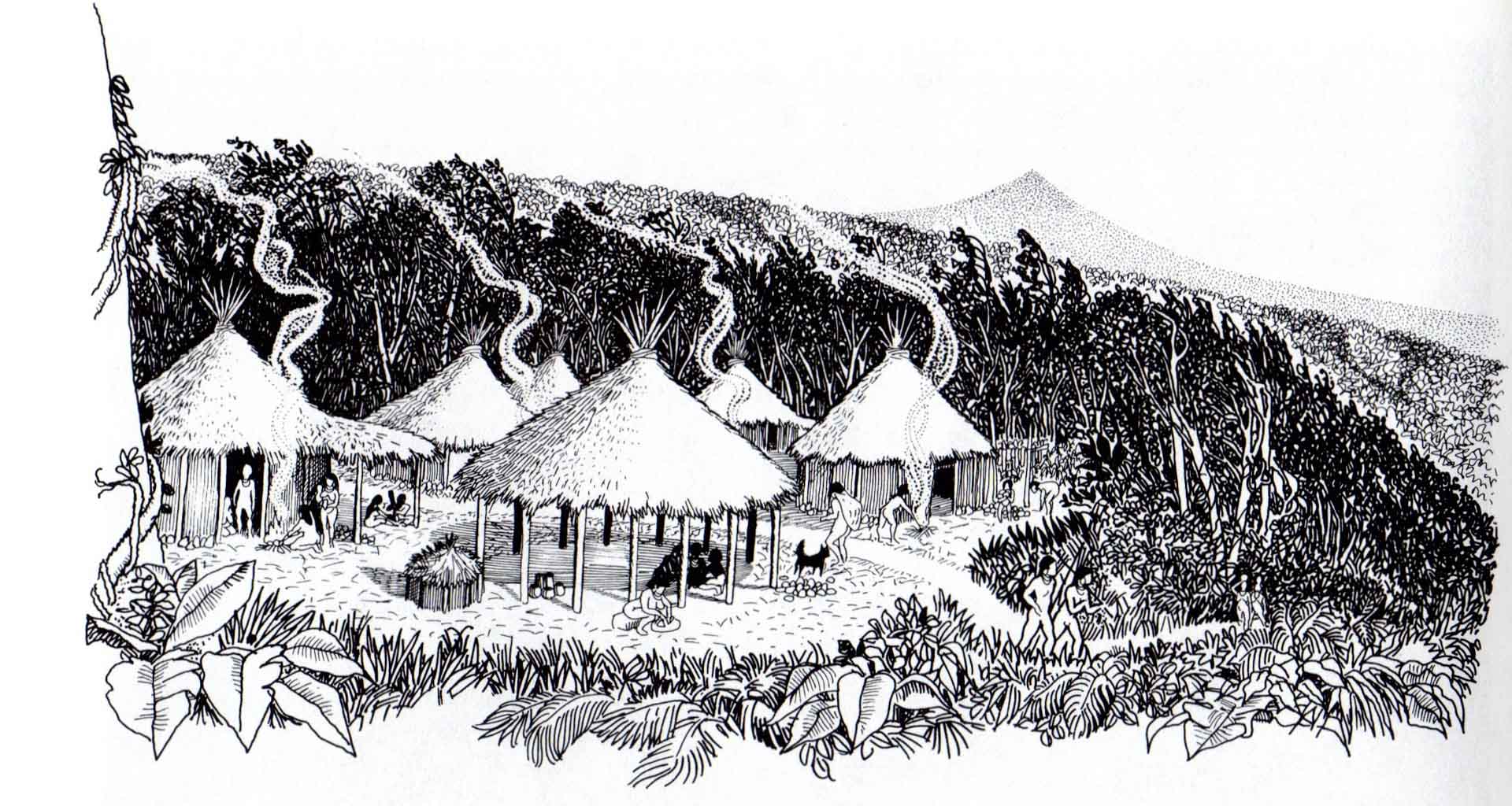

In the distance, you can see Arenal Volcano and next to it, a smaller one called Chato. Smoke rises in thin columns through the thatched roofs of four small huts, built very close to a small, ancient Arenal Lake. Inside these homes, they cook corn in large clay pots with subtle decorations.

