Bertilia hung between life and death while Santa Cruz was ringing in the new year in 2018. Now she tells the story of how her ex-husband left her permanent wounds after an attempted femicide.

Berti’s case is one of the stories of resilience of Guanacaste women that we share in the November 25th No Room for Violence special edition. A case has been open against her attacker for attempted murder for two years.

Like her, many raise their voices by filing reports to break down sociocultural roles and machismo, and look for a way out of their circles of violence.

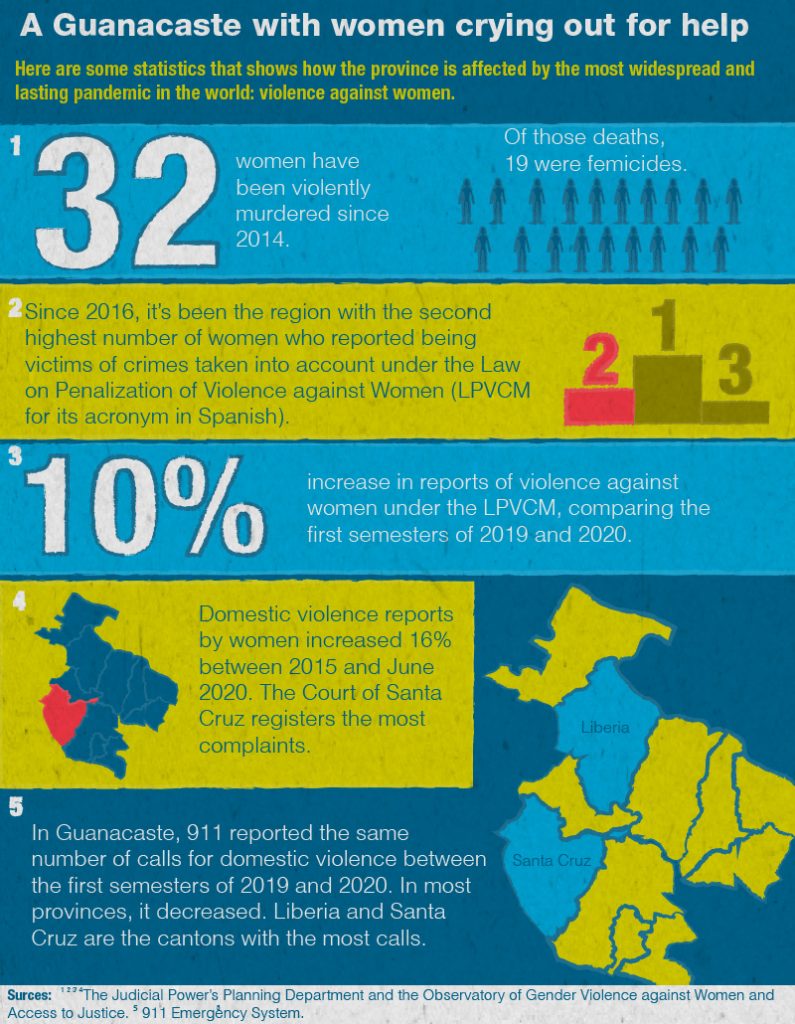

Five statistics demonstrate the bitter pill of femicides, the increase in reports and calls for help from women in the province. At first glance, they’re just numbers, but behind them are the lives of hundreds of women in Guanacaste.

1. A femicidal province

In Guanacaste, 32 women were murdered violently between 2014 and 2020, according to an analysis by The Voice of data from the Judicial Power’s Gender Observatory. Nineteen of these deaths were classified as femicides. In other words, they were killed just because of being women.

However, not all of these femicides were or are being tried as such because the Observatory’s statistics take into account the femicides categoriezed in article 21 of the Law on Penalization of Violence against Women (LPVCM- Ley de Penalización de Violencia contra las Mujeres) and the broader range of femicide established in the Convention of Belém do Pará.

Costa Rica only classifies murders that occur at the hands of the woman’s current spouse or partner as femicide, while the broader range includes those in which there was no marriage or common law union, for example, deaths that occur as the result of a sexual assault, while dating or after a divorce.

Since the broader classification of femicide is not recognized by the country’s legislation, these deaths end up being tried as homicides.

2016 was the year when more women in Guanacaste had their lives taken violently, with 11 murders, of which eight were femicides.

In addition, if we drill down within the province, Santa Cruz is the canton that tops the list with the most femicides. The nine violent deaths of women recorded by the canton in the last seven years were classified in this way.

2. Region ranked second in violence against women

Since 2016, the province occupies second place for the number of women reported being victims of a crime under the LPVCM.

