“Why are you carrying that gun?” Jamaican foreman Joseph Henry asked miner Juan Rafael Sibaja, when he saw him come out of a tunnel to pick up gunpowder in the Tres Hermanos mine. Juan Rafael replied that he was carrying the weapon as a precaution. That day, only he and his brother were working and they were afraid of going around defenseless if they had to face a conflict that might arise due to theft or drunkenness.

“You don’t go in,” the huge foreman warned him. He and other Jamaicans were hired as foremen by American businessmen. One of their main jobs was to search miners going in and out of the tunnels to prevent gold theft.

Juan Rafael didn’t obey and Joseph Henry kept his word. He tried to stop him in order to take the weapon away from him and during the struggle, the gun went off and hit the miner. The foreman ran to hide, but the damage was done. A group of union members began to crowd in, hungry for revenge against Joseph and the other foremen.

That Wednesday, December 20, 1911, is remembered in Abangares as one of the most important chapters in the canton’s history. Juan Rafael being shot was the starting point of a bloody day that left a “black cemetery.”

In addition to those deaths, dozens more died from drunken brawls, accidents in the mines or respiratory diseases caused by their jobs. “At that time in Las Juntas, what there were the most of were cemeteries,” remarked writer Santiago Porras, from Abangares.

The novels by this writer from Abangares as well as the writer himself critique and pay homage to Guanacaste’s beauty

In his book, Avancari, he narrates this confrontation between Jamaican foremen and the miners based on judicial documents kept in the National Archives. But before getting into how that shot began to paint a terrifying picture, we need to better understand what life was like in the mining mountains.

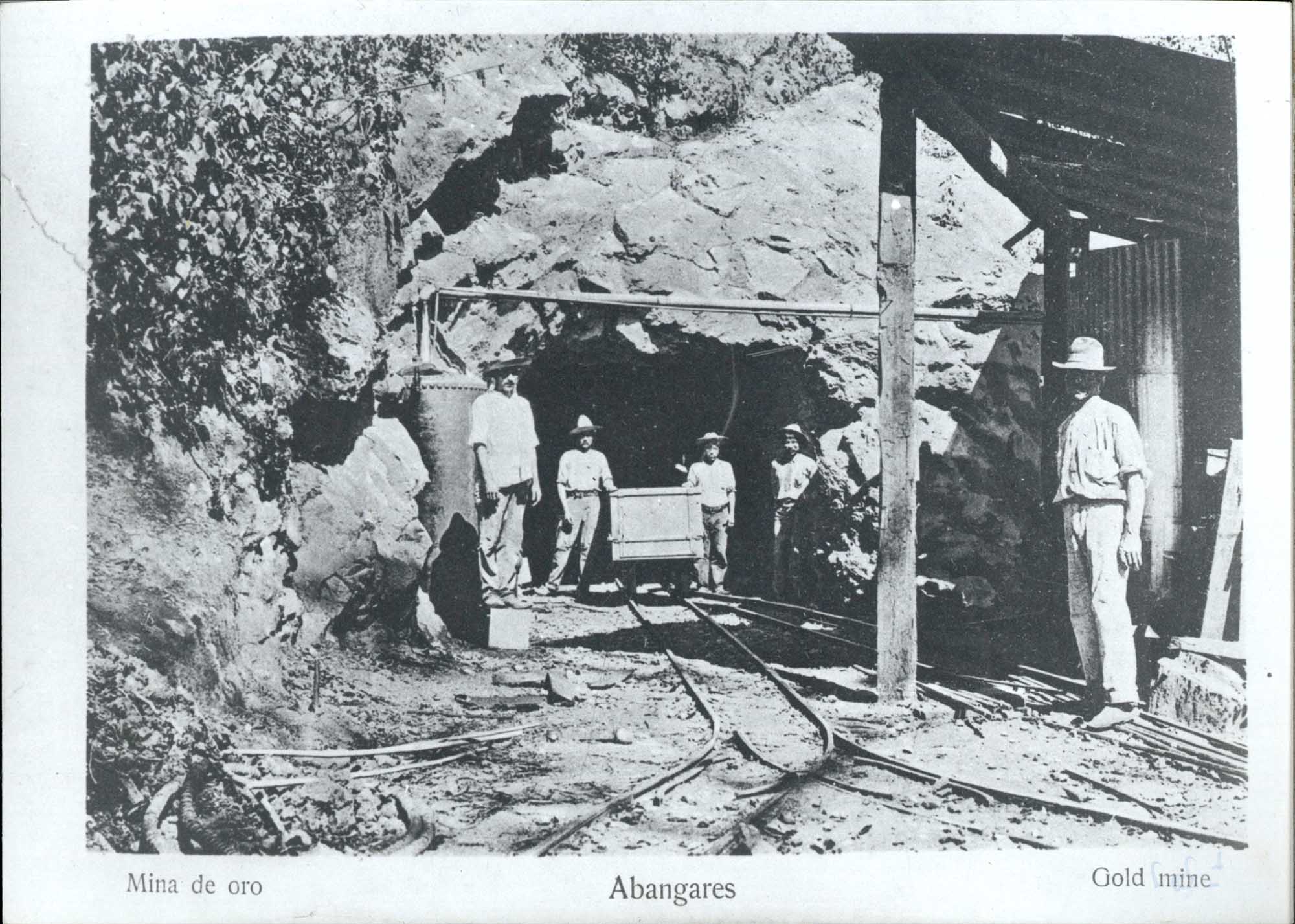

The Old West

Las Juntas was a small town located on the banks of the Abangares River, where there was normally not much going on. However, on paydays, hundreds of miners who had been underground in the tunnels in the mountainous area would come to town thirsting to get drunk, gamble or hang out in the canteens, dance halls and brothels on the main street.