Life was something like this 3,800 years ago, give or take, in a small village in Tronadora Vieja, in the Tilarán mountain range. The discovery of these homes represents the oldest record in the country of a “nucleated village,” in other words, a clustered settlement of people living together in the same area.

In the 1980s, anthropologist Payson Sheets led an investigation of archaeological sites around Lake Arenal as part of a job for the University of Colorado, in the United States.

During the project, he and his team identified that this small village existed when they found evidence on the surface: small pieces of pottery or potsherds. It was then that the research team decided to excavate and found the foundations of these ancient structures.

The National Museum of Costa Rica’s Department of Anthropology and History has the reports made by the anthropologist. The Voice spoke with Felipe Solís Del Vecchio, an anthropologist from this department, to find out more details about these first houses.

Our Houses, Our Things

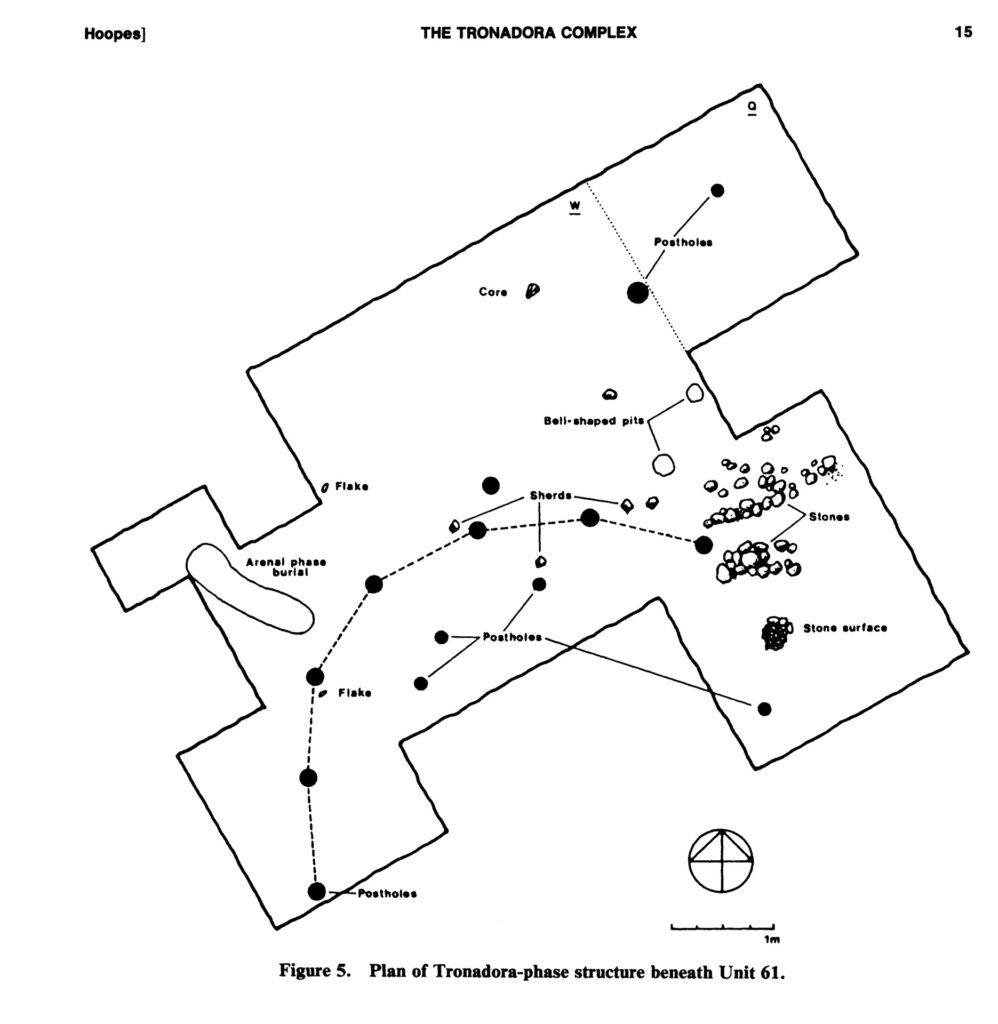

The ground where they excavated is a reddish yellow color. They found some dark circular shapes 15 centimeters (6 inches) wide there that they identified as post molds.

