A little over a year ago, a bullet pierced the head of Eleodoro Ramírez and took his life. He was killed while looking for gold that would provide him with enough money to buy food. He was killed, they say, for being a sucuchero, a name given to those who steal gold from others.

We are in the exact spot where this happened: the La Fortuna tunnel in La Sierra, Abangares. We walk 250 meters from the entrance to reach this point. There isn’t a single ray of natural light here and the only thing that breaks the total darkness is the light of a cell phone and a flashlight.

It’s a structure with rocky walls where dozens of small-scale miners, or coligalleros as they are called in Spanish, punch holes in the earth to find hidden gold.

Suddenly, one of the coligalleros starts to traverse the tunnel from the beginning to its deepest part, and each colleague he encounters warns him that they are about to detonate dynamite. Each one decides on their own if they want to stay or leave, as staying here during a detonation is an option for them. We, of course, make our way out.

We sidestep around the rocky points of the walls, the mountains of sacks accumulated along the sides and the multiple deep holes in the ground. We run into doors with gates and locks and several rundown bicycles which they use to transport material. For several meters our feet become submerged in brown water that, at times, reaches our ankles and even our knees. Eventually we are able to exit.

Outside of this, and the majority of tunnels and shafts, there are seats and spare car parts, tree trunks, dirt and piles of rocks. In one of the abandoned chairs, we run into two boys resting after a morning’s work.

“Why did you get into mining?,” we asked.

“Because there is no work,” answers Alonso, who says he is 22 years old, although he looks older.

“Leaving isn’t an option?”

“It’s hard. It’s hard to find work. If I could work somewhere else I wouldn’t be working here, because here is death,” he tells us in a serious tone while tightening his jaw.

After a bit of silence, Alonso says, “just by going down there, you are nearing death.”

All of a sudden, two loud booms rumble through the earth and our bodies. The explosives with which the are trying to deepen the mine has detonated.

“Not just anyone dares to go in there,” they tell us. But they do it as if it were a normal daily occurrence, as if their lives were worth less than ours.

***

It’s 5:30 am on Thursday, the first day of the month of February and, at the foot of the miners monument in Las Juntas, Abangares, there are dozens of men sitting around. They are waiting for cars, or small old cargo trucks to give them a ride to the mountains of this Guanacaste canton. They are going in search of gold.

Those who pass through here don’t pay too much attention to this scene. It is normal for them. But for the photographer and me, it has an impact on us to see so many men crowded together at this early hour, wearing dirty shirts, pants or shorts, knee-high socks and construction boots.

The mountains that these miners are going to are full of tunnels and underground shafts. There, everyday, they and hundreds more risk their lives to find gold.

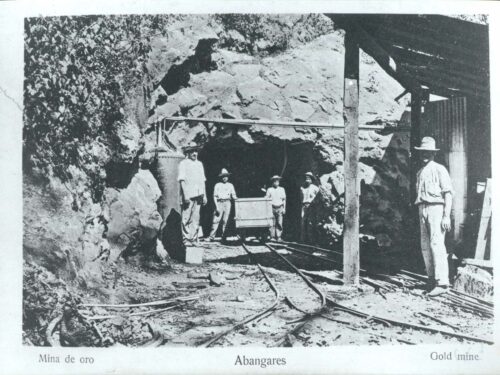

It’s a job that for more than a century has sustained many families in Abangares. For a large part of this century, foreign companies exploited the mines as well as the miners. When the price of gold crashed, the companies left and the territories were abandoned. The last of them left roughly 20 years ago.

The vast majority of those working around the monument avoid any questions about their work because it is so controversial: they use illegal materials like mercury and dynamite, they go on forbidden land and they mine without permits.

One of the few who agrees to talk to us is Diego, a cheerful 27-year-old kid with a tattoo on his arm. He tells us that his motorcycle is damaged, which is why, today, he is one of many waiting here.

In this atmosphere full of awkward looks, we feel that Diego is our only chance to bear witness to mining in Abangares.

While we speak with him, a guy comes to take him to work in the district of La Sierra, located roughly five kilometers (three miles) from here. We tell him that we want to go with him and he gives us vague directions as he hurriedly gets in the car.

***

After a search along the stony paths in the hills of La Sierra, we reach a shanty made of steel beams and metal barrels for a roof, with heavy sacks on top so it doesn’t blow away in the wind. Diego is here with six other men: Juan Taquito, Nino, Beni, Rodolfo and Kike.

In mining, some, like Diego, are laborers and others, like Kike, are bosses. What distinguishes them is that bosses have more mechanical means. In their homes or on other grounds they have rastras, machines built with car parts used to process the material and extract gold. Since this generates additional income for them, they hire laborers to help search for the gold.

