A generation ago cattle raising in Costa Rica used 50 percent of its farmland but contributed only 20 percent to the value of agricultural production (1). When land is cheap and plentiful but labor is scarce, the cattle industry in Guanacaste made sense. But as land values have increased the business model for cattle raising is becoming less attractive. That, combined with a decrease in annual rainfall, government incentives to reforest pastures and a decline in demand for beef, continue to challenge even the best ranchers.

The Guanacaste cattle industry is less than a century old. Its history captures the essence of the region’s economy today as it moves from agriculture (mostly cattle) to services (mostly tourism and construction).

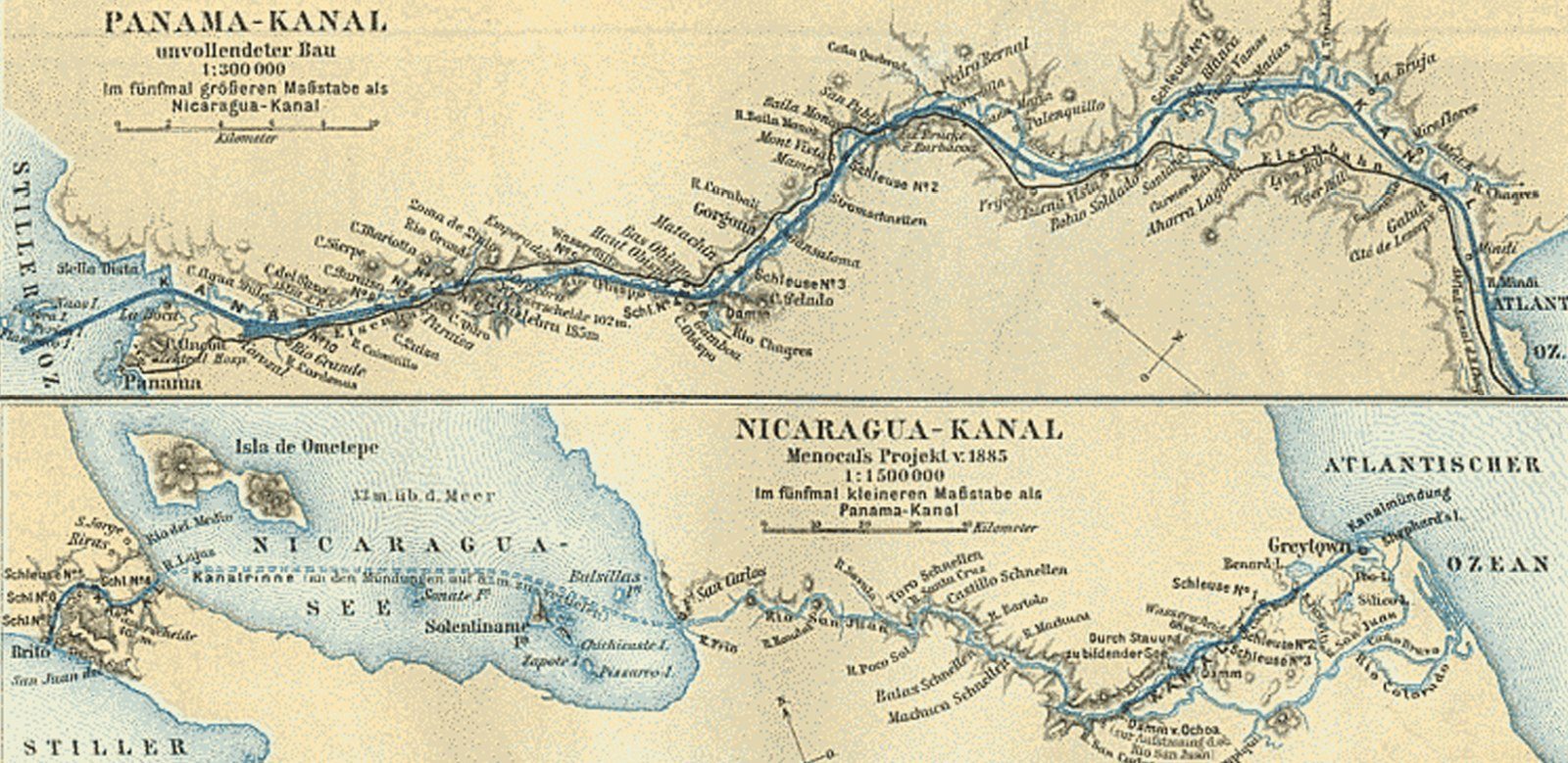

Let’s begin where my last column left off, the inauguration in 1912 of the Puntarenas Line of the Costa Rica Railroad. Before then, the only way to sell Guanacaste beef on the roof for cash was an overland cattle drive across the mountains to San Jose. While some ranchers attempted the journey, it was a very tough way to feed their families.

In Latin America, very large land parcels (+500 hectares) were concessioned to ranchers favored by the government. Those lands without marketable timber (typically termite-proof mahogany and cedar in Guanacaste) often lay fallow and were held mainly for social prestige purposes among San Jose elites (2). The small parcels permitted to be worked by local people (typically under five hectares) were too small to ranch cattle other than for their own subsistence. The cattle rarely entered the marketplace.

Brhamin breeds were first bred in United States from cattle breeds imported from India. Photo by Ariana Crespo

Part of the problem was that the cattle and the natural grasses of Guanacaste were both incompatible to the extreme climate: The grasses did not provide sufficient nutrition for commercial operations. But circumstances dramatically improved with three important innovations: The transport by rail of cattle to San José; the importation of Brahmin breeds and grasses from Africa in the 1920s; and the rise of McDonald’s and other fast food hamburger outlets in the United States.