They found four possible houses, five or six meters (16 to 20 feet) in diameter, built with perishable materials, such as reeds, and covered with thatched or palm roofs.

Drawing of the foundation of one of the houses in Tronadora Vieja.Photo: John Hoopes. National Museum of Costa Rica collection.

Through tests such as carbon 14 (used to determine the age of organic materials and some inorganic materials), they concluded that this small village was inhabited around 1800 B.C.

In addition, inside and outside of these houses, they found fire pits and a variety of objects, including ceramics, which they gave the same name as this archaeological site: Tronadora Ceramic Complex.

They are very simple objects that don’t resemble the pieces associated with the Chorotegas. They are large, wide-mouthed vessels that aren’t painted, but are decorated with indentations made by fingernails or stamped with shells.

They also found ears and seeds of corn, stones for cutting and others called “cooking stones.”

People heated the stones in the fire pit and later threw them into pots with water to cook food and so it boiled faster.

According to Solís, in other excavated sites in the country, they have not found these cooking stones, so it could be a distinctive feature of the archaeological sites of that moment in time.

“It was something they were using for cooking that was later abandoned. The issue is that for that time frame, the archaeological sites that have managed to investigate are few. There is still a lack of research,” stated Solís.

The Old Tenants

Who were the people who built and lived in those homes? As the archaeologist explains, they can’t be attributed to any indigenous group for a variety of reasons.

The first is that at that time, there were no chiefdoms or social structures as organized as those that could have existed in the periods closest to the conquest.

As Solís explains, according to different studies, not just archeological but also linguistic and genetic, it’s very possible that these people were related to those who lived in the Central Valley and the southern part of the country, such as indigenous people who spoke Chibchan languages like the Bribris and Cabécar people today.

The Chorotega groups’ migrations from southern Mexico to the Nicoya Peninsula occurred later, between 800 and 900 A.D.

“We’re talking here about occupations from 1800 before Christ. In [what’s now] Guanacaste, there’s a much longer tradition of groups that were not Chorotegas,” explains Solís.

What research into the people who inhabited these houses does show is that they had to leave them for a while.

Arenal volcano and the other now-extinct volcano called Chato buried these first settlements under multiple layers of ash and tephra (solid fragments of volcanic material).

Even so, the same groups repopulated the place a few years after the eruption.

Other Houses, Other Neighborhoods

Round houses, closed in with reeds all around and with conical thatched roofs. That housing structure found in Tronadora Vieja is repeated throughout the country and is a construction system that is still in use. Over the centuries, additions were made to them.

In 300 A.D., some 2,100 years later, houses located in the Tempisque Valley (located between the Guanacaste mountain range and the hills of the Nicoya Peninsula) had clay floors. Researchers suspect that they prepared fire pits at different points on the floors so that the fire would heat the floor and harden the clay.