On the steel beams at the shanty, the workers hang the bags that carry their bottles of water, utensils and food, which usually consists of half breakfast, half lunch. Here, everything is eaten at the the environment’s temperature and there is nowhere to warm up food nor a place to get fresh, potable water. In those same bags they have explosives and other supplies for detonations.

The seven men are around a shaft 50 meters deep and one meter in diameter where smoke is coming out. They just set off dynamite. They have been looking for and extracting gold from this very hole for six months.

“Dynamite is illegal, the same as mercury, but we can always find it and lots of it,” Juan tells us. “You get to know contacts that help you out.”

The authorities are aware of the covert sale of mercury and dynamite, but in the words of the Abangares Mayor Anabelle Matarrita, it happens without any control because no one knows who is responsible for regulating this market, not even the Mayor.

The coligalleros explode dynamite —and consequently they aggravate the stability of land— because material with a good amount of gold is increasingly difficult to find.

The man in charge of this task descends to the deepest part of the shaft and, after lighting the fuse, a race against death begins. He climbs up a ladder made of metal construction bars, some of the rungs broken. With one wrong step, anyone could be the victim of a fall toward the explosion.

“There was plenty of time to get out,” Juan tells us. Kike says that “plenty of time is like two minutes,” as he laughs before his look quickly becomes serious. “About 15 years ago a boy lit the fuse and no one knows what happened exactly, but the ladder broke and he fell.”

The man died as they die here, because of explosives, bullets, loose rocks or landslides that burry them. It’s normal, they say. Nobody other than themselves and their families notice the deaths.

During the conversation, they tell us that, with the exception of Diego, no one buys medical insurance or has a pension plan for the future.

“It’s not even on anyone’s mind, paying for insurance,” Nino says. “If you thought about it you’d realize that it’s important.”

Sometimes it seems that these men are only aware of what their job implies when someone from the outside asks them about what they do.

“I voluntarily pay for insurance because I have two children and one on the way, the old lady and the old lady’s grandmother,” Diego says.

What ends up happening in mining is that, at least for the laborers, the money is never enough to think beyond basic daily needs. Each one of them makes ¢80,000 ($140)per week. And when someone strikes it rich and finds a hefty quantity of gold, the majority of miners spend what they make from it on parties.

“Money is meant to be spent! Family first and what’s left is to take a spin around town,” says Diego, who started to mine eight months ago, when his partner got pregnant.

While we speak with Diego, Kike and their colleagues, the smoke dissipates. They go down the shaft to see how things turned out after the explosion. We follow them with nothing but a helmet with a light, which, in general, is the only weapon that miners carry.

For anyone not familiar with mining, going down the shaft takes more than will power. The ladder feels fragile, it wobbles, and it could break at any time. There are parts where you have to let go of the ladder and hold yourself by your feet and hands, clinging to the rocks along the sides of the shaft.

The walls are clay and wet, and they stain our hands coffee brown. Some of them are “secured” with wood using nothing but the board’s own pressure against the walls. The coligalleros put wood along the walls to give themselves some certainty, they say, that the earth doesn’t collapse. They get the wood from trees that are felled in this same mountain range.

Now, we are with Kike and Juan 30 meters underground. The shaft continues another 20 meters downward. There is a dim light that shines down from the surface, and other brighter ones from the flashlights that we have on our heads.

Here, our senses awaken. The air is thicker and breathing seems to require extra effort from the body, much different than normal.

Knelt down in some kind of underground hallway, Kike tells us that he got his love of mining from his father, and his father got it from his grandfather. But this is a pattern he wants to break so that his son doesn’t follow in the same footsteps.

“I don’t ever want my son to come in here,” Kike says, pensively. “I’d rather help them (his son and daughter) study so they never have to live this life. It’s better that way.”

He says that he took two semesters of law, but that he has always been more attracted to mining than to laws. At his home, Kike says, there wasn’t enough money to pay for his studies, nor those of his nine siblings. They all work in mining.

Along the shaft runs a duct that helps ventilate the the deepest part of the hole, where the air becomes thicker. Sometimes they turn it off in order to communicate through it. Alongside it runs the electrical wire. They use electric tools such as drills inside the tunnels.

After spending a few minutes here, we decide to go back up. Exiting was much easier than entering, maybe because we were propelled by our desire to get out.

On the outside, they call us brave for having gone down the shaft. They say that women often fear entering mines. In Abangares, many participate in the final step for processing gold, which is why the Costa Rica government has defined mining as a “family activity.”

***

One of the requirements that miners must comply with is being a member of a cooperative. That’s the only way, according to the law, that mining can be done in Abangares, but the Ministry of the Environment and Energy (Minae) found in 2015 that 67% of them didn’t comply with this obligation.

Some of the miners that we are with are associated with Coopeoro, which has a concession from the government to work in this mine. Others aren’t members, and no one oversees compliance with this requirement. No one makes sure that the mine workers sell the gold to the cooperatives, as they are required to. They say they get a better price if they sell it to people in Las Juntas.

