There’s a song that’s always played during celebrations of the Annexation, the Typical Fiestas of Santa Cruz or during town festivals to their patron saints: Puro guanacasteco (Pure Guanacastecan), by German Arredondo.

The lyrics, translated here into English, reveal what gender roles boys are given in the province beginning from when they’re in grade school.

I’m pure Guanacastecan, cowboy and bull rider

I’m pure Guanacastecan, like no one else is better

I’m pure Guanacastecan, a womanizer and a fighter.

Are men from Guanacaste like that? At The Voice, we wanted to know what our readers think, so we raised that question on our Instagram account. The result: a large number of responses ranging from hypocritical, violent, sexist and drinkers to hard-working, brave and loving.

For three decades, Santa Cruz psychologist Marco Vidaurre has provided therapies with a focus on alternative masculinities to men in the province. According to his experience, this Guanacaste macho man profile is formed from the way in which society relates and it originates in the family, which reproduces ideas that come from patriarchy: a global ideological pattern in which men are raised with certain advantages in relation to the female gender.

For example, men enjoy more influence in the political and economic fields, and on a day-to-day basis, they don’t worry about being sexually harassed when they walk down the street.

In addition to these advantages, it also implies assigning them gender roles and initiation rituals to build a hegemonic masculinity, in other words, that set of characteristics that define him as a “real man.”

Getting drunk, putting oneself in risky situations or having to show off a lot of women are rites of initiation in the canton of Santa Cruz, according to a research paper titled “Rituales sociales y procesos de construcción de identidad masculina en jóvenes de Santa Cruz Guanacaste” (Social Rituals and Masculine Identity Building Processes in Young People from Santa Cruz Guanacaste) by psychologists Kristy Barrantes and Sonia Alvarado.

Other rituals of masculinity in Guanacaste have been built around the province’s ranching and hacienda history, explains Vidaurre.

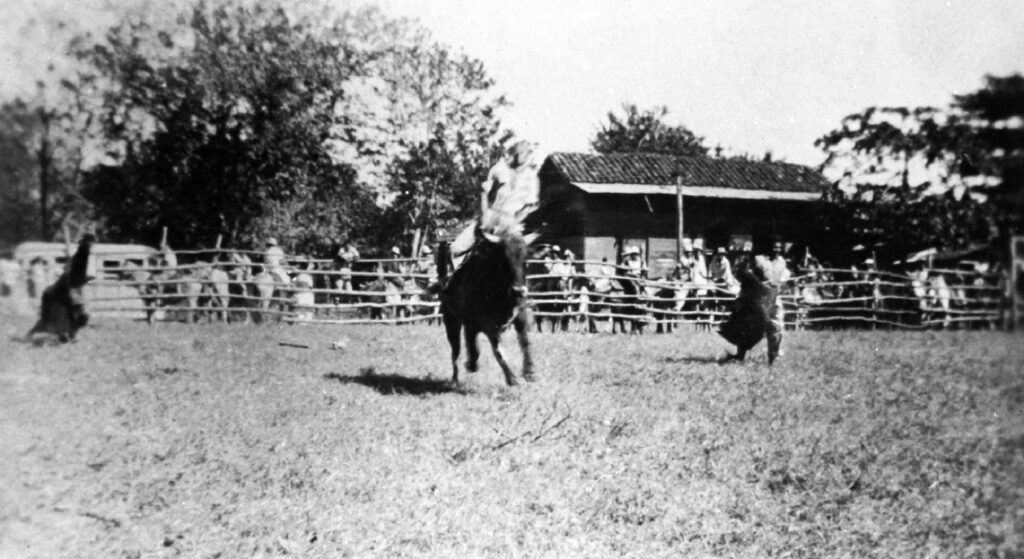

José Cisneros, famous sabanero of Santa Cruz in 1964.Photo: Archivo Nacional de Costa Rica

“I’ve worked with young people since 2007 to the present time, and when we ask what it means to be macho in Guanacaste, all the groups agree that there are five mandates: being a hard worker, being a drunk, being a womanizer, being a fighter and being a bull rider,” describes the psychologist.

And during fiestas, in communities and in families themselves, all these characteristics are reproduced from generation to generation, even rooted in artistic expressions such as the bombas (traditional rhyming limericks with a punchline), retahílas (rhyming verses with word play and improvisation), folkloric dances or songs like Puro Guanacasteco.

