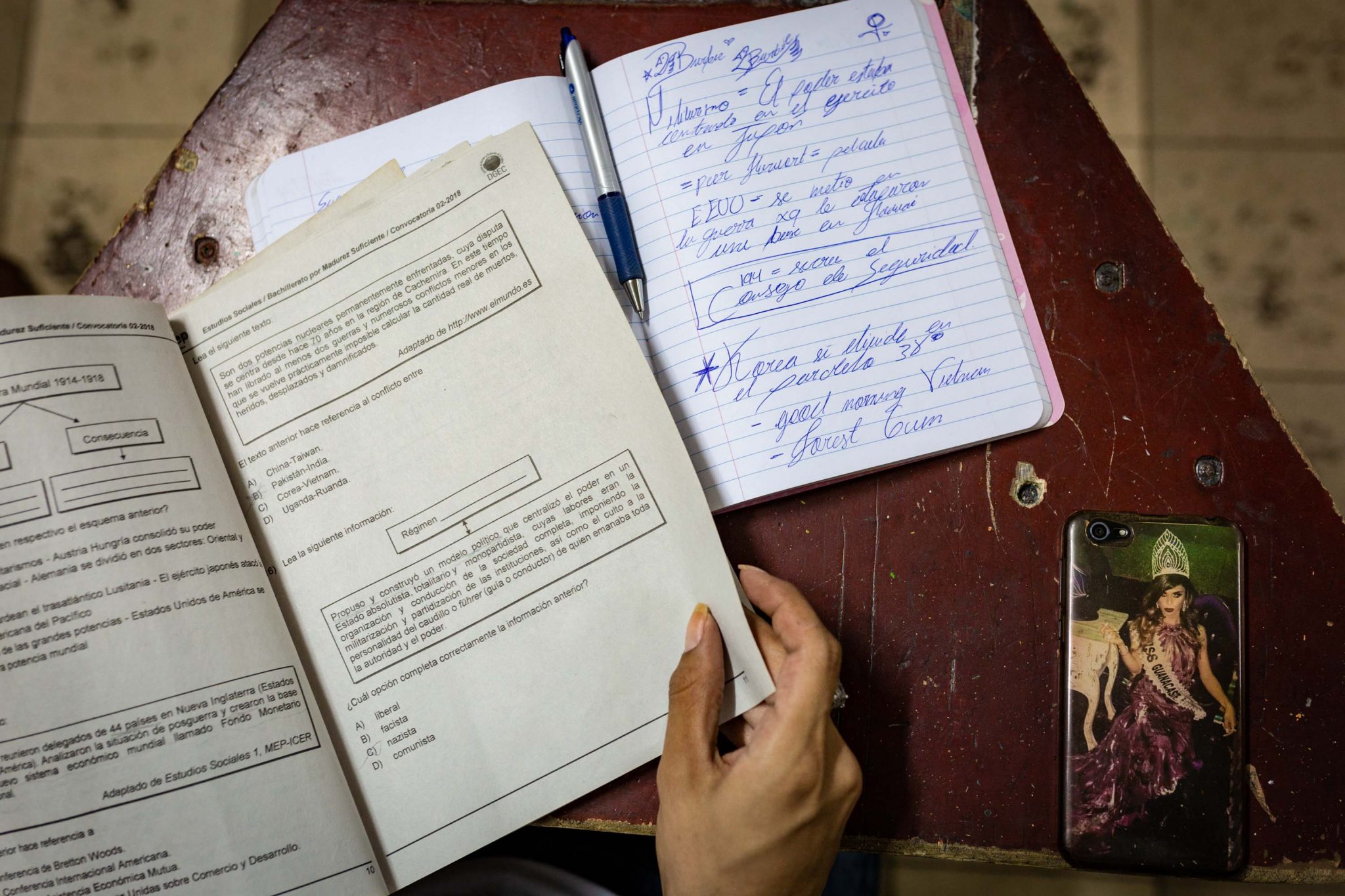

Bárbara and Vanessa walk through the door, cross the classroom and seek out the last row of students to sit down. It’s Tuesday and the clock is nearing 8:30 p.m. in the Moracia School in Liberia, where they are studying their bachelors degrees.