Between the first semester of 2016 and the same period of 2020, the average rate in Guanacaste was 102 complaints filed per 10,000 women, surpassed only by the Southern Zone with 120. Both regions far exceed San Jose, with a rate of 63 complaints per 10,000 women.

The most common crimes in the province are related to “not fulfilling duties,” mainly for violating a protective measure ordered by a judge, such as a restraining order.

“In the different judicial institutions, Guanacaste jumps out there as an alarm that there is more violence against women,” affirmed Jeannette Arias, the Judicial Branch’s Chief Technical Secretary for Gender.

Arias gives workshops on women’s rights and has met with women from the province who were previously trained by the National Institute for Women (INAMU).

She remembers anecdotes of women who say that they were not allowed to manage the farm or the family business and whose parents didn’t want them to inherit it either because that corresponded to the men of the house.

The more patriarchal a place is, the more women are viewed as an object,” she added.

In the end, that objectification leads to more violence. “If [the woman’s body] belongs so much to me, I can attack it psychologically, physically, sexually, simply to satisfy myself,” explained Arias.

3. A pandemic that didn’t extinguish violence

The pandemic didn’t stop violence or the accusations of crimes of violence against women under the LPVCM. During the first half of 2020, Guanacaste registered 10% more complaints compared to the first half of 2019.

In fact, it had the second highest increase of all of the regions in the country, surpassed only by the Southern Zone, where it increased by 11%. This is in contrast with the national trend, which registered a similar number (going from 10,446 to 10,434).

Accusations in the province increased to such an extent that in five years (2016-2020), the province didn’t register as many complaints of violence against women in the first semester as it did this year: a total of 1,291.

“The complaints are undoubtedly increasing because the cases of domestic and gender violence have increased,” said Zeidy Mata, a psychology professional from the National Institute of Women (INAMU) in the Chorotega Region.

During this period of confinement due to the pandemic and unemployment, the women, their sons and daughters spend more time at home with the offender.”, she added.

4. More complaints of violence at home

The number of women who reported being victims of domestic violence in the province increased 16% (757 more) between 2015 and June 2020. During those years, a total of 5,628 women went to court due to violence in their homes.

The increase was highest in the Atlantic Zone, Puntarenas and the Southern Zone of the country. Despite this, Guanacaste remains in second place in filing complaints.

In San Jose, the rate of reporting is 204 for every 10,000 women, but in Guanacaste, the figure rises to 295.

There is no scientific explanation for this behavior in the province, but there are hypothesis to explain it.

At the international level, it is clear that sociocultural and patriarchal roles tend to change more slowly in more rural areas,” explained Arias.

These same roles evolve differently according to each community’s characteristics. Arias explained that more touristy places and beach areas could behave differently from more remote areas because “the environment is much more lax and there is a lot of exchange with other cultures.”

Within the province, the Court of Santa Cruz has the highest number of complaints for domestic violence (with an average rate of 38 per 1,000 women), followed by Nicoya with 34 and Liberia with 30.

5. Calls for help

The pandemic and women living together with their aggressors daily hasn’t kept them from crying out for help. Calls to 911 for domestic violence in the province have remained steady between the first half of 2020 and the same period of 2019, according to 911 Emergency System records.

Data from Puntarenas shows the same trend, but this hasn’t been the case in the other provinces, where calls have decreased instead. In San Jose they even went down by 11%.

“It may be that in more rural areas, the type of employment has required more presence from men, that is, that there are less men working remotely, and that implies that women have the same freedom to call,” pointed out Silvia Mesa, a researcher with the Center of Women’s Studies Research (CIEM- Centro de Investigaciones en Estudios de la Mujer).

“On the other hand, in urban areas where many people work in business, in offices, in public institutions, in those cases, there is remote work, and in those cases, that’s when it’s most complicated,” she added.

Although the 911 Emergency System data is not separated by the victim’s sex, the Judiciary Power’s Gender Observatory estimates that in 80% of the cases in Guanacaste, the victim of domestic violence is a woman.

If we look at the data for the province, Liberia and Santa Cruz are the two cantons in Guanacaste with the highest number of calls, with 255 and 210 respectively. These figures correspond to the average rate per 10,000 inhabitants between 2015 and June 2020.

However, Tilarán went from 41 calls for domestic violence to 911 in 2017 to 92 calls in 2020, which means there was an increase of 124%.

La Voz de Guanacaste carried out this analysis of figures on violence against women in collaboration with the journalist, teacher and data analyst, Hassel Fallas.

Comments