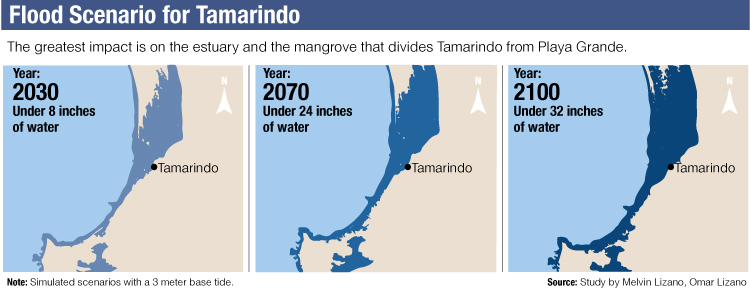

By the year 2090, the estuary and mangroves that divide Tamarindo from Playa Grande will be flooded under at least another meter (about 3 feet) of water. Researcher and oceanographer Melvin Lizano, from the University of Costa Rica (UCR), detailed this in a study that is about to be published.

The increase in sea level will occur gradually and continuously, the study says. By 2030, the flood level will be 20 centimeters (about 8 inches), increasing to 30 centimeters by the year 50 (about 20 inches) and to 82 centimeters by 2100 (about 32 inches).

But you don’t have to wait 80 years to see evidence. In Tamarindo, trees along the coast with their roots exposed reflect a process of erosion and sedimentation with almost no reversal. This is an indication that the rise in sea level is already affecting the coast.

According to the UCR researcher, the beaches that will not suffer this type of effect in the next decades will be few. For example, the study also paints two other flood scenarios in Guanacaste: Los Mangos (also known as Torito) and Cambute in the Samara district, and the center of Playas del Coco.

The main cause of this behavior is the planet’s temperature increase, which ends up melting the large blocks of ice at the poles called glaciers, said Lizano. “You have a glass of water that is almost full. Grab an ice cube and throw it into the glass. An hour later the ice melts and the water overflows. It’s the same mechanics in the sea,” the specialist added.

The world’s oceans have never been as warm as they are now. The most recent study published in the journal Advances in Atmospheric Science, conducted by 11 scientific institutions in China and the United States, reveals that climate change took ocean temperatures to a new extreme in 2019.

The amount of heat we have put into the world’s oceans in the last 25 years is equivalent to 3,600 million atomic bomb explosions like the one in Hiroshima,” indicated Lijing Cheng, lead author of the study.

How Coasts Are Protected… For Now

“Currently, Tamarindo’s ocean is sucking away the sand, leaving the coast with less and less material,” explained environmental issues consultant Daniel Loria, who conducted a study of ocean behavior at the request of the coastal hotel Capitan Suizo.

Although the study does not take into account climate change variables, it is a guide for understanding future scenarios.

Capitan Suizo’s hotel development manager, Urs Schmid, perceives that the 50-meter (164-foot) public area between the hotel and the beach is decreasing little by little, which has long term economic as well as environmental consequences.

“I know of several hotels and restaurants that are having the same problem and are trying to do something in some way,” Schmid commented.

The hotel decided to protect the coast’s trees and the building with a wall of tree trunks that is supposed to break the strong waves. Although they tried to apply for a permit to build a retaining wall (usually made of stones and metal mesh), the municipal council rejected it because they are in the maritime land zone.

Other community residents, business owners and locals are also replicating the log wall to mitigate the impact of the waves.

We know that any construction in the maritime land zone is a sensitive issue for the municipality, but [the council members] only denied the permit and did not think of a solution beyond that,” the manager commented.

Like Water for Your House

The scenarios that Lizano, from the UCR, paints in his study are blunt: the coast as we know it won’t be the same in 10 more years.

“The sea will reach areas where it didn’t before. We know that geography will change according to simulations with current data, data that could change and further aggravate the situation,” commented the researcher.

For the three areas studied, flooding will begin at the estuaries and river mouths, and will continue advancing.

“Whenever there is an estuary area, the water enters there and the level begins to rise. If the estuary becomes full, then the water will look for where it can drain the easiest,” explained Lizano.

The report indicates that flooding in these communities will not only be linked to an increase in ocean temperatures, but also to other natural behaviors such as the El Niño phenomenon or storms out at sea, which could intensify with climate change and complicate the panorama even more.

Neighbors and hotels make walls out of logs in front of their buildings to curb the effects of strong waves.

Patches As a Solution

The researchers consulted for this report agree that local governments must start working now in order to minimize the future impacts on both businesses and coastal communities.

But the reality is very different. Santa Cruz, which has the largest coast in the province (with 94.5 km or 58.7 miles), has no plan. Onias Contreras, coordinator of the Maritime Land Zone department, admitted that he has not planned or discussed any projects on the impact of climate change on the coast. Therefore, the department is not taking actions to minimize the risk to the inhabitants.

“We do participate in meetings with other organizations that cover these types of issues,” said Contreras.

Other institutions, like the Guanacaste Chamber of Tourism (Caturgua) recognize the need to understand and attack the increase in sea level to minimize impact on the main economic activity of the province: tourism. However, the efforts remain in macro training, according to the chamber’s president, Rebeca Alvarez.

“We have looked at the issue of drought and water use. In other words, general issues, not something as specific as the subject of coasts, ”Alvarez added.

Daunting Future

The challenge is adapting to the changes. And to do that, planning is essential, researchers Lizano and Loria acknowledge.

From their point of view, developing regulatory plans that take into account scenarios of rising sea levels would be the most efficient solution. But Lizano affirmed that, to date, no national plan does.

A regulatory plan is a document that permits land use zoning of an area (where you can build, establish a business or a public area, according to environmental needs), a canton or a coast. Municipalities can prepare them with the help of development associations and public-private partnerships.

These types of plans help municipalities to ask in which areas to give building permits or require changes in plans such as a house being built on piling or piers.

In Nicoya, the coordinator of the municipality’s Construction Control and Public Works department, Josue Ruiz, explained that the regulatory plan for Samara’s coastline was made in 1981, and since then it has not undergone any modification.

The local government currently has no plans to start a new regulatory plan process in Samara since it is currently working on the process for Nosara and Nicoya.

“Eventually there will be a crisis of drastic change affecting the public area that none of the municipalities see coming and that they are not contemplating,” consultant Daniel Loria commented.

In Santa Cruz, for example, less than half of the coast (35.5 km or 22 miles) has a regulatory plan. “We still have a good stretch of areas [of the coast] to concession due to the lack of regulatory plans. There is an administrative inability on the part of the municipality to implement them,” admitted Contreras, from the Maritime Land Zone department.

“How much money would we save if we had the culture of prevention?” Lizano concluded.

Comments