Still wearing her school uniform, Amanda Zuñiga walked into a meeting in one of the halls of the Guanacaste Museum in Liberia. She was with her cousin, also dressed in her school uniform, and the women gathered there turned to look at them. They were, without a doubt, the youngest at the gathering.

The purpose of the meeting, which took place this year in October, was for people to share experiences and tools to eradicate gender violence. To 17-year-old Amanda, it seemed like a rare opportunity.

For a long time, her father had hit her, her sisters and her mother. And longing to find help, she began to search the internet for information on women’s rights.

She found social networks of feminist women’s collectives or groups in San Jose and other places in the center of the country, but she had never had the opportunity to meet with women in Liberia, where she was born and raised.

So when she learned about a collective in Liberia, Independent Feminists of Liberia, she was surprised.

“It was like wow, [my cousin and I] have never seen a group here in Liberia,” recalled Amanda. They began to follow the group on social networks and found out about the talks. The activity was organized by Acceder, an organization whose goal is to eradicate discrimination based on gender, sexual orientation and identity. For a couple of years, Acceder has increased its activities in coastal provinces.

Since then, Amanda has been interested in joining the collective. “It wasn’t very common to see women’s groups here in Liberia. That is to say, it was more common in other places, like San Jose,” she said.

Between 2021 and 2022, several groups of women in the province have formed new collectives of young feminists. They take to the streets, distribute flyers, set up WhatsApp groups to share with other communities near and far. They accompany their companions to denounce acts of violence and demand assistance in hospitals after sexual assaults. They don’t want there to be even one woman left who doesn’t know and assert her rights.

The newest groups are Samara Empoderada (Samara Empowered) and Colectiva de Tamarindo (Tamarindo Collective). Both were formed after several sexual attacks on women in the country’s coastal areas between the end of last year and the beginning of 2022.

What ended up motivating them to unite was a guide published by the Costa Rican Tourism Institute (ICT), which suggested that women dress “similar to locals to avoid attracting attention” and be “careful with messages that a very friendly or trusting attitude could generate” to avoid aggressions.

“We started because there was a lot of indignation over the sexual attacks that took place in different coastal areas and the ICT’s response at that time, to blame women,” explained the co-founder of the Tamarindo collective, Wendy Valverde.

After the controversy, the ICT eliminated the guides and the government apologized. The head of Tourism at the time, Gustavo Alvarado, acknowledged that they included messages that violated and revictimized women.

The women’s groups from these two coastal communities went out to march for the first time through the streets of their cantons on March 8. It wasn’t the first time that this happened in the province, but before, it only happened in Liberia, or in meetings organized by institutions such as the National Women’s Institute (Spanish acronym: INAMU) or by municipal women’s offices.

Another group that was formed this year was Feministas Independientes de Liberia (Independent Feminists of Liberia). Its objective was to promote a forum that included the canton’s trans women in the March 8th march. Although there were other groups that were planning to march, they had different positions on the inclusion of trans women.

“It’s a group of feminists of different levels and different experiences. They try not to have an absolute position on everything. So the forum is free: free of racism, transphobia, xenophobia and so on,” said Cecilia Sanchez, one of its members.

In Tamarindo, women decided to march for the first time on March 8, 2022. They spoke out against the femicide of Fernanda Quesada and the need for coastal areas to be safer places.Photo: Noelia Esquivel S.

Fed Up with Violence

The origin of these groups in the province is similar to what educator and researcher Laura Chinchilla Alvarado has seen in one of her latest works: the main motivation that calls to women in groups like these is being fed up.

“It’s when they say on an individual level, ‘I’m fed up now with what’s happening to me. They observe that there are others who are fed up [also] with what they’re experiencing, either because they experience it firsthand, or because they see it every day. And they organize,” said Chinchilla.

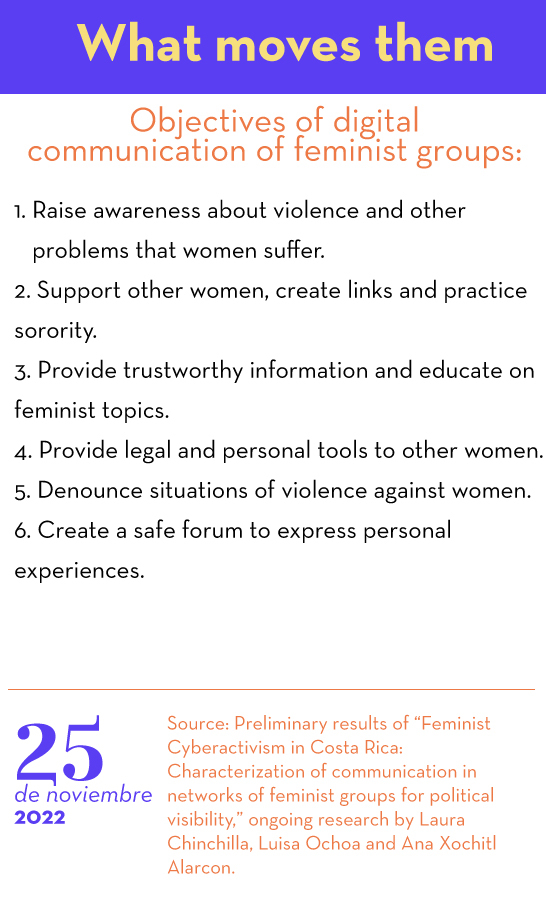

She and two other educators are analyzing the digital communication of 15 feminist groups on social networks. Although they didn’t review groups from Guanacaste, they did investigate others from coastal areas, such as Brujas de la Mar, a local movement from Puntarenas, and other organizations of migrant women in Costa Rica such as Volcánicas.

