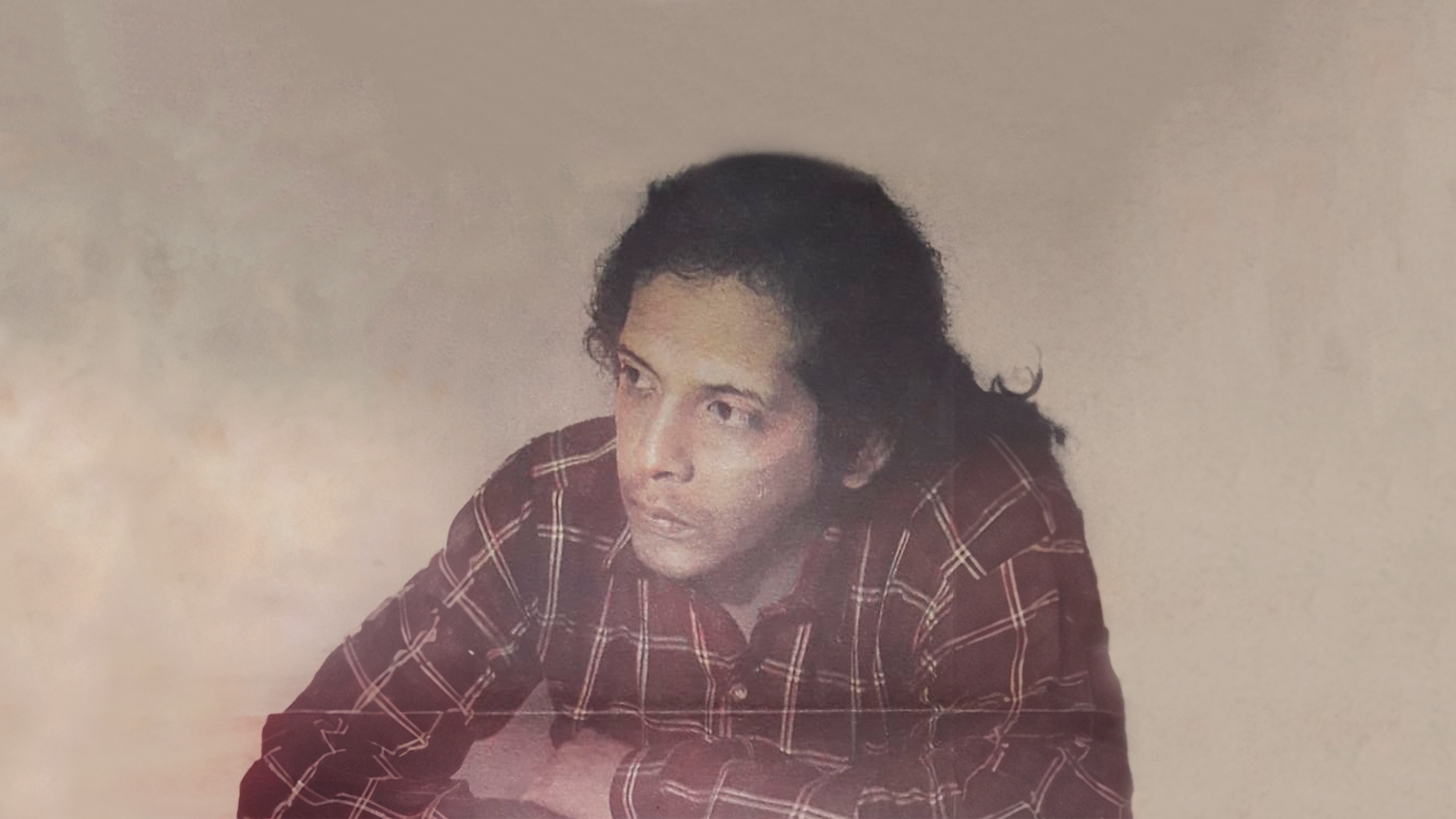

“The most brilliant young narrator, prior to the emergence of the eighties, was Hugo Rivas. He would have been one of the great Costa Rican writers with a little more luck.” This is how novelist, poet and essayist Carlos Cortés Zúñiga describes writer Hugo Rivas Ríos (1954-1992).