The town would transform into a chaotic tumult. Merchants sold liquor in bottles, which often turned into weapons as well, when they ended up smashing them over each other’s heads.

The multiculturalism attracted by gold in Abangares was notorious: Central Americans, Americans, Germans, English, Jamaicans, South Americans and even Chinese. They were spread out among the Tres Hermanos, Boston, Gongolona, Sierra and Babilonia mines.

Miners were always looking to extract a small fortune from the mine without anyone noticing. When they found an especially rich vein, they saved small fragments of ore, forming their own secret reserve that they later ground next to a creek.

They used rags sewn around the body to hide the higher quality metal fragments. They also hid them in their shoes, in their hair and, in extreme cases, inside the rectum by means of a metal tube. They even came to the point of swallowing little lumps that they later recovered.

Jamaican Blacks

To control what they considered their wealth, the American leaders of the Abangares Gold Fields Company ordered the foremen to keep a strict eye on the workers.

Minor C. Keith, the company’s main shareholder, was responsible for bringing the Jamaicans from the Panama Canal, where they had been working. He had experience recruiting them for jobs in the region. He had previously brought other islanders to the Atlantic coast during railroad construction.

At night, when shifts ended, the foremen waited at the mouth of each mine for the miners to leave. They would stand in front of them and with gestures, they asked them to remove their clothes and probed their rectums with a stick to make sure they weren’t stealing gold.

There were about 50 Jamaicans working in the mines. Those who didn’t work as foremen worked as borers, chipping away at tunnel walls, or as cart drivers, transporting carts or wagons loaded with material.

One day, the company manager decided to pay the Jamaicans one peseta more per day, which upset the other workers, who perceived that the blacks were gaining more privileges and favoritism.

The Jamaican workers had better communication with the Americans because of the language. The Americans gave orders in English and they could understand them.

The company managers’ mandate to search the miners, and the abusive way in which the foremen carried that out, ended up fueling hatred towards the group of Jamaicans.

The Slaughter

After pulling the trigger on Juan Rafael, Joseph Henry ran to hide in one of the hotels where some high-ranking employees were staying, as well as relatives who came to learn about mining. Other black people immediately approached to support the foreman, including the cook, José Nicolás, and Pedro Rubio.

While Henry was hiding, other miners also began to form a crowd outside the hotel, including Gonzalo, Juan Rafael’s brother.

The enraged workers tried to open the door, but Henry shot, this time wounding Gonzalo. This further angered the miners, who managed to knock down the door, forcing the blacks to escape through one of the windows.

The miners caught up with Henry as he was escaping and killed him with bullets and the pointed end of the candle holders they used in the tunnels for light.

That death was no longer enough. The miners, armed with pistols and machetes, were determined to kill as many Jamaicans as they could.

José Nicolás had hidden in his house and the miners forced him out by threatening to blow it up with dynamite. He tried to defend himself by firing two guns until he ran out of bullets and they all ganged up on him and killed him.

Also among the dead was Pedro Rubio, a black Honduran who was brought by the company to serve as a policeman inside the mines.

Pedro was shooting anyone who came near from inside the commissary warehouse – a company storehouse where workers bought groceries. Another miner ran to the gunpowder shed, grabbed a stick of dynamite and crawled up stealthily to the commissary to throw the stick into the warehouse. Seeing the explosive, Pedro quickly opened the door and went out shooting.

The miners chased him and, once they caught him in a creek, they hacked him to death with machetes. He was so hated that one of the miners brought a dynamite stick, and when he was already dead, they put it in his stomach, took him to the bridge and dynamited him.

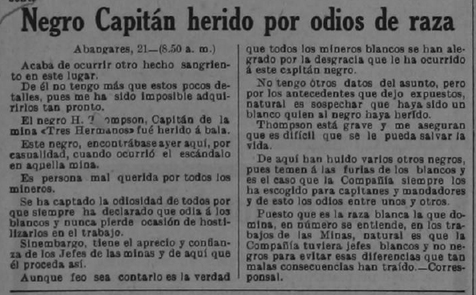

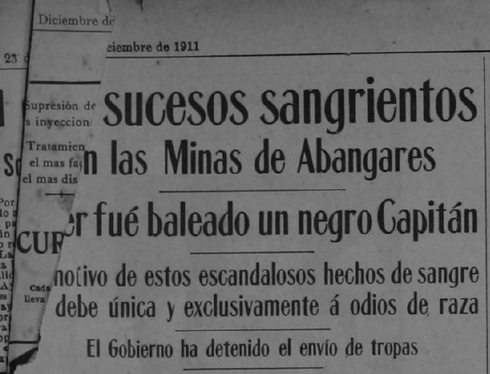

John Thompson, the captain and head of a crew of workers, managed to flee to Las Juntas, but while he was crossing the Abangares River, a miner saw him and shot him without thinking twice. For a couple of days, the national newspaper La Información headlined Thompson’s death as “Black captain wounded due to racial hatred.”