They found that the main topic they talk about in their posts is gender violence and that their main audience is young women, like Amanda.

These new women’s groups join other more traditional groups. Some meet in community kitchens to build bonds and share their experiences. Others enroll in handicraft, cooking and arts and crafts workshops, where they talk about how to combat gender violence. And there are also groups of trans women, who aren’t always welcome in other places.

Intention, Yes. Time… Maybe

It’s not easy to volunteer time for activism, and it’s challenging for members to commit to remaining active. But Camila Valverde, from the Independent Feminists of Liberia, considers it urgent to do so in rural and coastal communities.

“I could move to San Jose, but really the experiences that happen in San Jose are not the same experiences that happen in Guanacaste,” she said.

There’s an even bigger challenge: calling together women who don’t identify so easily with the feminist struggle or who aren’t reached by communication on social networks.

Virginia DePauli is a member of the group Mujeres Unidas Nosara (Nosara Women United). She says that it’s still difficult for local women from Nosara to become members. The majority are foreigners or women from the Greater Metropolitan Area who have lived in Nosara for years but aren’t originally from there.

“Although we speak the same language, we’re foreigners in a way, so we have to do that groundwork, to be able to fit in, to make them feel trust and that they’re contained in a safe place,” DePauli commented.

The Samara Empoderada group also thinks it’s necessary to include more local women and women of different age ranges. Tatiana Pochet, its co-founder, said that they take it very much into account. They know they can’t limit themselves to online communication, so they hand out flyers to reach older women and people of different socioeconomic backgrounds.

“We always have in mind the women of Matapalo or those of Torito (communities of Samara),” said Pochet. “We say, ‘well, not everyone has a cell phone, so let’s make flyers and walk down the streets,’ because who we want to reach are those who are at home and perhaps don’t know that they’re being victims of violence.”

For all of the women interviewed, the most important thing is to offer information on women’s rights to everyone who needs it. Also, let them know that they aren’t alone, that there are people willing to support them and listen to them. On their social networks, they actively listen to the women who write to them: some seek to vent about situations of violence they are experiencing, others support and advice to get out of cycles of violence.

Diversity

Liberia is one of the cantons with the most groups. That’s where groups such as La Hoguera, the Alza Tu Voz (Raise Your Voice) Association of Women for Rights in Guanacaste, It Happened to Me at UCR Guanacaste (which also integrates experiences of students from Santa Cruz), Mujeres de Tierra Libre and Liberia Independent Feminists have emerged, just to name a few.

Far from seeing it as a division, the groups believe that this diversity is necessary.

“The fight of a black woman is not the same as the fight of a white woman. Both are women. Both have been oppressed, but black women have also been discriminated against because of their skin color,” remarked Raquel, a member of Mujeres de Tierra Libre.

Women in Samara marched for the first time on March 8, 2022. They were outraged by the “revictimizing” guides that the Costa Rican Tourism Institute published to supposedly implement safety practices in tourist communities.Photo: Cesar Arroyo Castro

Researcher Laura Chinchilla agrees that this range of groups is logical and healthy.

“It’s very important here to recognize that we’re not the same. In other words, when we look at communication from a feminist perspective, we understand that if I’m going to develop an organization in a tourist area, with that enormous cultural diversity, it’s not that we’re the same because we are all here,” she cited as an example. “No, we’re not the same, we have different backgrounds, we have and have had different possibilities and opportunities,” she added.

Most activists, regardless of the group they belong to and even their age, know each other and have met in activities organized by INAMU and even by some of the collectives, such as the Alza Tu Voz Association.

It’s precisely in this diversity that they found the fuel to emerge: in the need to create safe forums for all, so that there is not one less, so that more and more young women like Amanda join the fight to demand the end of gender violence.

“Amanda and Dayanara (Amanda’s cousin) arrived at the Acceder meetings on the first day in their school uniforms and came in through the door,” Cecilia Sanchez, from the Independent Feminists of Liberia, recalled about the day of the meeting at the Guanacaste Museum.

“All of us adults already gathered and they walked in like superheros,” she said.

It’s hard for them to measure their achievements, but it’s evident that they’re becoming more visible and that they’re taking significant steps for the well-being of women in their communities. In Tamarindo, for example, the collective created care protocols for victims of violence and has already shared them with district taxi drivers. Their next objective is to distribute them in other businesses such as bars and restaurants.

*César Arroyo Castro collaborated with reporting for this story.

*Raquel is a fictitious name. The woman interviewed wanted to conceal her identity.

Comments