His name may not ring a bell with you, but from a small corner in Santa Cruz, Hugo Rivas emerged in the Costa Rican literary world with a journey as fleeting as it was brilliant.

Brilliant because with only three published works – and two awards – he demonstrated the quality of his writing. Fleeting because death overtook him at 38 years of age.

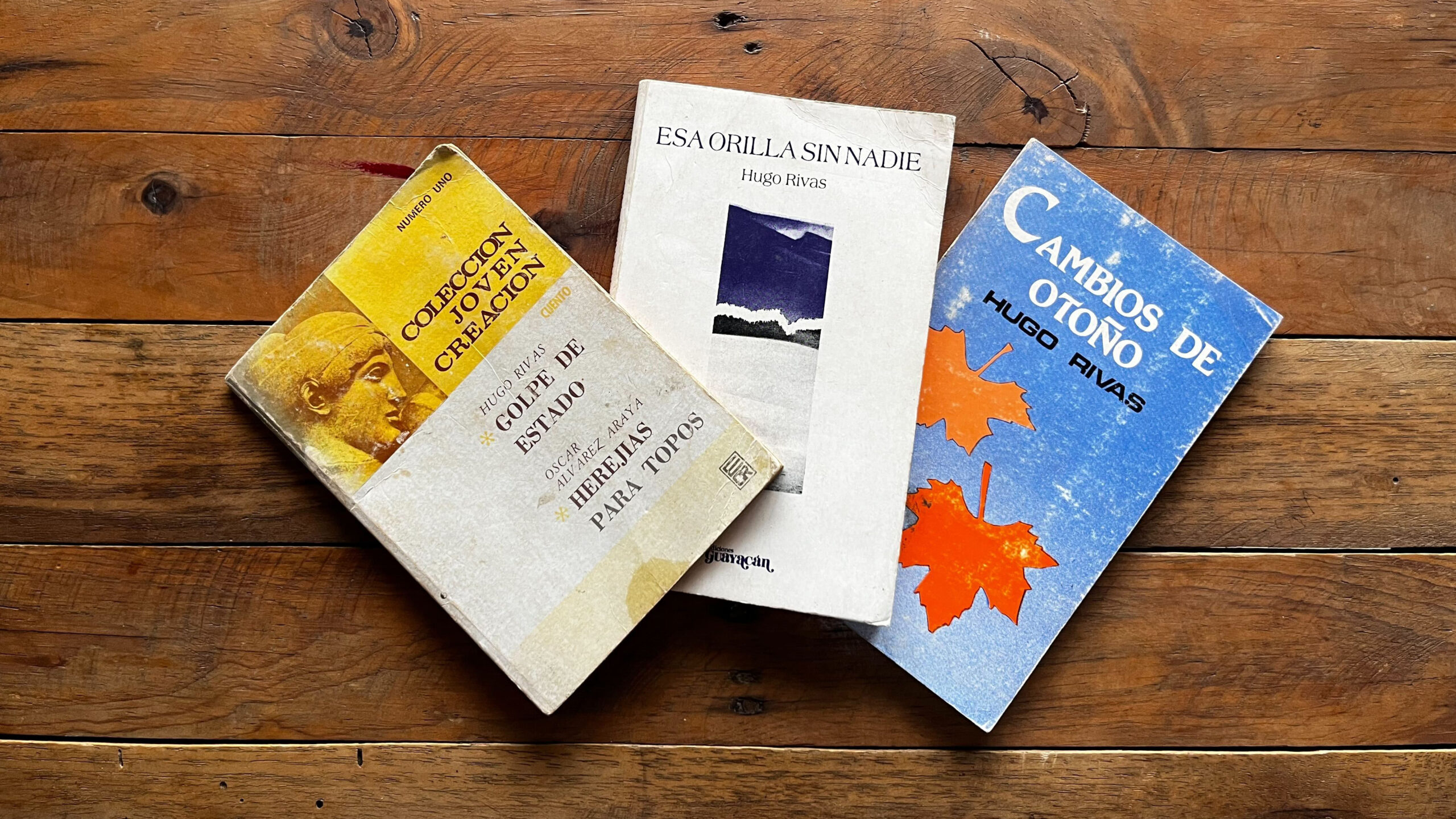

He only managed to publish three of his works: two collections of short stories– Golpe de Estado (Coup d’état) in 1976 and Cambios de otoño (Changes of Autumn) in 1993 – and his only novel, Esa Orilla Sin Nadie (That Shore Without Anyone) in 1988. With his first two published works, he won the Joven Creación (Young Creation) award from Editorial of Costa Rica in 1976 and the Aquileo J. Echeverría award in 1988.

We spoke with family and friends of Hugo Rivas and reviewed newspaper articles to describe his human and literary legacy.

Full of Promising Talent

His younger brother, Alex Rivas, has memories of Hugo scribbling away in 50-page notebooks while still in grade school. “They were a kind of comic strip with drawings and dialogues,” he said.

Hugo had inherited his love for words from his father, Francisco “Chico” Rivas. Chico was an inveterate reader who taught typing to all of his children before finishing school. His mother was Daisy Ríos Guzman.

After attending primary school at Josefina López de Huertas Elementary School and high school at the Liceo of Santa Cruz, Hugo pursued his vocation and began studying philology (the study of language and classic literature) at the University of Costa Rica.

Alex says that he was an introverted person. He spent his time in silence, observing the world around him and mentally developing the ideas that he then captured in his literary works.

“He holed up in the Carlos Monge Alfaro Library to research and then closed himself in his room to write,” he added.

That impetus led him to publish his first book at just 22 years old: the collection of stories Golpe de Estado, for which he won the Joven Creación award in 1976.

Costa Rican writer and chemist Fernando Durán Ayanegui – also former rector of UCR – was a member of the jury for the awards that year. In an article in La Nación in 1993, he expressed the impression that Rivas’s work left on the three members of the jury:

We agreed that we had discovered the work of an extraordinary young narrator. He wrote with a truly enviable experience and ease.”

