From Monday to Friday, Carlos Zhou Zheng gets up at around 7:30 a.m. to eat gallo pinto, Chinese noodles or dim sum for breakfast. When he finishes eating, he goes back to his room, which is also his telecommuting workplace. He is a computer engineer, the son of Chinese immigrants, and was born and raised in Liberia.

The LED lights surrounding his workspace and the two screens he works with illuminate him and his collection of old video game consoles, Poké balls and gundam toys.

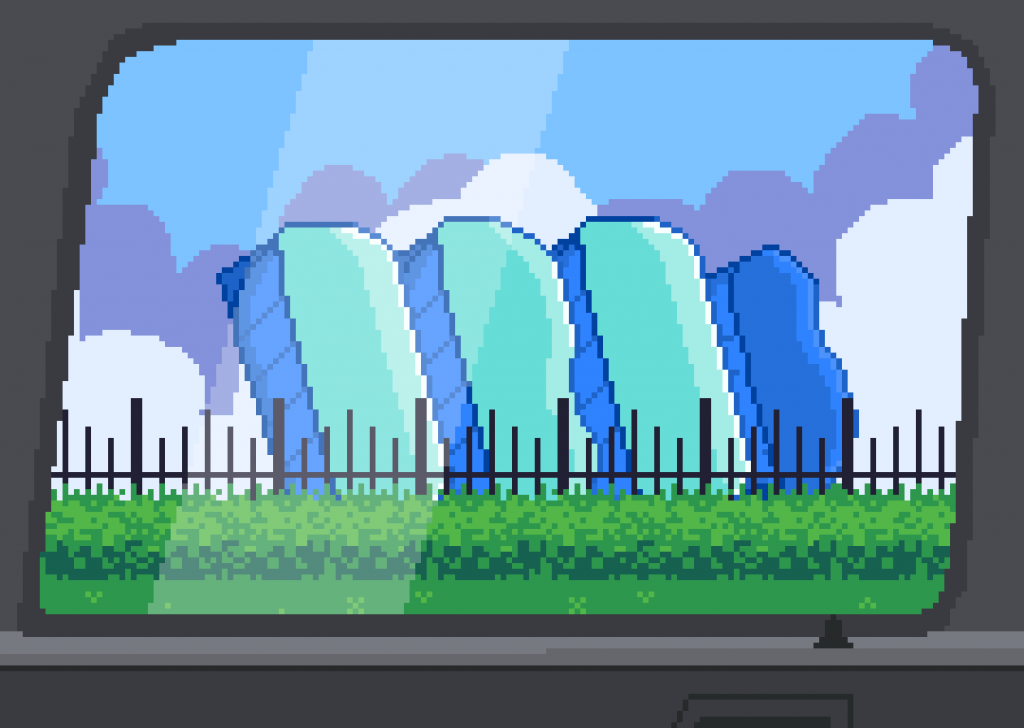

At 5 p.m., he finishes his work as a programmer, and at 8 p.m. in the same room, he creates his digital art pieces. With them, he transforms icons of Costa Rican and Guanacastecan popular culture into versions that seem to come out of those same 2D video game consoles that surround him and marked his childhood.

During the evenings, Carlos draws simplified versions of popular treats, public figures, traditional foods and heritage architecture, picture by picture.

The technique he uses is called pixel art, which is an artistic discipline that uses a computer and graphic image editing programs to create digital art pixel by pixel.

That aesthetic comes from the video games of past decades, when that was the only way to create images with the technology available at the time. Pixel art was recovered many years later by nostalgic people who were fond of the retro style, like Carlos.

“Although I didn’t live when these things like Super Nintendo came out, I had emulators of old games on computers,” said Carlos, trying to explain where that longing for a decade in which he wasn’t born yet comes from.

Painting with Little Squares

He was able to apply that fondness for video games, digital art and programming when he enrolled in a course at the National University (UNA) called 2D Video Games.

I chose to make a game with pixel art and said ‘I’ll see if I introduce Costa Rican things.’ So that’s where I started to draw the ruins of Cartago, the National Theater and the Fortín (a historic guard tower) of Heredia,” he recalled.

He shared it on his personal social networks and people liked it a lot, so he decided to continue creating more pieces of Costa Rican pixel art.

On the huge list of characters and situations that he has managed to ‘pixelate’ are candies, tamales, Juan Santamaria, Milagro the cow and even Edgar Silva, a journalist from Liberia. He has also honored icons from Guanacaste such as the Hermitage of the Agony and the Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Liberia, and the popular drink from Cañas called leche dormida (sleeping milk).

Those “Nintendo version” images that Carlos has created little by little became very popular on his Instagram account dedicated to his illustrations, Colorblind Pixel.

I’ve always been a very outgoing person and I like to do things that people feel they identify with,” confessed Carlos.

According to the Liberian, a key for a piece of pixel art to work well is to simplify what you are drawing without losing its essence, but also “knowing where to put the colors well.”

That specific task is one that he can’t do without a little help.

Colorblind, Asian, Diverse and Guanacastecan

Carlos studied at a Catholic high school in Liberia and during a computer class practice session, he had to draw a priest. While he was coloring the skin, a classmate interrupted him.

- “Mae… What the heck? Why are you drawing this green?

- “What? Green?… Could it be that I’m colorblind?”

When he left school and got home, he ran to take color blindness tests, and he couldn’t see certain colors.

According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, color blindness is a condition in which colors can’t be seen normally. Most people who have color blindness are born with the condition.

His next goal is to study more about video game development to create a game with pixel art aesthetics and a Costa Rican theme. Credit: Cesar Arroyo / Carlos ZhouPhoto: César Arroyo Castro

Carlos remembers this episode with humor because after that, it was never a major impediment for him. Whenever he needs to paint something, he uses the computer’s color selection tools or asks his girlfriend Tamara to help him. He met her while studying at the National University in Heredia.

During those years, in addition to getting together with “Tamy,” as he calls her, he also learned a term that helped him define his gender: non-binary.

Carlos likes cosplay (dressing up as his favorite anime characters) and his girl friends do too. At a pijama party with his girl friends, they suggested that he put on makeup and a wig. He liked it, felt pretty and continues to do so to this day. He created an alter ego named Zhoulina.

“I have never felt that the distinction between men and women is important. I know that there are people who care a lot about that and I respect it, but in my case, I never felt it was important to me,” he explains naturally. Despite defining himself as non-binary, he also uses masculine pronouns.

Among all the things that are part of who he is, is his Guanacastecan identity. Carlos remembers that as a child, he would go to the door of his parents’ clothing and shoe store, in downtown Liberia, to see the Tope de toros (bull parade).

He still has several projects in the works that he plans to dedicate to the city where he grew up, such as drawing the former Comandancia (military headquarters), where the Guanacaste Museum is now located, or interpreting the emblematic Baltodano Briceño House next to Mario Cañas Park. After all, Carlos feels nostalgic for Liberia.

Proof of this is the piece that he dedicated to the “tubs,” as he calls them, which are along the side of Route 27. He sees them every time he returns to Guanacaste.

“When I go on the Pulmitan bus, I see those tubs and I say, ‘I’m going back to Guanacaste. I’m going to my home.’”

Comments