Company managers decided to evacuate the black foremen and send them to Manzanillo, a port about 25 kilometers (15 miles) away, on the way to Puntarenas. The plan was for them to travel to the capital and, as subjects of the British crown, request help from President Ricardo Jiménez.

The police didn’t leave headquarters and collect the bodies until they saw that the uproar had stopped. Some of those Jamaicans were buried in the Las Juntas cemetery. Others were buried where the bloodbath occurred, near the Pueblo Antiguo hotel in the La Sierra de Abangares district.

“Not so many years ago, there were remains of tombs, but people built and that disappeared. And that place was known as the “black cemetery,” describes writer Santiago Porras.

Yesterday’s News

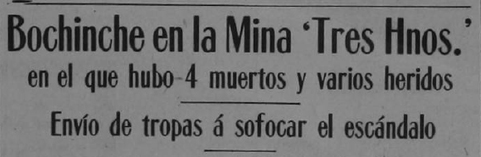

The first news was brought from the mountains of Abangares, where the massacre began, to Las Juntas by miner Pastor Mejía, wounded in the right arm. The newspaper La Información published the news on December 21 with the headline: Ruckus in Tres Hermanos Mine with Four Dead and Several Injured, followed by the following telegraph message:

“The agent found that made a kind of field of dissension. All of the revolting miners were armed with knives and revolvers and shots were heard everywhere. It is known that there were a great number of deaths; that black people fled in all directions.”

“At that time, the miners owned the mine. They seized the gunpowder from the warehouse and, armed with dynamite, entrenched themselves at the entrance to the roads in El Cerro de los Limones. Among the havoc wreaked by the rebels was that of blasting the La Sierra prison, the telegraph station and several more buildings with dynamite.”

Later on, the news article speaks of a “dispatch of troops to quell the scandal.” The commander and political chief of Cañas, Tayo Salazar, warned that he was going with 25 armed men. In addition, 10 soldiers and four armed officers with mausers were going from Liberia since the Las Juntas police commander only had a guard of 10 men to repress “an uprising of 400 or 500 workers.” During the night, he managed to double the number of officers thanks to the revolvers and machetes provided by the “senior employees of the [Gold Fields] Company.”

A day later, on December 22, the same newspaper headline read: Government Detains Troops it Sent Because it No Longer Believes Military Aid Is Appropriate. Although a couple of days later, everything returned to relative calm, the correspondent explained that he and “the main residents” of Las Juntas believed that the government should have “a good police guard permanently to avoid this kind of bloody scandals, even if they aren’t as serious as yesterday’s, they are frequent in these remote areas.”

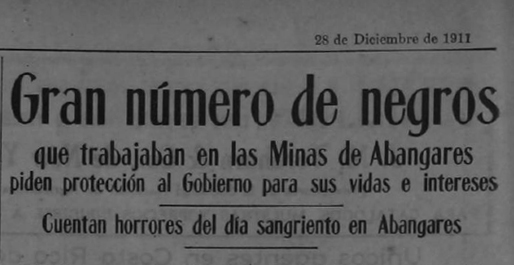

A week after the massacre in the mountainous sector of Abangares, La Prensa Libre and La Información published the news that 22 black people arrived at the Presidential House, fleeing from “persecution from white people” to ask the government for protection and tell about what happened.

The reporter interviewed several of the Jamaicans. “The white people have killed about eight blacks, that is known of, since many have disappeared and they suspect that they were killed in the mountains,” said one of them.

On December 29, La Información responded to a letter sent from Limón reproaching that the English consul, Mr. Cox, had not done anything to solve the situation of the Jamaicans, since that island was still a colony of the United Kingdom.

The newspaper responded in defense of the consul, affirming that he was looking for employment for the Jamaicans. The workers, on the other hand, wanted to return to the mines and although Mr. Cox considered it a bad idea, he affirmed that it was “the government’s obligation to offer them every guarantee for their lives and interests.”

The same article from La Información stated that “before convenience and interests comes the peace of the town and this is surely what the Chiefs of the Abangares Mines have thought, who for the moment are not willing to admit people of color to work to avoid new collisions between blacks and whites. And those gentlemen think well.”

____________________

This story was put together with pieces of other stories: newspaper articles, university publications, chronicles, memoirs and interviews:

- Graves and Chimeras, Miguel Salguero 1972

- The Abangares Mines, History of a Double Exploitation

- La Información newspaper, 1911

- The Gold War. Anthony Castillo

- The Gold Thread. José Gamboa

- The Mine Express. Ofelia Gamboa

- Interviews with: Santiago Porras and Elieth Montoya.

- Avancari. Santiago Porras.

Comments