During the final days of October, masks from The Paper House, Michael Myers, Scream, Chucky or a character from the most watched Netflix series of the year show up at celebrations in the province.

That’s why 25 years ago, the government at the time issued a decree to create the Costa Rican Masquerade Day, with the idea of ”recovering and consolidating the cultural identity” of Costa Rica. Or, according to the Ministry of Public Education (MEP), to “counteract festivities foreign to Costa Rican culture.” Bottom line: combat Halloween and all these characters.

On that day, the country celebrates a masquerade that came from the fusion of indigenous and Spanish traditions in different towns of the Central Valley. In fact, in April of 2022, it was declared a national symbol, but what were the masks of the indigenous communities of Guanacaste like, the ones that existed before this blending of cultures?

The Voice of Guanacaste consulted Anayensy Herrera, an archaeologist and co-author of the book Aliento de barro y fuego, la alfarería milenaria de Nicoya (Breath of Clay and Fire, the Ancient Pottery of Nicoya), and anthropologist Pamela Campos to learn more about the masks used by the indigenous peoples of Guanacaste.

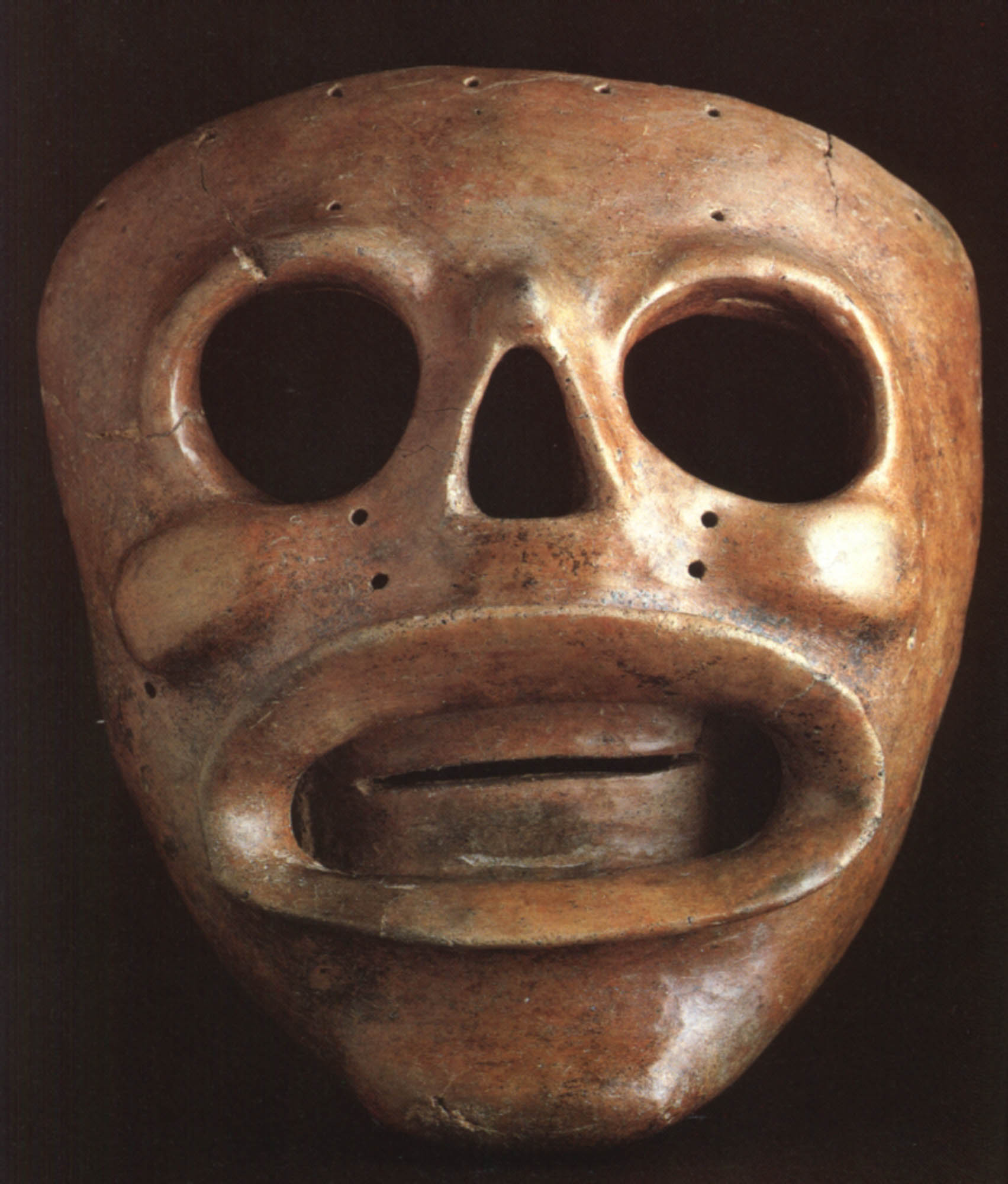

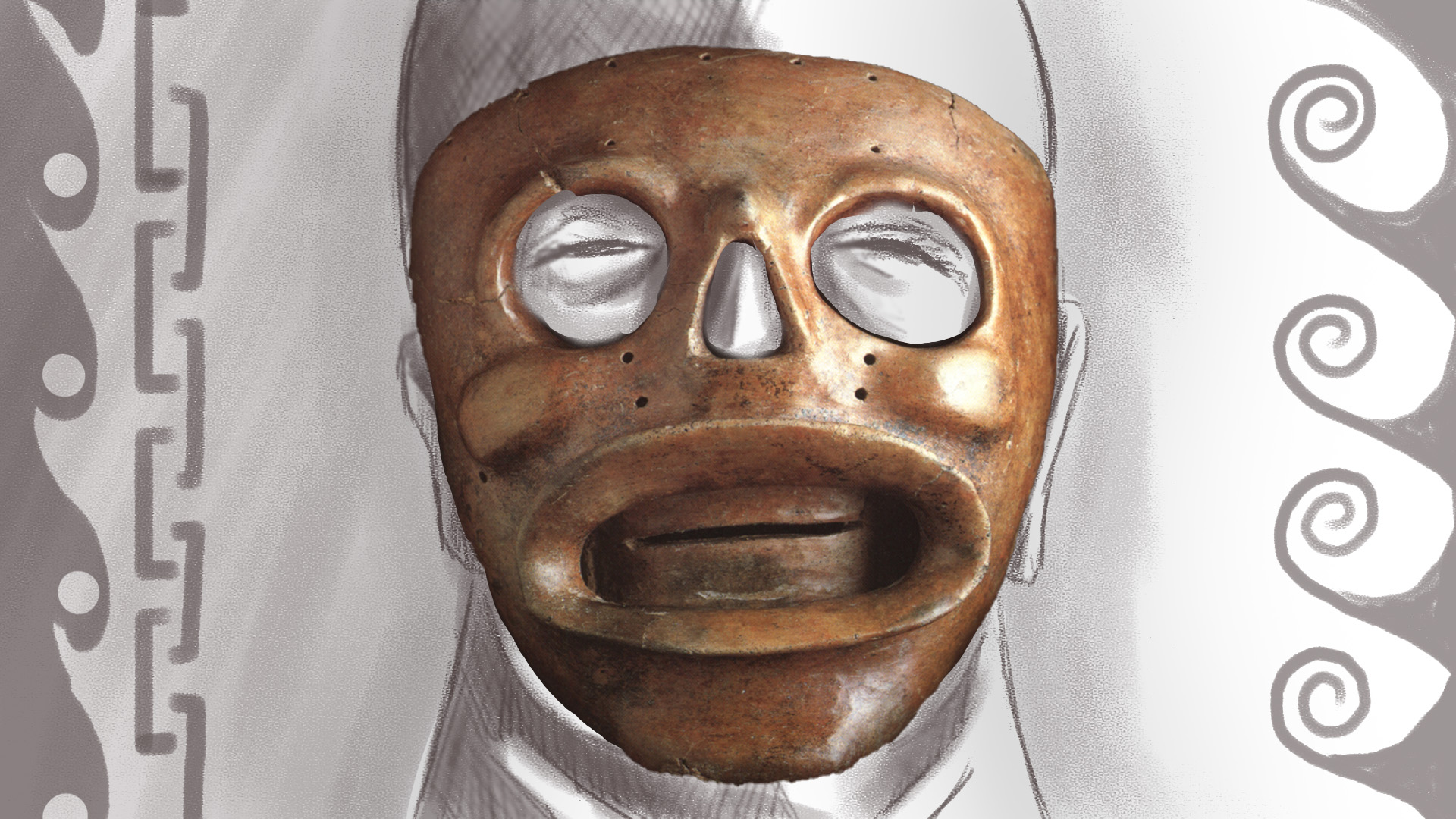

Samara’s Skull

Courtesy: Anayensy Herrera

This piece of pottery was found in Samara and belongs to the Tempisque period, which covers from 500 B.C. until 300 A.D. It’s one of the most studied periods of Costa Rican archaeology, according to the University of Costa Rica’s (UCR) Kerwa repository.

The mask makes reference to a skull due to the lack of eye sockets and the nose. Herrera explained that the small holes on the sides of the mask indicate where it would have been tied. The other holes below the cheeks could have been used to fasten on objects such as beads.