At ages 26 and 40, both transgender women were able to revindicate their right to education, something that evaded them for a long time. They are both studying through a program from the street to the classroom run by the Transvida Foundation and the Public Education Ministry (MEP).

The foundation funds their exams so they don’t drop out because they can’t afford it. They also requested aid from the Mixed Social Aid Institute so they could have extra money that would help them pay for transportation to and from class or buy snacks.

While they and their professors say they feel good, there are images that tell of the challenges they still face. Some people still look at them funny when they walk through the halls and in classrooms. They sit in the back corner and don’t socialize much with their classmates.

Past Obstacles

When she was a child, Vanessa went to a public preschool, but she says she dropped out in third grade when she had to leave her house in Liberia because of violence she suffered at the hands of her father. “He never accepted me. My father mistreated me psychologically and physically. He hit me and he used to say to me that he would make a man out of me,” she says without choking or crying.

When I turned 13, I decided to escape. I was in school and another friend and I went to pick coffee in Naranjo. In the central valley, Vanessa quickly found a job as a sex worker and did that for 15 years.

Like Vanessa, many boys, girls and adolescents experience harassment or bullying because of their gender identity, which makes them to drop out of school. The country doesn’t have data on the number of cases like this one that forced people of the gay, lesbian, bisexual, transexual and intersexual community to quit studying, but stories of trans-women in the country portray this reality.

“We were expelled from the (education) system and we ended up in sex work, negotiating our dignity, our lives, our health,” said the president of Transvida Dayana Hernández a couple of years ago in a piece published by Contexto.

Three Guanacastecan women tell their story of transition and how the name change has changed their lives.

A Range of Possibilities

The alliance between MEP and Transvida started in 2016 at their headquarters in San Jose. Back then, trans girls received classes recognized by the ministry, but at the foundation’s office. They also drafted a guide for teachers for teaching transgenders. That was the beginning of the program “from the street to the classroom.”

The classes at the foundation also include training for transgenders on how to demand respect for their rights, such as access to social security, education and changing their gender on their ID. They also provide them with educational and formal work training.

They opened the office in Guanacaste about two years ago and it’s currently made up of 25 trans women from different towns, according to Barbara, the province coordinator.

What Transvida wants to encourage is being able to finish high school and also promoting a space in public schools where it’s safe to go study,” she says. “It’s an opportunity to get a job and stop relying on the state for education and being forced into prostitution,” she said.

Bárbara still remembers her first steps in joining the LGBTI acivists. She started traveling to the Transvida’s central headquarters in San José to learn about her rights and realized that she had to share that information with the transgender girls in her province.

“I took training in leadership, in how to tell girls what they have to do if they don’t want to pay a voluntary insurance and demand their right to STD tests and all the benefits of hormone therapy. Also about the steps for the ID,” she said.

Getting an Education in the Provinces

After working as a prostitute for 15 years, Vanessa returned to Guanacaste to rebuild her life and started to take night classes, but her mates and professors still stigmatized her because of her identity.

I was bullied so much because they hadn’t yet approved the name and gender identity change and they would call me by the name on my ID. I asked them to call me by my last name, but they wouldn’t do it,” she says.

The name change on IDs makes the girls feel that the state is doing more to defend their rights and in the program from the street to the classroom they feel at home, respected by their classmates and by the school’s staff.

“There are rules and protocols in MEP that are supposed to be used in cases like these, but thank God that when they came we didn’t experience any bullying that we know of because it would have been stopped right away,” says professor Erasmo Chavarría.

“We have never called them by their birth names, but by the names they prefer. What we want is for people to advance.”

The school system’s openness to include them has to do with a series of advances made in the last few years. In 2015, MEP declared itself as a space free of discrimination due to sexual orientation and gender identity and in 2016, when Transvida was founded, the organization started to discuss opening up educational opportunities for the transgender population.

Starting in 2016, MEP began issuing degrees respecting gender identity of students.

The foundation also has alliances with the National Learning Institute (INA) so the girls can take general courses as well as courses designed specifically for them, like human training they receive in conjunction with the National Institute on Womens’ Matters (INAMU). They also recently got the City of Liberia to open up spaces for them in a female entrepreneur program, supported by the local government’s office on women’s’ issues.

“We all have the right to study and the fact that we are physically different doesn’t have to impede our intellectual development. All we want is a lifestyle like any other person,” Bárbara said.

Comments