Text by writer Miguel Fajardo, extracted from an edition of La República (The Republic), in February of 1989.

Setbacks in His Writing

In the same article, Durán confessed that after the award ceremony, he lost track of Hugo and over the years, he came to consider him as one of those writers who, after their first success, dedicate themselves to something else.

But the story was different.

“In 1988, I met him in San Pedro. I had the satisfaction of knowing that I had been wrong, that Hugo had continued creating and had in his backpack at least two books of short stories, one completed novel and two others well on the way,” he said in the column in La Nación.

More than 10 years passed since the publication of the author’s first work until finally the novel Esa orilla sin nadie appeared.

It’s not that it took Hugo all that time to write the book. As Durán told The Voice, the reasons are linked to Editorial Costa Rica.

Hugo had sent the novel to Editorial Costa Rica. And he was very puzzled because it had been sent more than three years ago, almost four,” recalled Durán. “Apparently they had approved it, but he didn’t see any chance of it being published,” said Durán when speaking with The Voice.

Durán believes that the publisher prioritized publications by members of the Board of Directors and friends of those members, showing a notable lack of interest in the needs of the authors.

To writer Carlos Cortés, it was financial problems that plagued Editorial Costa Rica at that time that caused the delay in the publication of numerous works.

Regardless of the story, the work was still tucked away in the publisher’s storehouse, a situation that affected Rivas with his novel, Durán with a story, and Carlos Cortés with an anthology in that same period.

“We helped one another insist. I went with [Hugo Rivas] to the office of Editorial Costa Rica to ask for the manuscripts to be returned to us,” said Durán.

Finally Hugo Rivas was lucky enough to have the independent publishing house Guayacán, directed by Rodrigo Ortiz, publish the novel in 1988.

Political corruption, disorientation and the fruitless search for love and affection are fundamental elements in this work. In it, Hugo uses the technique of fragmentation, breaking down the narrative into parts and exploring in detail the various aspects of the social and personal problems faced by the characters.

