When Gustavo Marín assumed the position of principal of Nicoya’s high school this year in March, he immediately noticed that he had to do something to get the students away from drugs. Some skipped classes to go use drugs, others hung out in dark, isolated corners inside the school and others were seen in places near the school frequented by traffickers.

“When I started, we assessed the situation and we have detected about 40 kids who consume, out of a population of 1,069 students,” said Marín.

But we have implemented the policy of not kicking them out but rather of helping them, following up with them and empowering them with information on the problems of drug addiction,” he added.

He began coordinating with the Alcoholism and Drug Dependence Institute (IAFA), with the local Public Force and with the teachers and students themselves to respond to the problem. They created a network with institutions and educators to organize talks. During these activities, they look forward to explain to students the risks of using drugs.

Within the school grounds, they put a gate up so that the youths can no longer go out to a green area where they presume they used to go to use drugs and closed a hallway that they probably used for the same purpose.

It isn’t something that happens just in this school, nor in this canton. In fact, in the country, young people start using marijuana, cocaine and ecstasy at age 14, according to the latest survey on drug use in high school youth by the IAFA.

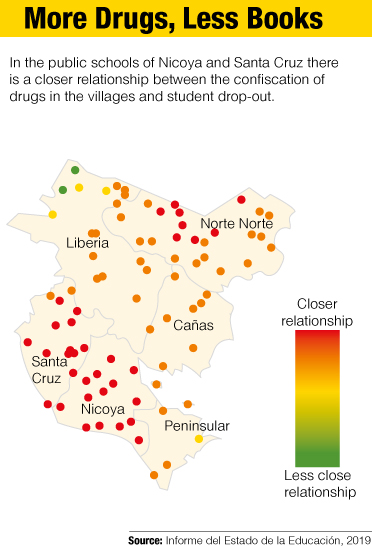

The educational centers in our province see drugs as one of their biggest enemies and it is not just a fad: Guanacaste and Limón are the provinces where there is a greater relationship between dropping out of high school and drug confiscation in the towns where they are located, according to the latest State of Education report, published in August of this year.

In other words, the closer the high schools are to places where drugs are seized, the greater the risk that students will abandon their studies.

In Guanacaste, the relationship is most evident in the school districts of Santa Cruz and Nicoya, followed by Liberia and Cañas (see map).

However, the problem is not just outside the school gates. During the first half of this year, confiscation of drugs in elementary and high schools in the country has already exceeded 2018 figures, according to the Regional Anti-Drug Program of the Ministry of Public Safety. As of July of this year, the police had already seized 128.2 grams of marijuana, 1.5 of cocaine and 0.4 of crack, while in the entire previous year they confiscated 87.5 grams of marijuana.

However, the problem is not just outside the school gates. During the first half of this year, confiscation of drugs in elementary and high schools in the country has already exceeded 2018 figures, according to the Regional Anti-Drug Program of the Ministry of Public Safety. As of July of this year, the police had already seized 128.2 grams of marijuana, 1.5 of cocaine and 0.4 of crack, while in the entire previous year they confiscated 87.5 grams of marijuana.

To draw conclusions regarding the relationship between confiscations and dropout rates, researcher Leonardo Sanchez analyzed the 2017 data on seizures or confiscation of drugs by the Costa Rican Institute against Drugs (ICD), the places where they occurred and data on dropouts.

That year, the ICD recorded 95,654 seizures throughout the country, in areas where there were 18,204 people under 20 years of age.

This figure reveals the level of exposure to the problem by part of the population in that age group that, in theory, should be being taken care of by the educational system,” Sanchez expressed in the report.

The investigation showed that 50% of the seizures in 2017 were located in only 33 of Costa Rica’s 385 districts. Put another way, half of the seizures are concentrated in 7% of all of the districts in the country. These districts have particular characteristics: they are heavily populated urban areas with an average poverty level of 23% and where 40% of inhabitants aged 25 and older only finished elementary school.

That does not necessarily mean that they are the areas where the most drugs are consumed, but rather those where more drugs have been seized.

In Guanacaste, for example, the districts with the most drug seizures are four of the most populated cities and they have more economic and social development: Liberia, Nicoya, Tamarindo of Santa Cruz and Sardinal of Carrillo.

The director of Nicoya’s highschool decided to close some dark and isolated places ehre students used to hang out. Photo: César Arroyo Castro

Young People Are Narco Targets

The researcher, the police chief of Nicoya and the various high school principals consulted by this newspaper agree that the educational institutions —and consequently the youth— are attractive to drug traffickers.

“The educational system, due to its broad coverage and density, forms a network that allows drug trafficking to have areas of attraction for buying, selling and distributing drugs,” Sánchez specified in his research.

The data backs this up. The report analyzed in detail 5,876 confiscations (out of 95,654 total) and found that 49.1% of the events occurred at a distance of 500 meters (1640 feet) or less from an educational center. Another 33.9% occurred between 500 meters (0,3 miles) and one kilometer (0.6 miles).

The principal of Nicoya’s high school said that they themselves have identified sodas (places to eat) and bridges near the school where drugs are usually bought and sold at the times when students get out of school.

These are places where strangers come to sell drugs to teenagers,” he related. That’s why the high school contacted the Nicoya police station so that they can patrol when school lets out.

“We coordinate so they do rounds and report the students to us, and yes, they have reported several to me who were with strangers,” he said.

Nicoya’s police chief, Omar Chavarría, affirmed that police data has also detected that the young population is a target pursued by traffickers. “They try to recruit teenagers as [drug] consumers, but also as distributors,” explained Chavarría. “Generally speaking, they are easy to convince and, in addition, with [teenagers], criminals are guaranteed to have long-term clients,” he added.

Chavarría also believes that methods for committing the crime of drug trafficking have evolved and that now, by means of smart phones, deals can be made without having to approach the schools.

Traffickers try not to expose themselves so that the police don’t locate them, and so they use social networks a lot,” explained.

A Persistent Problem

The principal of Santa Cruz’s high school, Jorge Arturo Alfaro, said that although he has noted that in his school, with 1,600 students, there is a group that uses drugs, they have not been able to find drugs with the canine police unit. “They probably leave it hidden somewhere,” said Alfaro.

Alfaro, the principal of the Liberia Laboratory High School and the principal of Nicoya’s high school believe that surveillance cameras have helped them exercise greater control over what teenagers do inside the school, along with the police officers who go in with dogs to find drugs.

These operations only take place when the schools request them from the Public Force. Nicoya’s police chief affirmed that it is important to measure the problem in the classrooms, but he thinks that education is the pillar to making young people understand the reality of getting involved with drugs.

“There are programs where we take in a lawyer who talks to them about juvenile criminal law, because after they’re 12, they can be charged with a crime, and we also talk to them about the negative consequences of drugs on the human body,” Chavarría explained.

In the high schools, they are looking for ways to counteract addictions. “It’s not just a problem with drugs, but also alcohol,” commented Marín, saying that they want to increase the number of cameras from the 16 that they have now to 40.

Comments