With competition and the advent of land titling, these large haciendas began to invest in production, importing seed from Colombia to grow jaragua grass (3). The grass originates from Africa, is grown in pastures for grazing and is cut for fodder, including hay and silage and used for both beef cattle and dairy cattle, sheep, and goats. At around the same time, American Brahman cows were introduced in Guanacaste. They were the first beef cattle breed developed in the United States, bred in the early 1900s as a cross of four different cattle breeds from India (4).

Pension Pamera, located in Santa Cruz, was built between 1940 and 1950 to accommodate travelers between Nicoya and Liberia, a structure that takes up almost half a block. Photo by Ariana Crespo.

In Guanacaste, after about 1925, the population grew rapidly with beef exports, mostly centered along the Liberia–Nicoya corridor down to the littoral areas like Tamarindo and Nosara in the rainy season while herds could move in the dry season up to the highlands. But the market for this beef then was strictly San José.

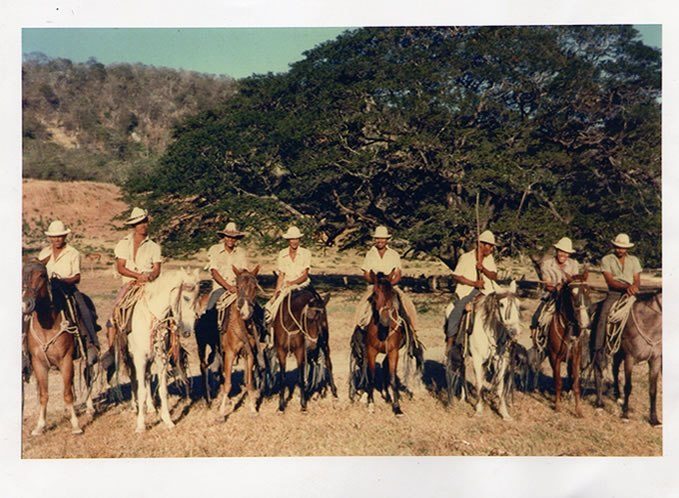

The Guanacaste workforce of 1950 included mostly sabaneros, meaning “savannah men,” tough, machismo cowboy ranch hands. Squatters, rustlers, land thieves and many ranchers with Nicaraguan patrons plus a few “crazy gringos” seemed to be at constant war over land rights, highway robbery and arson, with most of the landscape near the ocean denuded of forests and planted with jaragua grasses that retained more nutrients in an extreme dry climate, fattening cattle faster than the local varieties. In April and May, the sabaneros would burn the fields, protecting the few scattered 50-meter tall Guanacaste trees that provided shelter for the cowboys and cows during rainstorms and shade in the intense heat (5).

Sabaneros in the Palo Verde National Park, Guanacaste, 1969. Photo by Sergio López López.

During the 1930s and the worst years of worldwide Depression, Costas Rica’s leftist politics were strongest in Guanacaste. Many reforms favoring laborers were put into place by the State as the coffee elites and owners of the great haciendas, for the first time, became backbenchers in the National Assembly. Squatters gained additional rights and increasing numbers of small fincas appeared on the landscape.

The next significant change in the Guanacaste economy began in the late 1950s when the fast food hamburger industry expanded from MacDonald’s first entry in California, creating a huge demand for USDA certified grass-fed beef as U.S. cattlemen shifted to higher profit, grain-fed, marbled beef.

Guanacaste became a significant source for ground beef and needs for increasing grazing lands led to still more areas of deforestation. But demand for beef has declined as the problems of maintaining large tracts of land for grazing is no longer the highest and best use for a return on investment.

We are now at a moment when Guanacaste land use is undergoing a full circle change, with pasture land, once forested, is now being reforested either for production of pochote, melina and teak or for carbon sequestration.

Read more of the series “By our will”:

Chapter 1: The Arrival of Gil, The Conquistador, in Guanacaste

Chapter 2: Civilizing the Conquistadors

Chapter 4: Path Between the Seas

Chapter 5: Land of Opportunity

Chapter 6: Nicaragua y Costa Rica

Chapter 7: Celebrating Guanacaste

Chapter 8: The Costa Rican Railroad

References:

1) —Oficina de Planificaci6n del Sector Agropecuario (OPSA) (1979). Programa Agropecuario, Recursos Naturales y Agroindustrial, 1979–1982, San José, quoted in Edelman, M., Extensive Land Use and the Logic of the Latifundio: A Case Study in Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica, Human Ecology, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Jun., 1985), pp. 153-185.

2) Ibid, Edelman.

3) Parsons, J.J., Spread of African Pasture Grasses to the American Tropics, Journal of Range Management, Vol. 25, No. 1 (Jan., 1972), pp. 12-17.

4) Ibid., Parsons.

5) Allen, W., Green Phoenix, (2001), Oxford University Press, Chapter 1.

Rosenbaum has been a researcher and consultant on sustainable tourism and community development for USAID (United States Agency for International Development) and the World Bank in several countries in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. In addition, he has published more than half a dozen books on cultural issues as a senior researcher at George Washington University. Due to his own personal interests – he lived in Nosara and visits Guanacaste often-, Alvin decided to delve into the history of Guanacaste to understand this environment in the best way possible: by incorporating variables from the past into the analysis done going forward, to understand the present and the future of this land that welcomed him with open arms. Alvin spent many hours and several months systematizing all of the information from books and interviews and talking with Guanacastecans who are well-versed in local history to finally produce a series of installments titled “Por Nuestra Voluntad” (By Our Will).

The chapters of the series By Our Will are the author’s opinion and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of this newspaper. If you wish to write an opinion article, contact us at [email protected]

Comments