The same year it was published, he received the Aquileo J. Echeverría literature prize, awarded by the Government of Costa Rica for creating works that strengthen the Costa Rican cultural environment.

To writer Carlos Cortés, the valuable thing about the work is that it communicates a fragmented vision of Costa Rica that had rarely been seen before.

It was already present in several notable authors such as José León Sánchez and Virgilio Mora. However, none of them managed to approach it with the same clarity as Hugo Rivas did,” he emphasized.

Grief in Guanacaste’s Literature

Rivas died in San José on December 3, 1992 at the age of 38.

His death was discussed several times in newspapers at the time. Columns dedicated to the author share several common themes:

First, they highlight the literary recognition granted to Rivas, considering him a crucial figure for the rejuvenation of Guanacaste’s narrative after 1950.

And secondly, they address the idea that Rivas was not sufficiently recognized during his lifetime, even being a victim of certain meanness on the part of critics and promoters.

This idea is accentuated with the posthumous publication of his short story collection Cambios de otoño, the return to the format that launched his career: short stories.

“I knew about the manuscript a decade before [its publication] and I know that it had already been approved or was about to be approved. Therefore, Cambios de otoño took 10 years in the editorial process,” said Cortés.

For the second time, one of Rivas’ works had to wait several years to see the light of day.

“He had to die, so that a year later, in record time, they edited and published the work,” said journalist and poet Victor Hugo Fernandez in a column published in La Nación in 1993.

Overcoming Obscurity

When comparing Rivas’s situation with classic Costa Rican authors such as Carlos Luis Fallas or Carmen Lyra, whose works have been republished, a significant disparity emerges: None of his works have been republished.

Santiago Porras, a writer from Abangares, reflects on the fate of the author from Santa Cruz in his work “Of books and authors,” emphasizing that Rivas’ premature disappearance deprived him of establishing himself as an international author, a status to be anticipated with his passion and talent for literature .

“Revitalizing the presence of Rivas’s work would not only honor his legacy, but would also ensure that his cultural contribution remains relevant and accessible to future generations,” Porras asserted.

According to the author’s brother, Rivas left some of his manuscripts in the care of his family, who protect them with great wariness.

Perhaps one day, his unpublished works will see the light of day, with the hope of partially correcting the poor luck they had at that time.

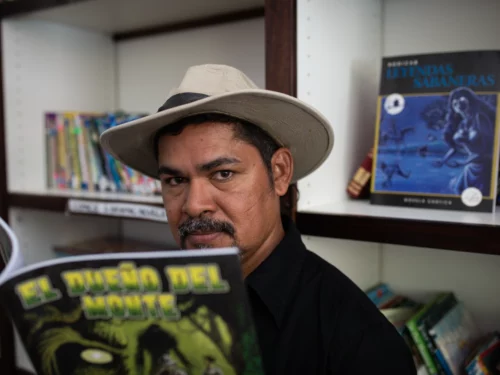

The complete literary universe published by Hugo Rivas.

How to read Hugo’s Writings?

Although Editorial Costa Rica still keeps Rivas’s name as one of its authors on its website, they don’t currently have titles available to buy, as indicated to The Voice.

The suggestion they offered us?

People “can look for books in second-hand stores, even in the National Library.”

Going through different second-hand stores ends up being a somewhat complicated task that requires luck. For now, the most accessible way to read Hugo Rivas is by visiting the country’s public libraries, which according to the website of the National Public Library System (Spanish acronym: Sinalebi), his works are found in 19 of them, and only one rests silently on a shelf in a library in Guanacaste.

Golpe de estado

– Heredia Public Library

– Alajuela Public Library

– Puntarenas Public Library

Esa orilla sin nadie

– National Library

– Desamparados Public Library

Cambios de otoño.

– Heredia Public Library

– Palmares Public Library

– Alajuela Public Library

– San Ramon Public Library

– San Gabriel de Aserrí Public Library

– Cañas Public Library

– Atenas Public Library

– Aserrí Public Library

– Grecia Public Library

– Moravia Public Library

– Naranjo Public Library

– Ciudad Colón Public Library

– Puntarenas Public Library

– Ciudad Quesada Public Library

Comments