Of the four gold cooperatives in Abangares, only two have legal concessions to explore the mines. It’s not that the others don’t want to. In fact, at Minae’s Geology and Mining office there are at least 10 pending requests for concessions. According to the same institution, however, “there are no areas available to allocate.”

The current concessionaires (physical persons) who they previously granted land licenses to, don’t want to give their land to the state despite the fact that they are no longer fulfilling their commitment to extract the metal. This forced the state to launch legal proceedings in Costa Rican courts in an attempt to recover the licensed areas.

Conflicts among the coligalleros themselves compound the state’s legal conflicts. Between 2014 and 2015, a dispute over mining territory caused confrontations among the miners. There were arrests, seizure of material extracted illegally, and even closure of tunnels.

This sparked an economic crisis for the miners, and the presidency’s Deputy Minister of Political Affairs and Citizen Dialogue intervened in order to articulate inter-institutional actions that provided a solution to the problems, such as temporary economic aid from the government’s Social Aid Institute (IMAS). Despite these efforts, the conflicts and lack of economic opportunities persist.

“There are times when you don’t have full time work here, and you spend 22 days without working,” Diego says. “You start pulling out your hair and trying to figure out what to do. You have to go and sucuchar.”

“Sucuchar,” in mining slang, is the act of entering the works of other miners and stealing their material. While coligalleros have no labor contracts, there are internal codes about whose property is whose and they understand the risks of “sucuchar.”

***

“There are going to be issues with mercury, because they are prohibiting it internationally,” Nino tells us. Of the miners in the shanty, he is the one who talks most about the political and economic issues of mining.

The miners use mercury to separate gold from the other rocky materials that they extracted from the mines. They touch it with their hands and they throw it in the disc harrows where it swims for hours. Then it drains into the ground and mixes into the air.

What Nino says is true. In August 2017, the Minamata Convention on Mercury came into effect (signed by Costa Rica in 2013). It’s a global accord that seeks to reduce and, ideally, eliminate the use of mercury in activities such as mining, since it is considered a substance that affects the stomach, lungs, eyes and respiratory pathways in people. It also critically damages the environment.

Before the country signed the accord, the members of Costa Rica’s 2010-2014 congress reformed the Mining Code so that within eight years – which will be next January – Minae’s Geology and Mining office (DGM) would teach more environmentally friendly practices for processing gold. The government has not upheld its end of the bargain.

From her office in San José, DGM’s director Ileana Boschini tells me in a phone interview that right now the institution is still conducting research on the best alternatives for processing gold.

“Don’t you think you are starting this process late,” I ask her.

“Yes, many years went by. It wasn’t until this administration that there was interest in bringing order to many things, but the resources are very limited,” says Boschini, who has been in the job for two years.

She adds that the institution believes that cyanide is a better alternative for processing gold. “Despite the fact that is a delicate substance to handle, it’s not as dangerous as mercury.”

With mercury, miners recover less than 40 percent of the total gold inside the material, while with cyanide they can recover as much as 90 percent. But in order to use cyanide procedures, special and expensive equipment is required that will be difficult for the cooperatives to purchase.

“They are trying to form a consortium to see if they can build a large cyanide processing plant. If they continue with that spirit, the interest of joining forces to have a single plant could be successful,” Boschini says.

“Is it realistic to think that, by next year, you can change the technique?”

“It all depends on the capital they have,” she says.

***

Kike lives close to the shaft that he works in, literally on the land where his father and grandfather searched for gold. He lives with his wife, Cindy, and their children Brauny and Yubelky.

“What do you want to be when you grow up, Brauny?” I ask.

“Go into the mines!” he says with a wishful smile

His parents chuckle, but Kike intervenes.

“What is it you used to want to do?” he asks, trying to remind him of an old conversation.

Brauny changes his mind.

“Doctor, doctor. I am going to be a doctor,” he says.

Mining is something that Abangares residents learn at a young age. During our journey through the mines we saw at least four kids under 15 years old. Those who are born in the districts of Las Juntas and La Sierra are practically destined to be miners. Ranching, farming, trade and tourism are secondary activities.

In the other districts that make up Abangares, like San Juan and Colorado, working in the fishing or cement industries is more common.

That’s why it’s not strange that Brauny sees mining as a possibility. He is 10 years old and he already helps his dad process the gold.

“They can study, but it’s very difficult for them to not follow in their father’s footsteps. They are always going to go there. But the idea is that they end up in a different line of work.”

While Kike tells us this, Brauny holds a glass of water in one hand and plays with his favorite toy in the other. It’s a miniature rastra that his dad built. Brauny already tries to laugh off his dad’s attempts to change his destiny, the destiny that the majority of men in Abangares share.

Comments