political party or work as a representative.

In one council meeting, for example, a citizen who gave a presentation provided all the men with material, but not her. “He didn’t even look at me during his presentation,” Larios said.

She told her colleagues that she wouldn’t vote for the proposal because she wasn’t important to the presenter. But beyond complaining, female politicians don’t have a clear path forward for denouncing violent and discriminatory treatment.

“Sometimes we don’t file complaints because we are afraid, or because we think it’s not violence or that it’s not bad,” Larios says.

Deputy mayors also face political violence frequently. The latest reforms to the municipal code state the functions of the deputy mayor’s office will be determined by the mayor. “Simply put, you wouldn’t think that it would create a problem,” says the CIEP expert. But in practice, cases of harassment and violence toward female deputy mayors arose.

“They are assigned absurd tasks like verifying what time officials arrive and leave work, or they aren’t given computers or resources and are pressured to resign,” Piedra says.

According to Herrera from Inamu, they are hoping to force them out of the political arena, which carries a cost for everyone. If only men govern, there is no guarantee womens’ needs are met.

If we are going to build a park, it needs to have enough light for women to feel safe and its construction can’t be just through a man’s eye,” she says.

A Labyrinth with a Dead End

The only cases of this type of violence in Costa Rica have been filed through electoral injunctions where female politicians explain they aren’t able to do their jobs. Inamu advises women when they want to file injunctions.

“There aren’t many formal injunctions relative to how much women talk about it,” Piedra says.

One of the few politicians who has used the electoral injunction is Santa Cruz mayor María Rosa López.

When she was deputy mayor, López alleged the mayor gave her a job without anyone to help her perform its necessary functions and he would make negative comments about her on social media, such as saying he was going to “send her to the freezer,” suggesting he would leave her without any responsibilities. The injunction was tossed out.

They didn’t have the capabilities to investigate what was happening, López said.

Now, as mayor, she says she faces other situations that, for a lack of evidence, haven’t been investigated.

“A car followed me and I had to look for a safe place with people around. Then someone told me, ‘you better be careful and take different routes everyday,’” she said, convinced that a group of political opponents wanted to force her out of her post.

López was one of the candidates pictured in Daniel Dinarte’s Facebook post.

“Without a law, there is a void. We need bylaws that assign accountability,” says Herrera, from Inamu.

Comments