Four years ago, as soon as the local government officials for the 2020-2024 term took office, the vice mayor of Carrillo, Isabel Francina Uribe, hurried to organize a meeting with her fellow female elected colleagues in Guanacaste. They met on June 24, 2020 in the Municipality of Carrillo and since then, they formed a WhatsApp group called “Guanacaste en tacones” (Guanacaste in high heels).

“Colleagues, you are going along a route on which, at the end of the road, you’re going to have legal support. I had zero. I didn’t have any legal support [when I started],” Uribe remembers telling them. “Know that if at any time, actions and situations like this begin to occur, you are not alone.”

Uribe was referring to the approval of Law 10,235, the law to prevent, address, punish and eradicate violence against women in politics, which came into effect two years later, in May of 2022. The legislation seeks to combat actions or speeches against women in public service that undermine the recognition and exercise of their political rights.

Her and her newly elected colleagues’ hope and enthusiasm was a temporary joy. Two years after the law was published, six of the 11 municipalities of the province still haven’t made a regulation for it, a necessary step for the institutions to establish how to punish violent expressions against women.

That’s why women in local governments — both popularly elected officials and any other civil servant — continue without a clear path to file complaints and request penalties. The story is different in Hojancha, Tilarán, Cañas, Bagaces and Liberia, which have already made it official.

The lack of budget allocated for publishing the regulations in La Gaceta (the Gazette) or the lack of political good will of the municipalities and the municipal councils of La Cruz, Liberia, Carrillo, Santa Cruz, Nicoya, Nandayure and Abangares coincided so that even today, the law is a piece of paper without clear consequences for those who fail to comply.

In a letter, the mayor of La Cruz, Alonso Alán, had justified not publishing the regulations — already approved by the council — alluding that it’s an expensive procedure.

“The costs of publishing in La Gaceta are extremely high when it comes to long documents like the regulation in question, which is around 1.25 million (about $2,400) for the 2 law publications,” he wrote. “This forces us to prioritize the documents to be published according to their cost and the cash available at the time.”

In Nicoya, council member María Auxiliadora Pérez affirmed that “it’s not a budgetary issue, but rather a bureaucratic issue.” Pérez is part of the legal commission, where creating the regulation is stalled due to a saturation of pending issues, she said.

Super sad, but in all honesty, I believe it will be left to the next council [which takes office in May],” added Pérez, who experienced political violence first hand two years ago by a fellow council member of hers who told her in a public session: “I was writing a message to you but it was better that I deleted it, since you are a woman.”

In Liberia, Vice Mayor Arianna Badilla was the one who pushed for the council to approve the regulation.

“This law cannot be executed by itself, but rather, there has to be an internal regulation that is the basis of the law,” she told The Voice in her office in the Municipality of Liberia, where Mayor Luis Gerardo Castañeda relocated her when they began to have friction between them a year after they had taken on the municipal administration together.

“It’s the municipal council itself that’s responsible for carrying out the disciplinary procedure,” explained the chief of staff of the presidency of the Supreme Election Court (Spanish acronym: TSE), Andrei Cambronero. “And if, only if, that council considers that the offense warrants the removal of the offending person from office, then the matter is transferred to the Supreme Election Court,” he added.

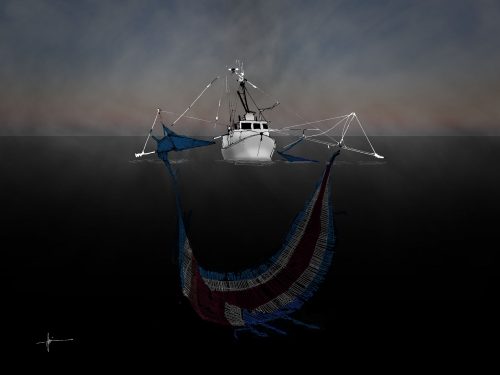

Pie 2: The female officials elected by popular vote gathered together on June 24, 2020 in a meeting promoted by the vice mayor of that canton, Isabel Francina Uribe.Photo: Facebook of vice mayor of Liberia, Arianna Badilla

In and out of the hallways

Isabel Uribe, Carrillo’s vice mayor, who promoted that meeting and the “Guanacaste in high heels” chat, has been the vice mayor of the province who has raised her voice the most to denounce political violence.