It also could have had pieces made from perishable elements such as wood, which weren’t preserved down to today because the tropical climate decomposes them.

Although it is suspected of being a death mask (which would have been placed on the head of the deceased), it’s impossible to determine that for certain because it was “grave robbed” (looted from an archaeological site).

“How they were used, when they were used and what they represented, archeology can’t answer that because we don’t have the context. [This mask] doesn’t come from an archaeological excavation, but rather from an archaeological looting,” explained the archaeologist.

The book Mascaras, mascaradas y mascareros (Masks, Masquerades and Mask Sellers), by Giselle Chang, explains that when we observe a mask or any other object, exhibited in a museum or in another place out of context, elements are missing to understand, associate and interpret it. That is to say, the object by itself doesn’t tell us everything, since the event in which it was used is essential to understanding it.

A Tempisque Crocodile

Courtesy: Anayensy Herrera

Due to its appearance, this piece could have been made in the Tempisque basin in the Sapoá period between 800 A.D. and 1350 A.D. It’s a vessel with a character that has the body of a man but the head of a crocodile.

According to Herrera, it’s very likely that this piece represented something that really happened. It was used during a religious ceremonial activity in which a shaman used the mask to acquire the traits that characterized the being he was representing.

“There is a character who wears the mask and acts in a ritual, so the vessel is created as a way of representing the courage of that character,” she added.

The Funeral Offering from Culebra Bay

Courtesy: Anayensy Herrera

In Mesoamerica (part of Mexico to Costa Rica), the dead were buried with offerings of jade, gold, and pottery. This figure was discovered in an archaeological excavation in Culebra Bay, but it is originally from the island of Ometepe in Nicaragua. It probably represented an important person so that person would accompany the deceased.

The piece has a large head placed on top of the human figure, has a hat and the mouth of an animal, which could be a crocodile or a jaguar. Due to the shape of its base, it’s possible that it was embedded in an object such as a staff.

“What did it mean? Who did it represent and what value did it have within the culture? I can’t tell you anything at all about that for any of the three,” said the archaeologist, explaining that the existing information on these pieces is “dreadfully scarce.”

Chang’s book states that among most of the indigenous peoples, the custom of making masks was lost as a result of European colonization and the destructuring of indigenous societies and cultures.

One Face to Become Another

These pieces were produced by potters who made utensils for domestic use but also by highly specialized craftsmen.

“The creator is just someone who expresses the values that society recognizes as important,” explained Herrera.

For the archaeologist, the best way to distinguish the masks in some of these pieces is by their anthropomorphic features: a human body with an animal head.

Whoever wears that stops being that person and becomes what he is representing in its head particularly,” she said.

According to Giselle Chang’s book, the mask constitutes a ceremonial object, which the human being uses to identify himself with natural beings such as humans or animals, but also supernatural beings that are significant to his culture.

For all pre-Columbian indigenous groups, the being dwells in the head. That’s why there was a tradition of cutting off heads. When they fought in battles against their enemies, they took them as prisoners and cut off their heads. In that way, they took away their essence.

“If you take away a person’s essence by removing the head, putting on another being’s head then gives you the powers, the value of what that other being means,” added Herrera.

Anthropologist Pamela Campos has researched in depth the use of masks in Costa Rica’s indigenous populations, specifically those of Boruca. According to her, the mask is an object that has two completely opposite functions: to hide us and to display us.

“This need to express ourselves is something very characteristic of human beings, whether it’s being masked, that is, to be others through a mask or rather to visualize ourselves. Putting on a mask to see ourselves, because there’s also that dichotomy of what it means: we are hiding, we are seeing ourselves,” she explained.

According to Anayensy Herrera, it hasn’t yet been possible to determine which culture the potters and artisans who made these pieces belonged to.

Did the person doing this feel very Chorotega or did he feel very Matagalpa, Chontal? That’s what we’re investigating. We still don’t have complete answers,” she concluded.

Today, 25 years after the declaration of Costa Rican Masquerade Day and centuries after we had death masks and shamans with crocodile heads, the same characters that the masquerades sought to combat parade around, such as clowns and TV characters.

Masquerades on San Bartolomé’s Day in Barva, Heredia province.Photo: César Arroyo

That’s why anthropologist Pamela Campos is critical of this type of declaration, since she thinks that it should be accompanied by concrete actions such as incorporating it into school curricula or allocating funds for further research on these types of celebrations.

“The little knowledge that society has about the tradition of the masquerade is due to the fact that sometimes people associate it more with a holiday and not so much with an element that charges you with a super-necessary quota of identity,” she pointed out.

Comments