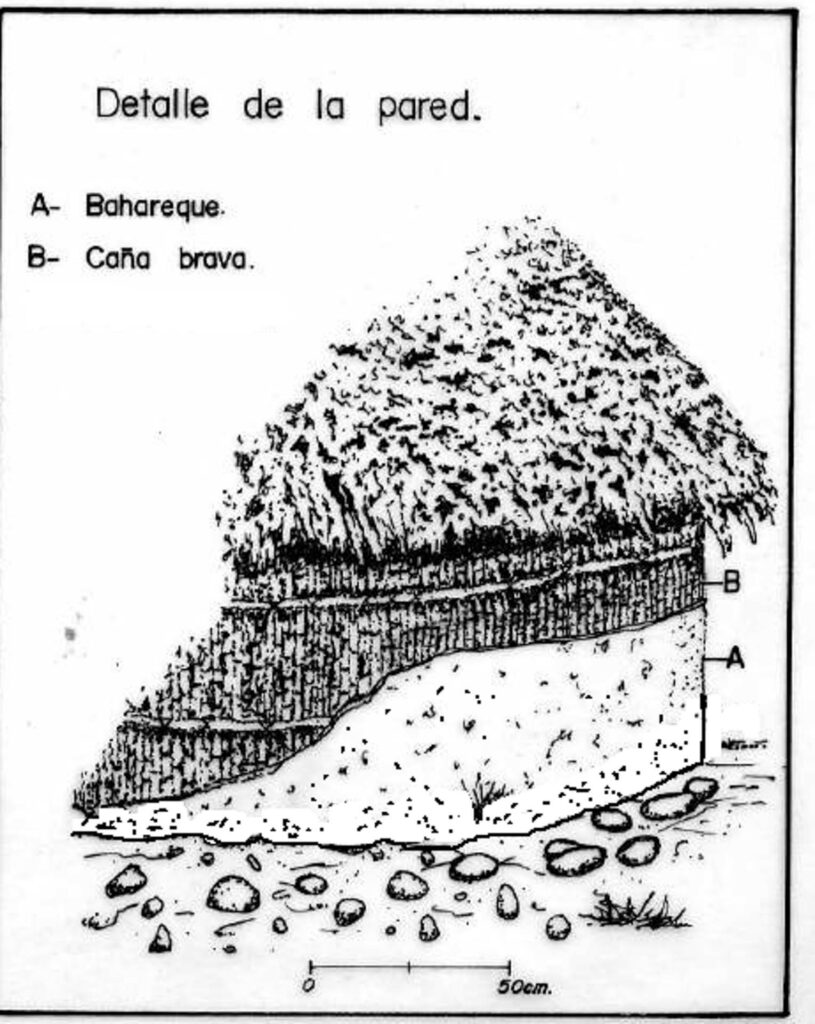

Bahareque floor and wall. La Ceiba Monument. Photo: National Museum of Costa Rica collection.Photo: Photo: National Museum of Costa Rica collection.

Some 500 years later, around 800 A.D. in the Tempisque Valley, they began to build walls in houses. They created a kind of bahareque (like wattle and daub) to plaster the perimeter structure that previously existed made from reeds. Just like with the floor, they probably made small fires next to the wall so that the clay would solidify and not be ruined by rain or other weather factors.

It’s still unclear if this plaster covered the wall to the top, if it bordered the entire perimeter of the structure or only protected the walls that were more exposed to factors such as wind and water.

The reeds and straw covered by this clay decomposed thousands of years ago, but the hardened clay is preserved due to being baked, and impressions of that organic material remained on it. Clay with impressions of reeds. La Ceiba Monument.Photo: National Museum of Costa Rica photo collection.

These walls are still a mystery for the country’s archeology, since some of these clay pieces have remains of what appears to be paint.

“The School of Chemistry at the University of Costa Rica is going to help us determine the nature of that pigment, and see if it is indeed that some of these houses were being painted,” Solís comments.

Idealized representation of a house wall in Jesús María Alajuela.Photo: National Museum of Costa Rica photo collection.

Everyone’s House

Excavation in residential contexts is still deficient, explains Solís, since research is generally focused on cemeteries or other types of archaeological contexts.

Much of the research that archeology produces in the country stems from research that professionals from the National Museum or foreign researchers have proposed. But, as Solís explains, the vast majority of the museum’s knowledge of the location of archaeological sites is due to information from the public.

“Sometimes people know that they have an important archaeological site because they see the structures, they see the mounds, and they don’t get up the courage to call because they think they’re going to take away their property and that’s not true,” explains Solís.

The archaeologist emphasizes the importance of letting them know about these discoveries in time to prevent the destruction of archaeological sites such as cemeteries or pre-Hispanic villages. He also asks people not to move objects before calling the museum, because very valuable information is lost during this extraction.

If you find some object or archaeological site, you can report it to the email antropologia@museocostarica.go.cr or to telephone number 2291-3468.

Comments