“It’s a monstrous situation,” described Uribe, who was incapacitated for a month eight months before that meeting due to depression associated with her work. Although she had duties assigned by the mayor, Carlos Cantillo, she feels that her work was purposely boycotted to tarnish her as a political figure.

“On many occasions, my salary was the budget to carry out the projects,” she said indignantly.

She affirms that she was not invited to activities of the mayor’s office, she was not notified of the mayor’s periods of absence, when she was the one who should assume the responsibilities and powers, as established by the Municipal Code.

On one occasion, they even cropped her face out from a group photo published on the municipality’s social networks.

And as was predictable, the local government was inundated with comments.

“And the rest of the photo? Or by chance did they not realize that there were other municipalities that took the same photo and published it in full?” demanded a citizen in the comments. “Why did they cut out the Vice Mayor? We’re still in the stone age, minimizing the work of women,” said another.

In an interview with The Voice, the mayor of Carillo, Carlos Cantillo, said that that was the photo shared with him by a female official from the Municipality of Liberia who took the photograph. And then he asked the person in charge of social media for the Municipality of Carrillo to post it.

Cantillo also shakes off Uribe’s accusations, saying that he has felt “that she has wanted to be the figurehead of the institution, when I am the mayor.” He also alleged that whenever he could, he “ran” to obtain the necessary budgets for the projects she promoted, and that if another official acted as a leader in his absence, it was because she was in “ignorance,” he said, of the municipal procedures.

Name violence to recognize it

Costa Rica joined 11 Latin American countries that have legislation against belittling women in politics.

With this law, Congress officially introduced the recognition of this type of gender violence in the State’s public institutions. Political parties also should have created internal policies, and propaganda messages promoting violent or stereotypical messages are prohibited.

The legislation condemns a list of actions that range from assigning women tasks that do not correspond to the investiture or hierarchy of the position, to preventing access to information necessary for carrying out tasks and undermining their political capacity due to their gender status (see from article 5 on in the link of this image).

Fear of competition

Before the legislation was published, not even the TSE recognized political violence in the appeals for electoral protection that popularly elected female officials had filed since 2011 when they felt their political rights had been violated.

“[The appeals are filed] particularly by vice mayor’s offices, which were and are mostly occupied by women, in which they alleged that, due to gender, the person who held the mayor’s office had manifestations of political violence such as not granting them functions or undervaluing their work,” explained TSE official Andrei Cambronero.

“However, over time, the TSE did not pronounce any ruling in which the situation of political violence was recognized as such.”

The vice mayor of Liberia, Arianna Badilla, is the only vice mayor from this term in the province who has presented appeals for electoral protection due to political violence. She filed one before the law was passed, and another after the legislation went into effect. In both, she has claimed that the mayor eliminated functions that she had previously been assigned.

The mayor that the appeal was filed against [Luis Gerardo Castañeda] reduced the functions of Mrs. Badilla Vargas without justifying that decision,” the judges concluded. “It is proven in the file that the tasks that she retained are insufficient to adequately exercise the first vice mayor’s office.”

Both Badilla and Uribe believe that one of the mayors’ main annoyances was perceiving that they also had ambitious political projects. Both, in fact, wanted to aspire to become mayors.

Uribe, however, wasn’t given the chance because her candidacy was going to be with the Aquí Costa Rica Manda (Here Costa Rica Rules) Party, which the TSE stopped due to non-compliance with the requirement of gender parity in municipal candidacies.

To the TSE chief of staff of the presidency, Andrei Cambronero, it’s necessary to further socialize the paths that should be followed to “be clarifying when to resort to one instance or the other.”

The multiplicity of doors that the law generated so that women can see their rights protected were many and it’s necessary to be appropriating this law so that there being various forms of protection or guardianship does not become a difficulty of access, because I don’t know where to turn,” he added.

The vice mayors of Liberia and Carrillo also think that even a reform of the Electoral Code should be considered, so that the functions of the vice mayors do not depend on the decision of the person holding the position of mayor.

Both also question the correct application of the law, since in the municipalities, the municipal councils are the ones that must apply penalties. And what happens if they are completely aligned with the incumbent mayor, Uribe questions.

Comments