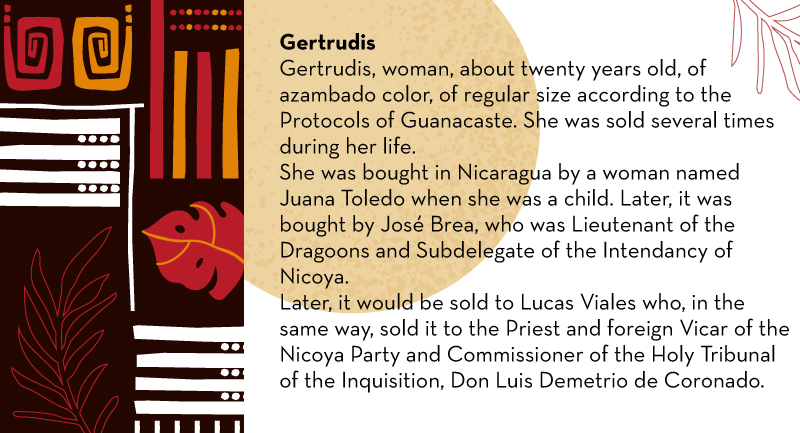

A girl and her mother bought together. A woman listed in a will as the possession of a priest. Black women, “half-breeds,” “browns” or “mulattos” who were enslaved for generations. In some cases, people didn’t even bother to record their names.

These are some of the 15 stories that make up the exhibit “Obituaries from the Memory,” by professor and researcher Daniel Matul. This showing is part of the project “Recovery and Recognition of the Afro-descendant Heritage that the Cantons of Nicoya and Santa Cruz Possess” from the National University of Nicoya (UNA). With it, Matul seeks to contribute to the historical memory of generations of people of African descent in these cantons, so that they have documents that contribute to the enrichment of their identity.

The proposal is to thoroughly review existing documents and Guanacastecan cultural expressions to determine their origin and, with robust documentation, demonstrate cultural expressions of Afro origin, such as the quijongo (a traditional stringed instrument).

An instrument disappeared from the province, and the hope of seeing it again in all its splendor has to do with a seed.

Matul extracted the accounts from the “Guanacaste Protocols,” some historical documents that recorded the purchases and sales, or transfers of goods and properties in the province between the 18th and 19th centuries. Both men and women who were sold were registered in these protocols for decades.

In recognition of International Women’s Day, on March 8, the researcher chose the stories of enslaved women to display on the UNA campus, but little by little, the exhibit began to travel to other places such as the National Library of Costa Rica, the Legislative Assembly and Recaredo Briceño Park in Nicoya.

It’s an effort to recover from obscurity the history of a group of 15 women or historical people who were never recognized. Today, we recognize them, value them and pay homage to them,” said Matul.

African Roots

In July, the National Library of Costa Rica held a virtual conference called “The Afro-descendant in Guanacaste,” headed up by genealogist and philologist Mauricio Meléndez, who reviewed the history of the black population’s immigration to the province during the colonial era.

According to Meléndez, it’s very difficult to know with certainty why the mulatto or Afro-descendant population grew in this region since many historical documents disappeared due to two big fires: one in 1768 in the Mayor’s Office of Nicoya and another in the “convent” or rectory in 1783. Both incidents destroyed more than 200 years of Spanish protocols and sacramental archives.

On December 20, 1911, a Jamaican foreman shot a miner without knowing the chain of events that it would trigger.

Although it could be accounted to a combination of factors, such as: the deaths of the indigenous population due to diseases brought by the Spanish and the increase in the ladino (non-indigenous) population in Nicoya and its surrounding areas starting in 1683, which caused a process of miscegenation of which there are no details but the result is a great change in the ethnic composition.

A study by Meléndez himself shows that in the baptisms carried out in Nicoya between 1784 and 1803, 73.5% of the population was mulatto.

The mulattoes who settled in the areas around Nicoya began to establish small cattle ranches and by the late 1700s, they were already competing with the ranches of Rivas, Nicaragua, in cattle numbers.

Some of these families of mulattoes that were acquiring power, and that had enslaved black people, according to the “Guanacaste Protocols,” were the Briceños and the Viales.

Meléndez affirmed that it’s likely that after centuries of miscegenation, these mulatto people had lost the physical characteristics of their African ancestors, but the socioracial categories of the time continued to identify them as mulattoes.

The genealogist also stated that in the “Guanacaste Protocols” between 1768 and 1821, between 30 and 40 slaves were recorded, and that in 1824, five slaves were freed in Nicoya’s Mayor’s Office.

Confronting the Past

Matul’s main interest is to take the results of the research beyond an academic article, so that it doesn’t remain “kept in a library” and that people can be confronted with their historical past.

During one of the research dissemination activities in Corralillo de Nicoya, Matul recalled that a woman with the last name Viales read the stories of these women and began to cry.

‘She said, ‘this is the history of my family and I ask for forgiveness for everything my family did in relation to slavery. I hope that one day, the Municipality of Nicoya and the State of Costa Rica say sorry for everything that happened, because all those people were wiped off the map,” said the researcher.

Widen the Coordinates

Blackness is still closely linked to the Caribbean side of Costa Rica, where it has 150 years of history, explained Matul. That’s why he considers it vital to expand the coordinates of Afro-descendants in the country.

“We went to the Legislative Assembly to commemorate the Day of the Abolition of Slavery and people wondered, ‘Why are there people from Guanacaste here if they aren’t black; they’re Chorotegas?'” the researcher recalled.

The research that this exhibit comes from seeks to “recover and organize” the province’s African heritage, a puzzle that has lasted more than 400 years. Very soon, Matul hopes to release a second part of the exhibit with the history of enslaved black men, explaining where they came from and telling their stories.

Where to see Obituaries from the Memory?

Place

National Library of Costa Rica

Cost

Free event

Date

August 17 – August 31, 2023

Schedule

Monday to Friday from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Comments