“The ideal that must be followed in Guanacaste has to do with the issue of strength, of dominance. Staying on the bull is a form of domination and these people are reinforced, they are given money, statues are made of them. If they die, it’s quite a funeral as heroes,” Vidaurre stresses.

It’s not about eliminating these cultural practices, the psychologist emphasizes, but rather modifying their content to question all of those mandates of society and create alternative masculinities.

A challenge that’s not at all easy, since Vidaurre comments that masculinity was historically constructed from the opposite of what’s feminine. As long as labels exist to distinguish masculine from feminine, possibly for decades or even centuries, these beliefs will continue to be reproduced from generation to generation.

“They have a great impact on the level of forming masculine identity and this really has a very high price on Guanacastecan men,” he emphasizes. And he also reiterates that it’s not that there is more or less machismo in Guanacaste, because that attitude manifests itself with characteristics and manifestations very specific to each region of the country and the world.

Filling the Boots of the Sabaneros

Fulfilling the mandates of what it means to be that macho man, not only in Guanacaste but throughout the entire world, has an enormous psycho-emotional impact on men: they repress emotions and harm themselves by abusing liquor, having unprotected sexual relations with multiple partners, and risking traffic accidents and situations of violence. Statistically, it is men who murder other men and, worldwide, suicides are very high among men compared to women.

Many rituals of masculinity in Guanacaste have been built around the ranching culture in the province.Photo: Cesar Arroyo Castro

In 2022, Costa Rica recorded the highest number of suicides in the last decade: 429 total cases, 347 of which were men. Hojancha appeared among the cantons with the highest suicide mortality rate in the years 2021 and 2022.

Vidaurre affirms that when he has worked in therapy with groups of men, they have generally lived “a horror story of violence” during their childhood.

Unfortunately, parenting patterns are reproduced and they are the ways they learned to do it,” points out the psychologist.

All of these consequences can be worked on by putting into practice alternative masculinities, which allow men to modify harmful activities or situations on a physical and emotional level. Some examples that Vidaurre gave are improving impulse control, equitably assuming domestic chores and expressing emotions.

Men Heal By Talking

When José Morales was studying psychology in San José, he had to go by the Costa Rican Institute of Masculinity, Sexuality and Couples (WEM Institute) and he saw something that caught his attention.

“It looked like a bar. Just guys who were all rough who had mustaches and beards were arriving there and I [thought] ‘ah, how interesting the bunch of guys like that who are going to go talk about emotions in there,’” he recalls.

Once he finished his degree, Morales returned to his hometown, Liberia, and about a year ago he decided to create a proposal similar to the one that he was so curious about.

Daniel subió a la bicicleta (Daniel got on the bicycle) is the forum that he set up so that, once a month, men from Liberia and surrounding areas can express their emotions and interests. Although he prepares some questions to get conversation going, he prefers that the participants be the ones who define the topics discussed in the meetings.

Sometimes we talk for four or five hours straight. We start at seven and finish at almost midnight. So there is a need to talk, we just don’t accept it,” explains Morales.

In the meetings, they talk about different topics such as family problems, suicide attempts or relationship conflicts. It’s a step in the right direction towards a healthier masculinity; Morales affirms that it’s a journey that’s just beginning.

Regarding the responses on social networks to our question about what Guanacastecan men are like, Morales believes that the stereotype “unfortunately, continues to correspond accurately” to the way that a large majority of men in the province exercise masculinity, but he sees certain indications that things can be different.

Contrary to what I believed, for many men close to my age, 28, 29 and under, the image of having to fulfill the role of a ‘Guanacastecan man’ is ceasing to weigh on us,” he comments.

He also recognizes that the fight of feminist women has forced them to work on themselves and look for other ways to exercise their masculinities.

“In the end, we’re pushing for something healthier. It benefits oneself, the couple, those around them, the children. We have to bring it up more between friends; we have to ask ourselves how we are,” Morales emphasizes.

If you have suicidal thoughts, you can call the toll-free line Aquí Estoy (Here I Am), answered by the College of Professionals in Psychology, at 800-AQESTOY (800-2737869) or call 9-1-1 in case of emergencies.

Comments